While it may not yet be the sequel to the GAM Absolute Return Fund or the more recent Neil Woodford investment fiasco, which saw the “investing legend” gate his clients from redeeming money following a serious of terrible investments, the grotesquely named Natixis H20 funds, which we profiled last week as the latest example of how quickly investor panic can escalate once it is discovered how illiquid most fixed income fund investments truly are.

To be sure, the H20 Asset Management fund – yes, the fact that it is named for liquidity when the reason it is about to collapse it that there is none is not lost on us, or anyone else for that matter – refuses to go away quietly and in recent days its parent, troubled French bank Natixis went into crisis-fighting mode to stem a wave of outflows by selling €300 million euros of its unrated private bonds. It then unveiled an ingenious way to halt redemptions without actually imposing gates: according to Bloomberg, it marked down the balance of its holdings “to remove incentives for investors to pull even more.”

You see, when times are great and when funds are happy to demonstrate their performance and portfolios to the world, they tend to “accidentally” mismark their portfolios rather high to appear even more skilled at generating alpha (than they are). However, should the scene flip 180 and the fund finds itself in mortal danger of a redemption avalanche, the first thing the fund’s creative managers do is suddenly reprice all the holdings in the fund sharply lower, forcing those investors who demand their money back to take huge losses.

Truly odd how mark-to-“market” works, when the market for illiquid securities in question does not exist. Perhaps one day regulators will actually look into that.

For now however, we will observe just how successful the anti-H20 fund is in curbing investor enthusiasm to recoup their money, even if they know full well that the longer they wait, the less they will recover.

As Bloomberg explains, the move cut the aggregate market value of the bonds, which were issued by companies linked to German scandal-ridden financier Lars Windhorst, to less than 2% of assets under management, H2O said in a statement on Monday.

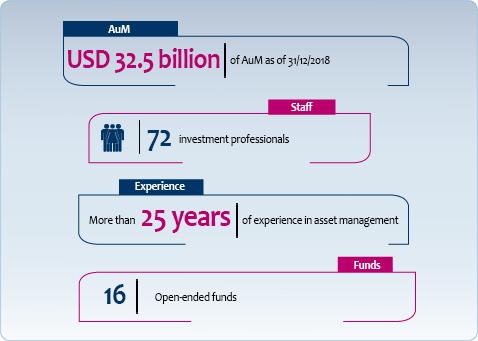

So in an attempt to crush investor enthusiasm to pull money, H2O’s funds, whose assets doubled since 2017 to $37.6 billion before last week’s tumult, will be priced at a discount between 3% and 7% – with the thinking here being that anyone who liquidates will be forced to take a major hit – and the company will remove all entry fees across its funds, it said.

Will this plan work? That’s the question as fund managers hope to reverse outflows from a group of H2O funds that saw their assets drop by 1.1 billion euros on Thursday as analysts questioned their holdings.

By moving swiftly and having fund investors take valuation losses now, H2O is seeking to avoid the fate of famed U.K. stock picker Neil Woodford and Swiss asset manager GAM Holding AG, which both froze funds over the past year amid concerns about whether they’d circumvented investment restrictions. Of course, by admitting just how overvalued its “assets” were until now, it risks accelerating the redemptions as investors in other funds seek to recovery as close to par as possible before they too are steamrolled.

As reported last week, Morningstar questioned the “liquidity and appropriateness” of some of H2O’s corporate-bond holdings as well as potential conflicts of interest, and suspended its recommendation on Wednesday, while research firm Autonomous said the notes are akin to loans, which aren’t permitted.

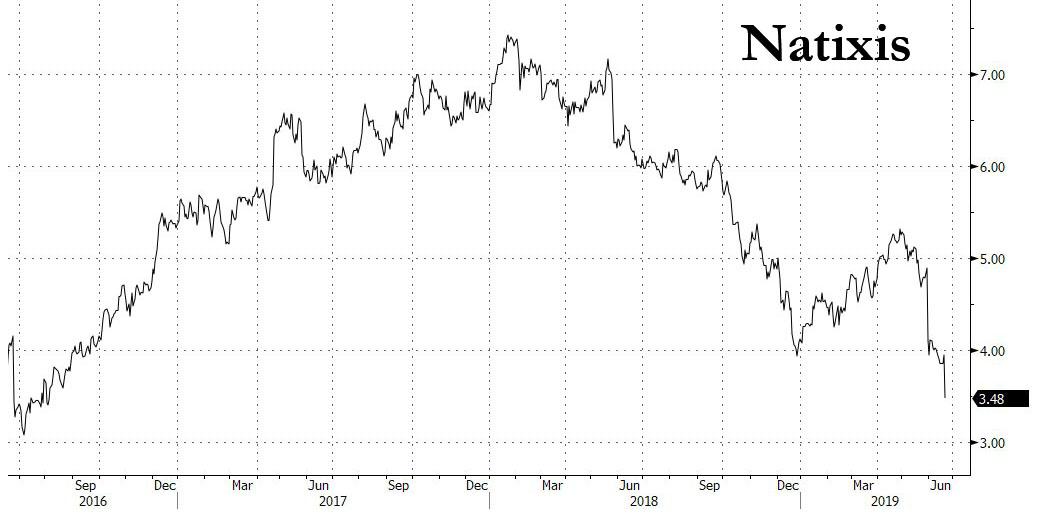

Meanwhile, in an attempt to halt its tumbling stop price, Natixis brought forward a periodic audit of the unit to start June 21. Its shares rose slightly on Monday, halting the two-day slump that followed Morningstar’s move. The bank lost almost 12% last week, falling to the lowest level in nearly three years on Friday.

Additionally, H2O sold about 300 million euros worth of private placements on Friday, according to a letter seen by Bloomberg. The money manager also said it planned to appoint an independent auditor to reassure investors about its investment process and valuation policy regarding non-rated private bonds in their funds, according to the note.

So how did the fund justify the valuation cuts of its illiquid holdings?

According to Bloomberg, the fund said it depreciates all portfolio assets in line with market prices and that it started marking down net asset values as of Wednesday. This is why “our funds have overall posted daily negative performances, despite the good showing of our main investment strategies,” H2O said in the letter. In other words: anything you want to sell will be priced sharply lower.

Separately, a fund spokesman said the aggregated value of the non-corporate bond holdings across H2O’s range of funds was 500 million euros as of Monday, although these numbers tend to magically increase over time.

“The long-term performance drivers of H2O funds, which have been proven over numerous years to the benefit of our clients, remain unaffected as they are not related to this type of investment,” Natixis said in statement on Monday.

“The liquidity of the securities is ensured and will allow it to face potential additional withdrawals” it concluded, although by that point nobody believed it because as has emerged in recent years, starting with Third Avenue and the UK property funds following the Brexit vote, and continuing through GAM, Woodford and now, Natixis, all it takes is for one seller to emerge before everyone else realizes just how illiquid the investments truly are, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of selling which in turn results in more selling, until the fund itself is forced to liquidate at massive losses.

That this is happening in broad daylight and before the eyes of regulators is stunning because this is also a blueprint of how the next crash will play out, not only for bonds but stocks as well, once the overall market goes bidless.

For now, the only questions that have emerged is whether Natixis and other fund managers, most notably Woodford have faced questions over whether they’ve circumvented liquidity restrictions by re-packaging assets. The question now, as we asked last week, is whether the illiquid investments that have caused trouble for H20, GAM and Woodford represent a wider trend in the fund-management industry. Jacob Schmidt, CEO of Schmidt Research Partners, a global investment firm, argues that they are, drumroll, “isolated incidents.” And yes, we are not the only ones to find that an investment firm would argue that all investment firms aren’t liquidity Ponzi schemes.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2LeDbrF Tyler Durden