Forget soybeans, auto imports, iPhones, crude oil, and cheap Chinese gadgets. Also forget tariffs, duties, and subsidies. Even forget weapons.

The real reason behind the US-China “trade” war has little to do with actual trade, and everything to do with what China’s president, Xi Jinping, said when he visited a memory chip plant in the city of Wuhan in early 2018. In a white lab coat, he made an unexpectedly sentimental remark, comparing a computer chip to a human heart: “No matter how big a person is, he or she can never be strong without a sound and strong heart”.

Because – as we explained last December – what is really at the basis of the ongoing civilizational conflict between the US and China, a feud which many say has gradually devolved into a new cold war if few top politicians are willing to call it for what it is, are China’s ambitions to be a leader in next-generation technology, such as artificial intelligence, which rest on whether or not it can design and manufacture cutting-edge chips, and is why Xi has pledged at least $150 billion to build up the sector. China’s plan has alarmed the US, and chips, or semiconductors, have become the central battlefield in the trade war between the two countries. And it is a battle in which China has a very visible Achilles heel.

But what if the “trade”conflict with China is about more than even technological development? If, as Bank of America assumes, the US-China trade war is about geopolitics and not just economics, the as the bank notes, the “implications for markets are enormous.”

Below are several excerpts from BofA commodity and derivative strategist Francisco Blanch on the true implications of what is shaping up as the biggest civilizational conflict in modern history, which is coming at a time when “America is not as great as it used to be”…

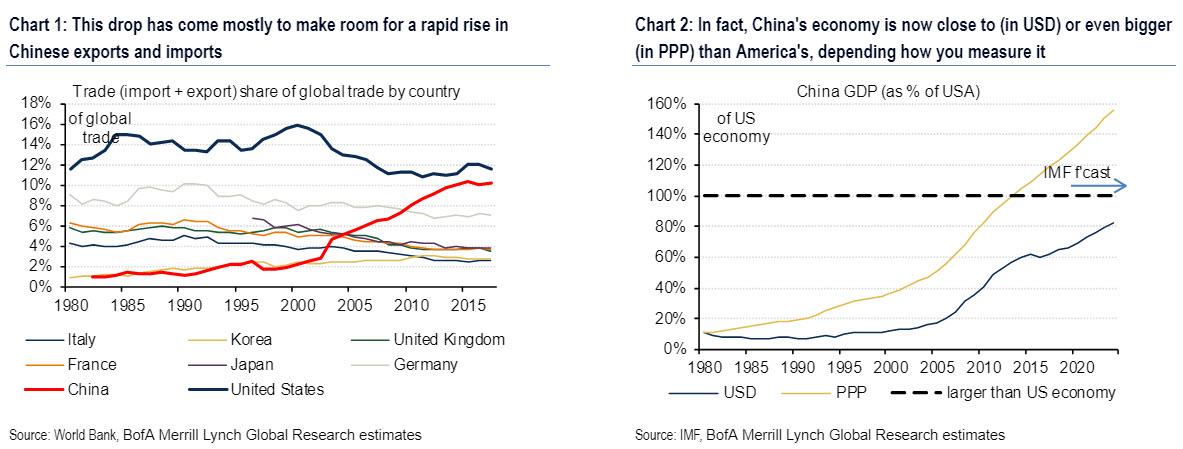

Greatness is a relative concept, measured often against oneself but also against others. In that regard, America has facilitated the rise of China by turning free trade into a global public good. Yet trade theory suggests that hegemons can maximize their income by applying optimal tariffs under certain conditions. The astonishing irruption of China in global commerce following her entry in the WTO has deeply transformed the global economy. For starters, America’s share of global trade has rolled down for two decades to make room for a rapid rise in Chinese exports and imports (Chart 1). Importantly, China’s economy is now close to (in USD) or even bigger (in PPP) than America’s, depending how you measure it (Chart 2).

As Blanch puts it, in economic terms, China is the rising power and the global hegemon is finally starting to feel the heat. As a result, the strategist has taken an in depth look into the issues and found that several historical conflicts between an established and a rising power were preceeded by major trade disputes.

The first key point is that China’s geopolitical ascent and resulting trade conflict, comes as incomes have stagnated in the past decades:

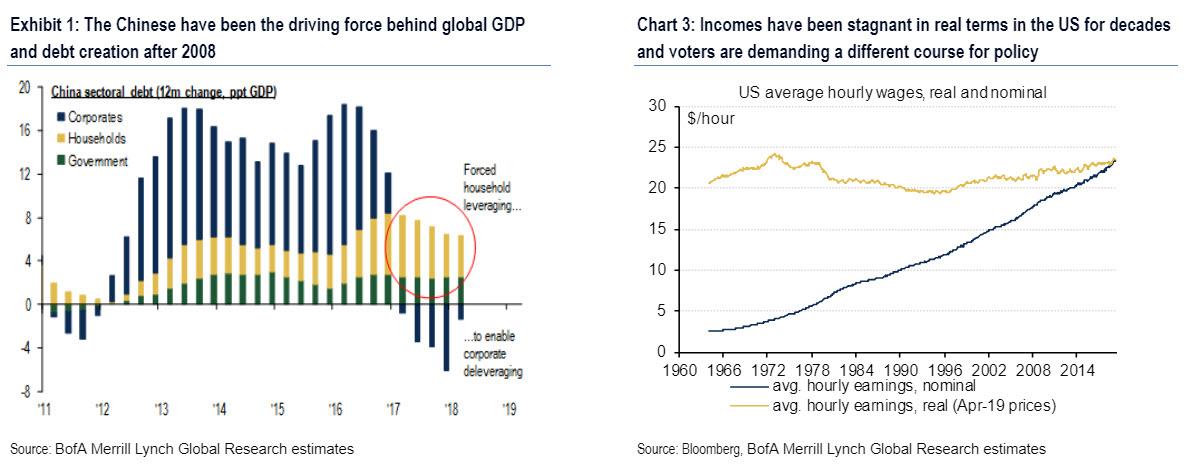

As Blanch notes, it has taken some time, and a major shift in domestic politics, for US foreign and trade policy to catch up with the geopolitical challenges of a rising China. Following the Global Financial Crisis, Washington had too many problems to focus on China’s growth. Plus the Chinese were the driving force behind global GDP and debt creation after 2008 (Exhibit 1) in a world hungry for growth. The European sovereign debt crises of 2011 and 2012 made Chinese economic activity an even more important pillar of the world economy. Neither the US nor other world leaders had the appetite or the domestic support to confront China’s trade practices back then. But now the paradigm has changed. Incomes have been stagnant in real terms in the US for decades and voters are demanding a different course for policy (Chart 3).

In contrast to stagnating US wages, Chinese real incomes and wages have been rising at one of the fastest rates in the world for five decades now. In that sense, Chinese policymakers and business leaders seem to have delivered for their people what democratically elected politicians in the West have not.

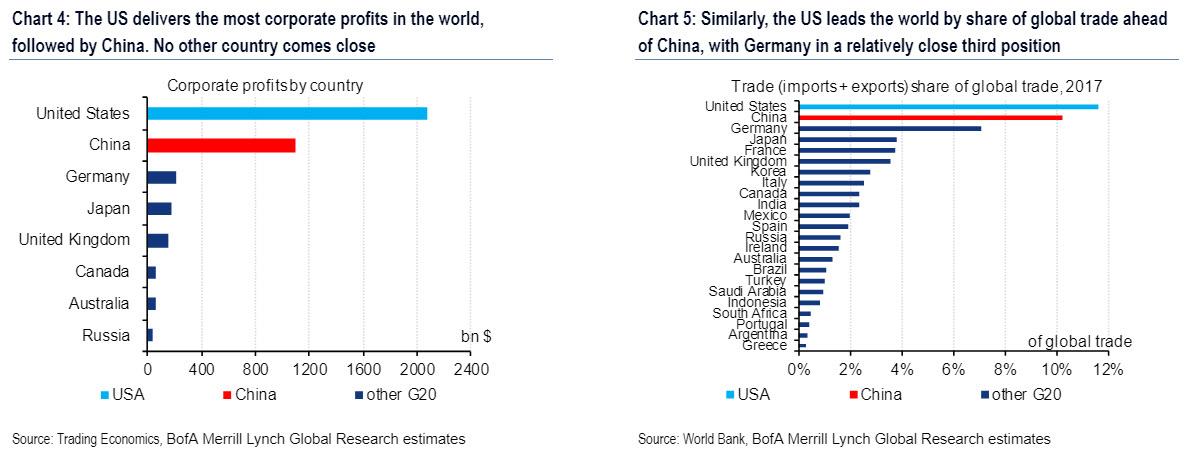

But while the US may have lost the worker prosperity and wage growth title to China, the US still leads the world in trade and profits.

Indeed, America is also experiencing a renaissance of its own at the moment (largely thanks to a fake bull market now well into its 10th year). Buoyant equity markets, the longest economic expansion in history, and the lowest unemployment rate in 48 years have emboldened US policy makers to tackle China. One key issue that has captivated voters is the narrative that American workers’ income is going overseas. This world view largely ignores the effects of technology. But in politics perception is reality. So the ongoing breakdown of global supply chains is just the start of a long trend, in BofA’s view. In any case, America’s economic power is still unmatched. Even if followed by China, the US still produces the vast amount of corporate profits in the world. No other country comes close (Chart 4.). Similarly, as BofA notes, the US leads the world by share of global trade ahead of China, with Germany in a relatively close third position (Chart 5).

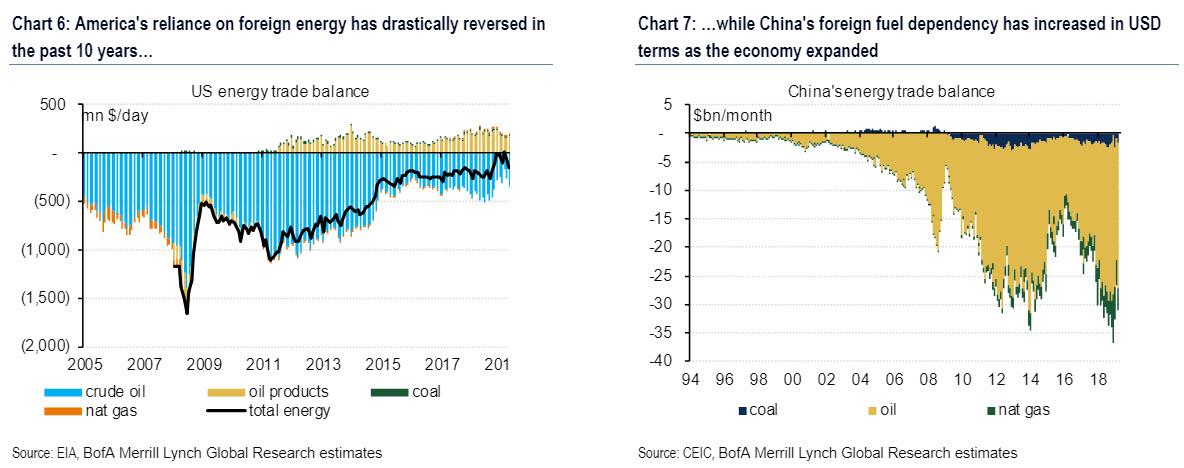

Additionally, last year the US has become energy independent

Discussing the timing of a trade war many have said was long overdue, the BofA strategist writes that “in some ways, President Trump has picked a good time to start his trade battle”: America is in a position of strength and there is bipartisan consensus that China is getting too close for comfort. Another important point to understand is the structure in the foreign trade balances of both China and the US. Energy has been a crucial driver of foreign policy decisions in Washington for a long time. The new angle here is that America’s reliance on foreign energy has drastically reversed in the past ten years (Chart 6), opening the door to a renewed battery of sanctions and tariffs against US foes. Energy independence has also given Washington the confidence that the US economy will be roughly insulated from global oil price swings. Meanwhile, China’s foreign fuel dependency has increased in USD terms as the economy expanded (Chart 7), creating a major Achilles heel for the rising power.

So how did China achieve such fast growth in only a few decades? Simple: as Blanch answers, the biggest driver behind China’s growth was American imports. BofA explains:

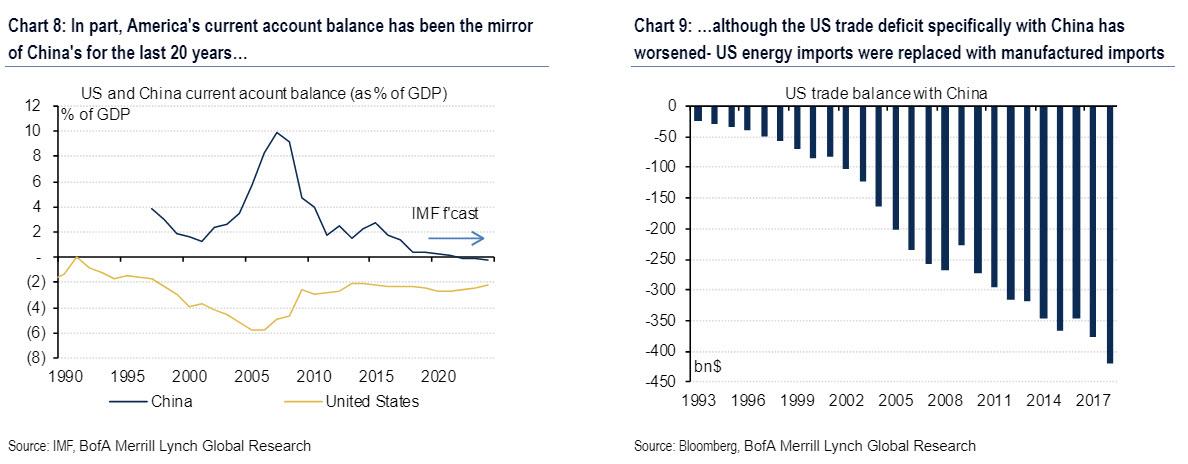

China’s spectacular economic ascendence can be traced to a number of factors. Massive domestic savings and huge capital accumulation, coupled with rapid urbanization and fast rising exports, have all been key drivers of China´s growth. Policy makers in China have also been exceptionally adept at implementing multi decade plans and building infrastructure at a staggering speed. Why is the White House so focused on China? In part, America’s current account balance has been the mirror of China’s for the last 20 years (Chart 8). But even as America has improved its trade balances with the rest of the world helped by an energy renaissance, the annual US trade deficit with China has worsened from 84bn in 2000 to 420bn at present. As such, the drop in US energy imports was replaced with manufactured imports from China in the past decade (Chart 9.).

No one in Washington seemed to notice until voters sent a loud and clear message.

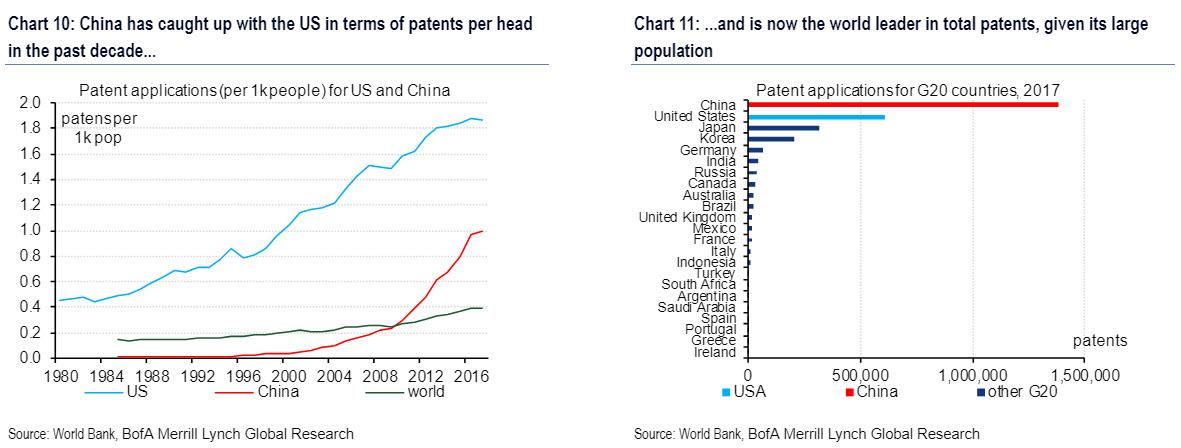

Another reason behind China’s blistering ascendancy was its technology and “intellectual property.” The reason is that for most of its history, China forced foreign companies to transfer technology by setting up Chinese-controlled joint ventures in its domestic market. These rules, coupled with the promise of access to one of the world’s largest domestic markets, encouraged US corporations to transfer technology and turn a blind eye on intellectual property rights violations. Partly as a result of that, BofA notes that China has caught up with the US in terms of patents applications per head in the past decade (Chart 10). And while China is only filing about half the patent applications per head that America delivers, given its population size, China is now the world leader in total patent applications (Chart 11). This extraordinary surge in patent applications, Blanch notes, has surely risen eyebrows in DC.

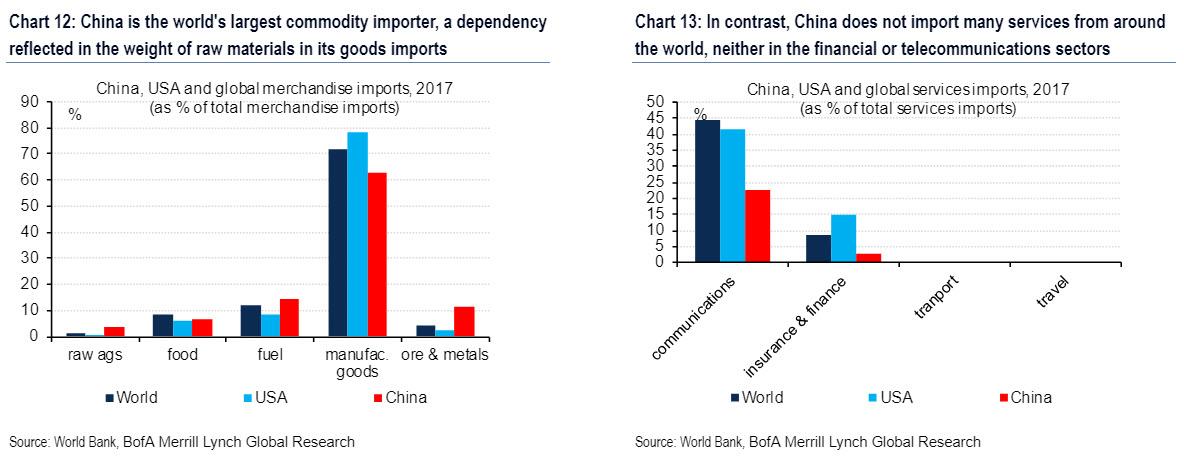

The third key reason for China’s ascent has been its enormous foreign commodity purchases, which is due to its dependency on foreign raw materials. China is the world’s largest commodity importer and this dependency is reflected in the relative weight of raw materials in its goods imports (Chart 12). As BofA notes, China is the world’s largest importer of oil, coal, iron ore, copper and soybeans, and this massive dependency on foreign raw materials “has become a growing weakness. This is particularly true now that China’s strategic competitor has become the largest producer of energy in the world.” In contrast, China does not import many services from around the world, neither in the financial or telecommunications sectors.

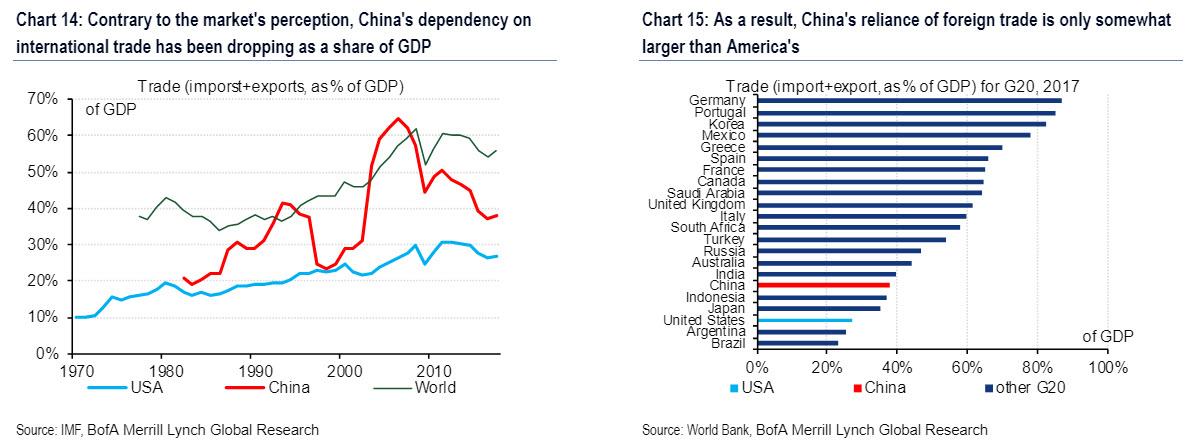

China’s growth has also been boosted on the export side, specifically thanks to a huge surge in manufacturing exports and a very large increase in raw material imports, which has created both a trade partner, but also a major “strategic competitor” to the US. But contrary to the market’s, or at least Trump’s, perception China’s dependency on international trade has been dropping as a share of GDP (Chart 14). And since know that Chinese export growth in the past two decades was very strong, it follows that the falling export dependency is largely the result of China’s GDP growing so quickly. As such, China’s reliance of foreign trade today is only somewhat larger than America’s. Note that the US enjoys one of the lowest foreign trade dependencies as a share of GDP in the G20, only slightly above after Argentina and Brazil (Chart 15).

This means that both the US and China could be labelled large, closed economies in international trade jargon. Germany would be on the opposite end of this spectrum. In practical terms, this relatively low trade dependency suggests that a protracted trade war would not likely have devastating consequences for neither China nor the US. Unlike Germany, both have large, deep domestic markets they can rely upon.

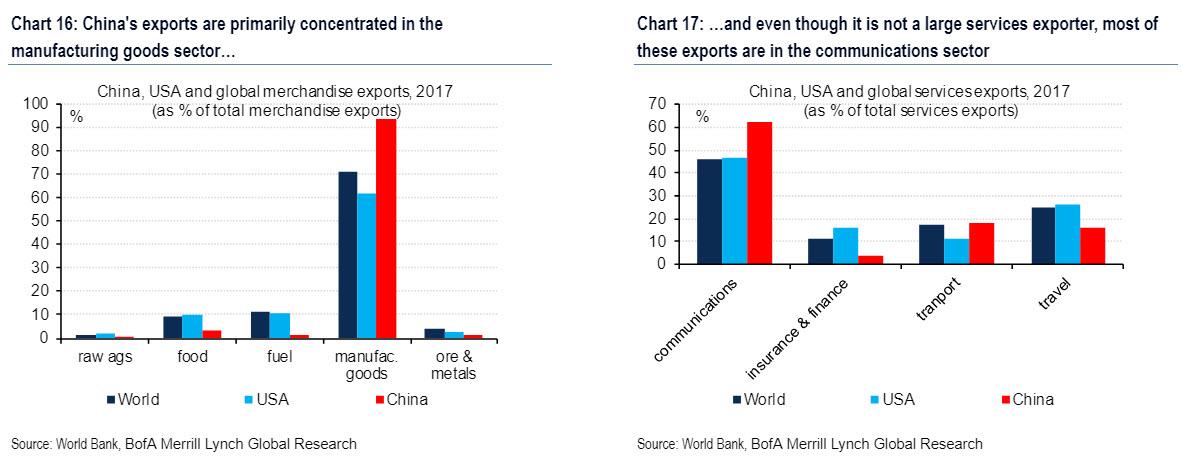

Meanwhile, as China’s global trade standing grew, China’s policies encouraged the rapid development of manufacturing at home (much to Germany’s chagrin). As a result, Chinese exports are primarily concentrated in the manufacturing goods sector (Chart 16). China has been so effective at squeezing out manufacturers that it has ended up in a position of weakness, with limited ability to retaliate against the United States in a trade conflict. This strategic vulnerability is also visible on another angle of the trade war: the telecommunications sector. Even though China is not a large services exporter, most of Chinese services exports originate from the communications sector (Chart 17).

It is therefore not surprising, BofA notes, that the two largest Chinese companies operating in this sector, Huawei and ZTE, have become targets of US government action in recent months. By lifting tariffs on Chinese manufactures and imposing restrictions on the telecommunications sector, the White House has effectively encircled China’s main sources of foreign exchange. The implication is that China’s limited dependency on US goods and services has become a liability, rather than an asset. Now China has limited leverage to retaliate against the US on trade.

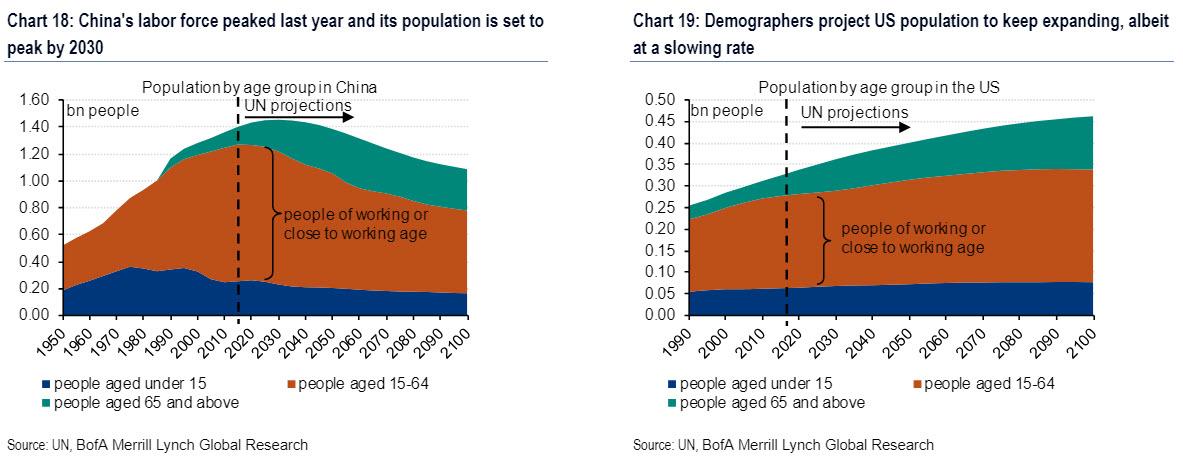

Finally, as BofA recaps the backdrop of the biggest civilizational clash, perhaps in history, demographics are becoming a headwind for China: “Another factor that may have propelled Washington to take a more aggressive trade stance with China now rather than later is demographics. For the most part, working age population is contracting in developed markets and expanding at a healthy pace in emerging markets. In this respect, both the US and China are the exceptions to their respective OECD and non-OECD peers. China’s labor force peaked last year and its population is set to peak by 2030 (Chart 18). In contrast, the aging population problem in Developed Markets is mostly confined to Japan and Europe, while the US actually has still a growing population of working age (Chart 19).”

Why is this important? Simply said, because with diverging demographic trends and a larger economy, “a modest slowdown in the rate of Chinese economic growth could enable the US to retain its title as the world’s largest economy and military spender for decades to come.” Put differently, the faster China turns into Japan, the less of a geopolitical challenge it would pose to the US.

In part 2, we will look at the three other key aspects of the US-China geopolitical conflict: how long will the “trade war” last, what are the likely outcomes, and how will they affect global capital markets.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2VG9VvH Tyler Durden