On August 17, China’s central bank unveiled detailed measures on its long-awaited interest rate reform by establishing a reference rate for new loans issued by banks to help steer corporate borrowing costs lower and support a slowing economy.

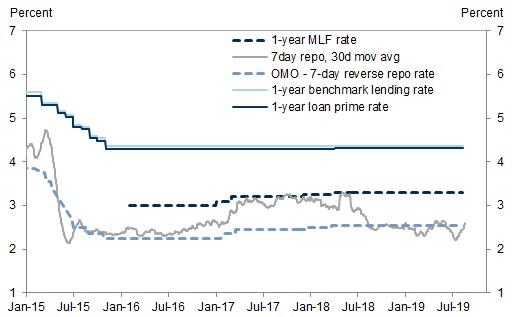

As a key part of the rate overhaul, the Loan Prime Rate will become the new Benchmark Reference Rate to be used by banks for lending which is aimed at supporting funding as well as lower borrowing costs for small businesses; the rate will be set monthly (20th of every month) and will be linked to the Medium-term Lending Facility rate. The current 1 year LPR stands at 4.31% vs. Benchmark Rate 4.35%, with the new LPR set to be published on August 20th, when the National Interbank Center will publish reference interest rates on loans at 9:30 am.

Somewhat similar to Libor, eighteen reference banks are asked to report to the National Interbank Center interest rates based on Open Market Operation rates (mainly MLF rates) with additional premiums before 9 am on the 20th of each month. The National Interbank Center will calculate the arithmetic mean of all reported interest rates after excluding the highest and lowest ones.

As Goldman notes, the new loan prime rate differs from the old one in terms of the following:

- The new LPR is based on open market operation rates, mainly MLF rates, whereas the previous was based on benchmark lending rates.

- In addition to a reference rate for 1-year lending, the reference rates will also include one rate of 5 years or above. Banks will have discretion in loan pricing for maturities of less than 1 year and within 1-5 years.

- Apart from the original ten national quoting banks, eight additional city commercial banks, rural commercial banks, foreign banks and private-owned banks will also be included in the price quotation group. The PBOC explained that newly added banks are the medium and small banks who have relatively large impact on loan markets among peers and who serve SMEs better, which will enhance the representativeness of LPR.

- The new LPR is reported monthly (vs. original daily), to minimize day-to-day rate volatility.

Perhaps more importantly, the PBOC will include the use of reference rates and competitive behavior in the Macro Prudential Assessment (MPA). Furthermore, banks will be required to use the new LPR as benchmark in new loans, while outstanding loans follow the original contracts. And in another similarity to Libor, Chinese banks are prohibited from coordinating to set implicit floors for loan rates, which means that this is precisely what will happen.

* * *

Some further observations: although the new system is supposed to be more market-based, there will still likely be guidance from the central bank. Under the previous system, banks were supposed to be mostly free to set deposit and lending rates, but there were still effective guidance rates from the central bank.

Furthermore, while it is geared toward boosting lending and ushering in lower rates, the new system itself doesn’t guarantee the actual lending rate will be lower. This depends on whether the OMO rates become lower, liquidity conditions and government window guidance. But given the current situation with weak activity growth, heightened trade war risks and a strong desire by the senior leadership to lower rates, Goldman does expect actual lending rates to go down.

These measures form the bulk of planned interest rate reform, though the details are most likely to fine-tuned further in the future. The main apparent leftover task is what to do with existing long-term loans, especially mortgage loans. At the moment these are based on benchmark rate, so implicitly rates will remain unchanged until that rate changes or they are shifted to LPR basis.

Appendix

The following courtesy of Reuters explains how China’s new Loan Prime Rate (LPR), a central part of the reforms, will work.

WHAT IS THE LPR?

The LPR, originally introduced by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) in October 2013, is an interest rate that commercial banks charge their best clients and was intended to better reflect market demand for funds than the benchmark the PBOC sets. However, the LPR’s moves since its launch have generally not reflected those market dynamics with lenders typically reluctant to cut into their profit margins with lower rates and was little-watched by the markets. The one-year rate, for example, is currently just below the benchmark one-year lending rate of 4.35%.

Under the reforms announced on Saturday, the new LPR will be linked to rates set during open market operations, namely the PBOC’s medium-term lending facility (MLF), which is determined by broader financial system demand for central bank liquidity. Setting the LPR slightly higher than MLF rate will in theory give borrowers access to funds at rates that better reflect funding conditions in the banking system, providing a smoother policy transmission mechanism

HOW DOES THE NEW LPR WORK?

The new LPR will be announced at 9:30 a.m. on the 20th of every month, starting this month. The rate has up until now been set using quotations from 10 contributing banks. These banks will be joined by another eight, which include two foreign institutions. Banks will submit their LPR quotations, based on what they have bid for PBOC liquidity in open market operations, to the national interbank funding center before 9am on the day. If the reporting day falls on a weekend or a holiday, the rate will be published on the following working day.

In addition to the existing one-year LPR, the central bank will also use contributing bank quotations to publish similar reference rates for benchmarks of five-years and beyond. Banks will retain discretion as to how they price rates for loans maturities of less than 1-year and within 1-5 years. The LPR will be a reference rate only for new loans issued by banks. Existing loans will still be based on the PBOC-set benchmark rate.

WHY IS PBOC READY REFORMING ITS BENCHMARK NOW?

China has a long history of using two interest rate tracks to drive its lending sector – a market-based rate and a benchmark bank rate. Although China has in recent years given commercial banks more leeway in setting lending rates, the benchmark lending rate remains a key reference for them to price loans, hampering the central bank’s bid to lower corporate funding costs. The PBOC has pledged to “merge” the two tracks and reiterated this commitment several times this year. Beijing has vowed to lower average funding costs for small companies by 1 percentage point this year to spur growth in the economy, amid weak demand domestically and a year-long trade war with the United States.

WHAT ARE THE LIMITATIONS?

The latest move is widely interpreted by the market as an official attempt to revive growth and effectively cut financing costs in the real economy. But some analysts argue that the move could shift commercial banks to become more risk averse in their lending due to growing financial and economic risks.

“We expect the PBOC to have more incentive to lower MLF rates and other quasi-policy rates, but we believe the PBOC’s capability to reduce banks’ lending rates is quite limited due to restraints on credit growth as well as banks’ vulnerability,” said Lu Ting, chief China economist at Nomura in Hong Kong.

“In our view, the PBOC will likely have to walk a tightrope between lowering borrowing costs and maintaining financial stability,” Lu added.

Luo Yunfeng, an analyst at Merchants Securities in Beijing said the impact on corporate borrowing costs will be felt over the long-term and could be far more modest than benchmark rate cuts, which affect both new loans and the outstanding loans.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Investors now await Tuesday’s LPR publication with many market participants expecting the new rate to be cut by 10 to 15 basis points from the current level. Ming Ming, head of fixed income research at CITIC Securities in Beijing, expects the first new rate to be set lower to narrow the yield gap between LPR and interest rate on the MLF, which is now 3.3% for one-year loans. That gap is currently 101 bps.

“If the U.S. Federal Reserve continues to cut its interest rates, chances for lowering MLF to drag down borrowing costs will be relatively high,” he said.

Tommy Xie, head of Greater China research at OCBC Bank in Singapore said the move is a “half step” towards interest rate liberalization, and the link to the medium-term lending rate may only be temporary. “In the longer run, China may also need to loosen the setting of deposit rate,” Xie said.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2HgXlyy Tyler Durden