“One of the things this crisis has taught us,” Peter Navarro, a top administration economic adviser, explained from behind the podium in the White House’s briefing room, “is that we are dangerously overdependent on a global supply chain.”

It was April 2, and, after weeks of largely ignoring COVID-19 as it spread around the world and into the United States, the Trump administration was finally taking the pandemic seriously. That is to say, it was responding in much the same way as it has throughout President Donald Trump’s tenure: by finding new ways to use old laws to expand federal power—particularly power over the free exchange of goods across international borders.

As the novel coronavirus swept the globe and jammed up international supply lines, Navarro was appointed policy coordinator for the White House’s use of the Defense Production Act—a relic of the Korean War era originally intended to allow the federal government to requisition goods to supply the military in a time of crisis. Trump and Navarro have used the law to redirect portions of the economy in an effort to address civilian needs, scrambling markets in the process.

Along the way, they targeted foreign trade too. For Trump, Navarro, and the other neo-nationalists increasingly setting policy for the post-2016 Republican Party, America’s modern problems mostly stem from goods and people coming across the country’s borders. If a problem can’t be blamed on immigration, it probably will get blamed on trade. Sometimes both. And the neo-nationalists weren’t about to let the coronavirus crisis go to waste.

“If we learn anything from this crisis,” Navarro said in April, “it should be: Never again should we have to depend on the rest of the world for essential medicines and countermeasures.”

This framing sounds like simple electoral politics. The Republican Party hopes to use the pandemic as an opportunity to double down on Trump’s “get tough on China” message that helped deliver key Rust Belt states in 2016.

But it’s more than that. Protectionism is now infecting the GOP to a degree that may be difficult to excise when the Trump era ends. Leading Republican lawmakers such as Sens. Josh Hawley (R–Mo.) and Marco Rubio (R–Fla.), who have been cheerleading Trump’s misguided tariff policy for years, are already positioning the coronavirus as an excuse to use federal power to reshape global trade. Even some formerly anti-Trump conservatives have been swayed into backing a nationalist vision of an America that must stand up to China or be swallowed by it. The COVID-19 outbreak has served only to confirm their fears.

“America must never again rely on China for our medical supplies,” Rich Lowry, editor of National Review and author of The Case for Nationalism (Broadside Books), wrote in an early April op-ed for the New York Post. Two weeks later, in an op-ed for The New York Times, Rubio claimed that America was “largely unable to import supplies from China” because China had “monopolized those critical supply chains” for “domestic consumption and their own fight against the virus.”

But this fantasy of a strong America that’s also fully self-sufficient and isolated from global supply chains—and, yes, it is a fantasy—ignores the tremendous benefits that expanded global trade has unleashed in recent decades. Under Trump, that vision was already gaining currency on the right. The pandemic, which originated in China and disrupted global trading, strengthened it further.

The right’s increasingly vocal trade skeptics have taken advantage of a crisis to advocate a national industrial policy designed not only to decouple the United States from the global trading network but to put America on dangerous Cold War–like footing with one of its biggest trade partners. In doing so, they’re pushing ideas that will leave America less prepared for the next pandemic—and have already left us less able to handle this one.

The Fallacy of Chinese Dependence

The argument that the United States ought to be striving for self-sufficiency rests on a story about our dependence on foreign producers for medical equipment, drugs, and other vital products. This is an extension of how Navarro and Trump have cast China as the boogeyman responsible for a broad swath of America’s economic problems. But that story is largely untrue—or at the very least more complicated than it first appears.

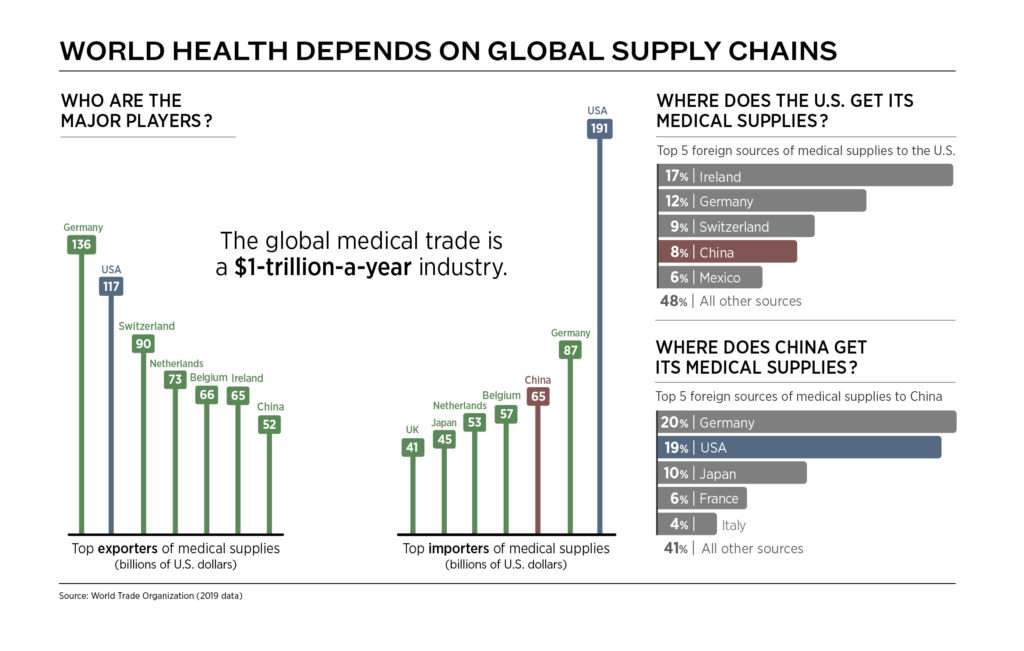

Data from the World Trade Organization (WTO) show that over the past three years—both before and during Trump’s trade war with China—American consumers and businesses imported an average of $13.5 billion per year in medical supplies from China. That’s good enough to put China in fourth place, behind Switzerland ($15.5 billion annually, on average), Germany ($19.6 billion), and Ireland ($27.9 billion). America imported less than half the value of medical supplies from China in 2019 as it imported from Ireland, yet you probably didn’t hear many politicians and media personalities grandstanding about an overreliance on Irish manufacturing.

Meanwhile, an April report from the St. Louis Federal Reserve found that 70 percent of essential medical supplies consumed in the United States in 2018—including gloves, hand sanitizer, masks, and other key coronavirus-fighting stuff—were produced in the United States.

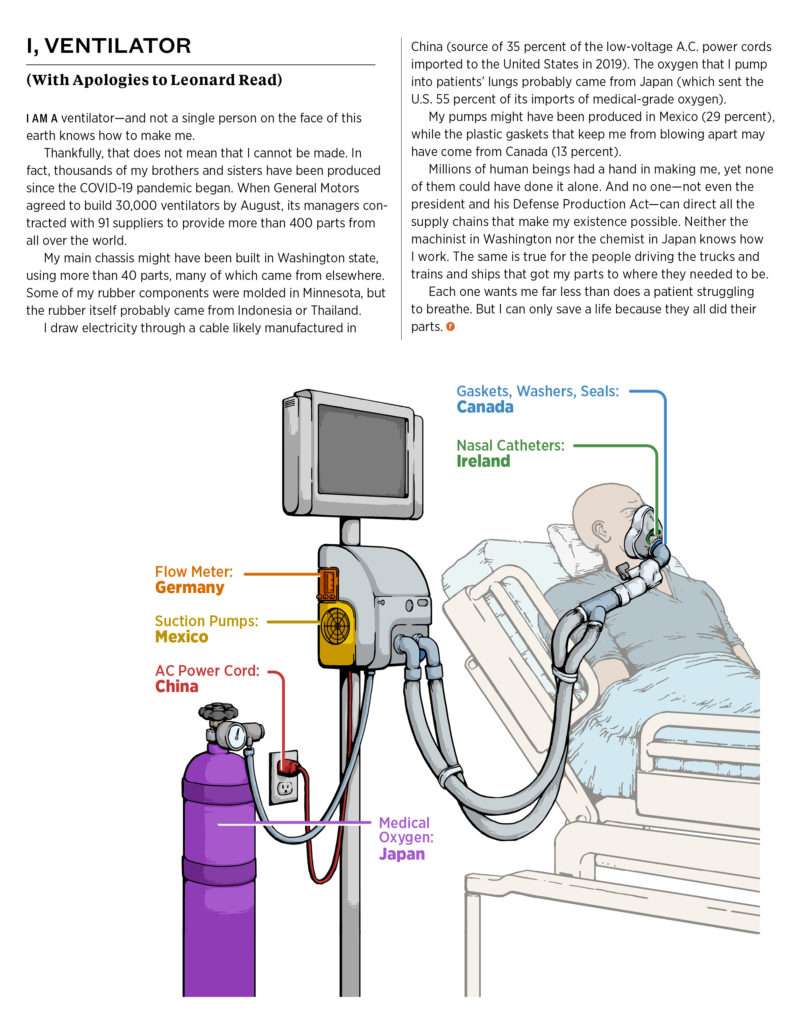

China may be more dependent on American medical exports than the other way around. That same WTO report shows that China bought more medical supplies from America than it did from any country other than Germany in each of the past three years. Is this what Navarro means when he says we are “dangerously overdependent” on global supply chains? In reality, the world’s biggest economies are deeply interdependent.

China may be more dependent on American medical exports than the other way around. That same WTO report shows that China bought more medical supplies from America than it did from any country other than Germany in each of the past three years. Is this what Navarro means when he says we are “dangerously overdependent” on global supply chains? In reality, the world’s biggest economies are deeply interdependent.

It’s true that China is the top global exporter of personal protective equipment (PPE), hand sanitizer, and some other items necessary to combat the coronavirus. But the facts are more complicated than Rubio claims.

Exports of PPE from China to Europe and the United States fell by 17 and 19 percent, respectively, during the first two months of this year—but overall exports to those same destinations fell by 20 and 28 percent, respectively, during the same period. This suggests the drop was a reflection of global economic conditions rather than a protectionist measure imposed by China on its trade partners. Exports of PPE from China to the rest of the world then increased in March, as the virus abated there and factories reopened, according to data analyzed by Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), a trade-focused think tank. Still, massive worldwide demand has continued to outstrip supply.

What about pharmaceuticals? In February, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) touched off a brief panic with a statement warning that the coronavirus outbreak in China could disrupt supply chains and lead to a shortage of drugs in America. The neo-nationalists pounced. In a February letter to the FDA, Hawley called America’s supposed dependence on Chinese-made drugs “inexcusable.” Part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the $2.3 trillion aid bill passed by Congress and signed by Trump in March, calls for the Department of Health and Human Services to develop “strategies to…encourage domestic manufacturing” of pharmaceuticals. By May, the Trump administration had approved a $350 million grant for a little-known Virginia company that promised to make drugs in the United States. “This is a great day for America,” Navarro proclaimed at a press conference.

In the rush to throw taxpayer money at the problem, the White House didn’t wait to see if a problem actually existed. On June 2, an FDA official testified that the agency had found no evidence of shortages of drugs caused by foreign governments restricting exports.

The truth is that America’s global supply lines for pharmaceutical drugs are actually quite diverse and resilient. There are roughly 2,000 manufacturing facilities around the world authorized by the FDA to produce active pharmaceutical ingredients for American consumers; only 230 of those are in China. Some 510 are in the United States, and 1,048 are in the rest of the world. The supply chains for the 370 drugs on the World Health Organization’s list of “essential medicines,” which includes “anesthetic, antibacterial, antidepressant, antiviral, cardiovascular, anti-diabetic, and gastrointestinal agents,” are similarly global: 21 percent of production facilities are in the United States, with 15 percent located in China and 64 percent located somewhere else.

Diverse supply chains have benefits. They allow drug manufacturers to operate more nimbly and efficiently, which “also offers an advantage when confronting natural disasters and other crises,” says Sally Pipes, the president and CEO of the Pacific Research Institute, a free market think tank. Pipes, who also serves as the organization’s chief fellow for health care policy, points to the example of Hurricane Maria, which devastated Puerto Rico in 2017 and disrupted operations at dozens of pharmaceutical plants on the island. Shortly after the storm hit, Scott Gottlieb, then-commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, told reporters there could be shortages of 40 different drugs.

Those shortages never materialized either, thanks to global supply chains that allowed drug manufacturers to shift production elsewhere and move supplies easily from one country to another. The same logic applies now. “The height of a deadly pandemic is the worst possible time to suddenly dismantle global drug supply chains,” Pipes says.

Casualties of a Trade War

If there is a second-worst time to start dismantling supply chains, it is immediately before a pandemic. Unfortunately, the Trump administration did that too.

As president, Trump has charted a go-it-alone strategy that emphasizes brute power over diplomatic finesse and that sees trade as a means by which other countries take advantage of the United States. Shortly after taking office in 2017, he yanked the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a 12-nation trade agreement that was widely seen as the best way to put pressure on China to change some of its unacceptable behaviors. Instead of that multilateral effort, Trump sought a one-on-one confrontation that attempted to use tariffs to bully China into changing its ways. But his trade war has so far produced only meager results.

A “phase one” agreement signed in December 2019 did nothing to offset the huge costs to both economies of the tariffs the two countries have raised against one another. And the one big “win” secured by Trump—a promise that China would buy more American agricultural goods—seems unlikely to materialize in the face of a global recession.

That lone policy victory has been offset by numerous tangible losses. Since 2018, Trump has imposed tariffs on steel, aluminum, solar panels, and washing machines. Other tariffs have been aimed at roughly $300 billion in annual imports from China—covering everything from industrial equipment to children’s toys. All together, those tariffs have sucked an estimated $80 billion out of the U.S. economy, according to an estimate from the Tax Foundation, a nonpartisan tax policy think tank.

The tariffs have also imposed a human toll, one that became more obvious during the coronavirus outbreak.

“Any disruption to this critical supply chain erodes the health care industry’s ability to deliver the quality and cost management outcomes that are key policy objectives of the country,” Matt Rowan, president of the Health Industry Distributors Association, told the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative at a hearing back in August 2018.

At the time, the administration was weighing whether to include products like hand sanitizer, thermometers, oxygen concentrators, surgical gloves, and other types of medical-grade protective gear in the list of Chinese-made items to be subjected to new tariffs. Rowan emphasized that such supplies were “essential to protecting health care providers and their patients” and would remain “a critical component of our nation’s response to public health emergencies.”

The most instantly noticeable effect of Trump’s tariffs was to increase the price of goods imported from China, including medical equipment. Importers would have no choice but to “almost immediately” pass along those price increases to “hospitals, surgery centers, long-term care facilities, individual consumers, and government programs who purchase our products,” Lara Simmons, the president of Medline Industries, one of the largest medical supply companies in the United States, said during a June 2019 hearing on the tariffs.

But the Trump administration went ahead with the tariffs anyway. Imports of medical equipment from China fell after the tariffs were imposed, and imports from other parts of the world did not increase enough to make up the difference. It’s likely that hospitals and other health care providers were drawing down on existing inventories and hoping the trade war would end before they had to restock, says PIIE’s Bown, who has analyzed changing supply chain patterns in the last few years.

Trump finally lifted tariffs on medical equipment after the pandemic struck. Unfortunately, the administration did nothing to remove tariffs on chemicals used to manufacture disinfectants and antiseptics—items that will be in even higher demand as the economy reopens.

“The tariff is making it more difficult for companies to supply our nation’s essential workers with antiseptics and sanitizing products they need to protect themselves and others from COVID-19,” says Chris Jahn, president and CEO of the American Chemistry Council.

As the COVID-19 body count rose, Trump blamed China for making things worse by lying about the seriousness of the situation in December and January. The Communist regime in Beijing does deserve scorn for misleading the world about the pandemic’s true nature during the early days of the outbreak. But Trump is far too eager to deflect blame from how his own policies weakened America’s preparedness for the disease—and from how they might have made things much worse.

Pride, Patriotism, and Profits

Having successfully implemented policies that made America less ready for the COVID-19 outbreak by reducing imports, the White House has scrambled to respond to those shortcomings…by blaming exports.

The April 2 announcement that Navarro would be in charge of the Defense Production Act’s use came after a week in which Navarro, in comments to The New York Times, had pilloried an American company for “operating like a sovereign profit-maximizing nation” and for lacking “pride and patriotism.”

That company was the Minnesota-based 3M Corp. Best known for making sticky notes and other office products, 3M also happens to be one of the world’s largest suppliers of respiratory face masks. That includes both the medical-grade N95 masks for which demand has been surging amid the COVID-19 outbreak and run-of-the-mill surgical and industrial masks.

When the coronavirus outbreak hit, 3M sprang into action: The company doubled its global production to 100 million N95 masks per month, with 35 million of those made in America. In early April, the company’s CEO, Mike Roman, announced additional investments in mask-making capacity that will allow the company to produce 50 million N95s in the U.S. by June. For that remarkable mobilization of private capital and workforce productivity in the face of a deadly pandemic, 3M earned scorn from the economic nationalists in the White House.

When Trump signed the executive order implementing the Defense Production Act on April 3, he issued a blistering statement accusing “unscrupulous brokers, distributors, and other intermediaries” of operating like “wartime profiteers” simply for selling goods to buyers in other countries. “This conduct denies our country and our people the materials they need to win the war against the virus,” Trump said. Though the formal statement did not mention 3M specifically, Trump was less diplomatic on Twitter. “We hit 3M hard today,” he wrote in a follow-up tweet, as if the company’s Minnesota headquarters were a newly discovered terrorist training ground. “[They] will have a big price to pay!”

What was 3M’s alleged crime against America? Daring to sell face masks to distributors in Canada.

Set aside the belligerence of the president’s remarks, and there is an intuitive appeal to what he’s arguing: America is facing a pandemic, the thinking goes, and we can’t afford to let go of necessary supplies—not even to a close ally like Canada. It’s every nation for itself. Shouldn’t Americans have those masks instead?

But 3M didn’t stand for the president’s shaming. In a statement, the company noted that in order to meet Americans’ needs it was importing more masks than ever from its production facilities in China. “Ceasing all export of respirators produced in the United States would likely cause other countries to retaliate and do the same, as some have already done,” 3M said. “If that were to occur, the net number of respirators being made available to the United States would actually decrease.”

The knockout blow was 3M’s revelation that its American mask production facilities rely on a special wood pulp imported from—yes—Canada. It was an incident that perfectly captured the myopia of Trump’s anti-trade agenda.

The medical supplies subject to Trump’s April 3 executive order accounted for more than $1.1 billion of U.S. exports in 2019, according to Commerce Department data analyzed by the Peterson Institute. If Trump were both constitutionally and logistically capable of stopping all exports of PPE due to the pandemic, that would mean, theoretically, that there would be $1.1 billion in additional medical gear available for American health care workers.

That’s what Trump and his allies see. What they miss is that, in 2019, the U.S. imported more than $6 billion worth of PPE from around the world. If everyone followed the logic of “every country for itself,” America would end up with a net loss of equipment totaling nearly $5 billion. This year, the gap would probably be even larger, as production everywhere has increased in response to the pandemic.

The nationalists argue that we should be willing to trade generalized economic losses for the safety and security that comes from not being dependent on other nations for critical supplies during an emergency, and that the government should enact policies to support domestic manufacturing of critical supplies.

The risks in that approach should be evident. “Suppose we made all of the medical gear in the United States that we needed, and we did this through tariffs or ‘buy local’ provisions that made it either prohibitively costly or illegal for hospitals to purchase these from anyone but ourselves,” says Bown. That’s what Trump and his allies seem to want, a reality where America is fully self-sufficient but also cut off from the rest of the world. Just look at how domestic meat supplies have been disrupted when American factories were shut down by the epidemic. What would we have done if 3M’s respirator manufacturing plants in America were our only source, but had to be closed?

As a practical matter, it is obvious that the United States would be less capable of responding to the immediate COVID-19 crisis if it stopped trading with the rest of the world. “Re-shoring to America does not imply supply chain resilience,” Bown says. “In a pandemic, excessive reliance on anyone (including yourself) is bad.”

When Trade Restrictions Spark a Backlash

Trump intuitively understands why cutting off trade in the midst of a pandemic is a mistake, even if he doesn’t fully realize it. The story of hydroxychloroquine proves as much.

In early April, the president became enamored of the anti-malarial drug, which he believed could help treat COVID-19. As a result, the White House had a brief diplomatic row with India over Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to block hydroxychloroquine exports (as part of a plan to reduce all drug exports from the country by 10 percent).

“If he doesn’t allow it to come out,” Trump told reporters on April 6, “of course there may be retaliation.”

Modi is a populist leader who has often been compared to Trump because of his nationalist rhetoric and willingness to demagogue against immigrants and minorities for political gain. He seems to view India’s domestic production of drugs such as hydroxychloroquine with the same shortsightedness that the American president applied to 3M’s mask-making operations. The dynamic was nearly identical, but the roles were flipped.

When it came to hydroxychloroquine, however, Trump was immediately able to discern why an Indian export ban was a terrible idea: It would mean American consumers might be cut off. And he was quick to threaten retaliation of the same sort the U.S. risks when denying trade to other countries.

Humanity’s fight against the coronavirus depends upon drugs made all around the world and as much PPE as can possibly be produced in short order, often by companies, such as 3M, that operate internationally. Export bans might look smart in the moment—keep those masks in America, where Americans need them—but the strategy can and will backfire. Indeed, in plenty of places, it already has.

Data collected by Simon Evenett, a professor of international trade at the University of St. Gallen and the coordinator of research for Global Trade Alert, show that 102 new limits on the export of medical gear have been imposed by 75 different governments since the beginning of the year. The results are counterproductive to fighting the coronavirus.

The Swiss medical supply outfit Hamilton Medical, for example, ramped up production by 50 percent in response to the outbreak in Europe. But then the company hit a snag. A key component of its ventilators came from Romania, a member of the European Union. Because the E.U. had imposed export restrictions on medical equipment and component parts, Hamilton Medical’s suppliers could no longer ship their wares to Switzerland, which is not an E.U. member.

“The premise of export bans—in this time of need, we need to keep our resources at home—is natural,” says Alex Tabarrok, an economist at George Mason University. “But the virus is a worldwide challenge that needs a worldwide response. We is everyone in the world.” Tabarrok says these kinds of “sicken thy neighbor” trade policies carry moral and ethical costs that go beyond the economic ones.

America’s protectionists have tried to ignore or downplay the economic harm that Trump’s go-it-alone policies have done to Americans. Those policies also mean America has less economic might with which to address a global crisis. The results could be catastrophic in humanitarian terms.

The Third World, in particular, is facing a potential perfect storm of bad trade policy. Export bans such as the ones Trump has pursued under the authority of the Defense Production Act obviously make fewer medical products available to the global market. By disrupting the flow of crucial components, trade restrictions such as the E.U.’s reduce the total amount of equipment the world can build during this time of crisis. And developing countries generally have higher tariffs to begin with—India, for example, imposes import duties on medical testing kits like the ones now being developed for detecting the coronavirus—a status quo that’s sure to hinder the flow of supplies to people who desperately need it.

“Developing countries have no production of ventilators, so they’re entirely dependent on importing the products,” says Clark Packard, trade counsel for the R Street Institute, a free market think tank. “If countries restrict exports of ventilators, it would be really gruesome.”

The Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the most populous nations in Africa, has about one such machine for every 10 million residents, according to World Health Organization data. By comparison, when the coronavirus first hit, the U.S. had about 160,000 ventilators, or roughly one for every 2,100 people. This is a problem that will not be solved with export restrictions and nationalist rhetoric in the developed world.

A Pandemic Is Not a War

Trade has been essential—and will continue to be essential—in combating the coronavirus pandemic. But tellingly, Trump views the outbreak as confirmation of his preexisting views.

“There’s nothing good about what happened with the plague,” Trump told Fox Business during a May 14 interview. “But the one thing is, it said ‘Trump was right'” about the risks of having “stupid supply chains all over the world.”

Nationalism always requires a political mobilization against some outside force. Trump has largely—though not exclusively—put China in that role. Long before he was declaring himself to be a “wartime president” in the fight against COVID-19, Trump was eager to declare what he thought would be a “good and easy to win” trade war with China as the primary opponent.

The coronavirus pandemic was not part of the plan, but it fit neatly into that narrative—and, indeed, the Chinese government’s attempt to keep the virus a secret during the early stages of the outbreak is a worse crime against the world than anything Trump has ever accused China of doing economically. It is also true, of course, that the Chinese government is a repressive dictatorship that abuses the rights of minorities and dissidents, disregards personal privacy and individual liberty, and violates international norms of commerce. And it is true, as the Trumpian nationalists like to point out, that the expansion of trade between that country and the global West has not ended these abuses.

But if you actually listen to what Trump and Navarro and the others are saying, it should become obvious that they see a confrontation with China and now the “war” against the virus as means to an end.

“We shouldn’t have supply chains. We should have them all in the United States,” Trump said in that same May 14 interview, spelling it out for all to hear. This has never been solely about strategically countering a competitor’s rise or trying to shift supply chains away from a potentially hostile communist country. It’s about autarky, or at least about detaching America from the global trading systems that have helped lift much of the world out of poverty.

That’s not a recipe for prosperity at home. It makes no more sense than suggesting that Ohio would prosper if it decided tomorrow to stop trading with the other 49 states.

Further trade restrictions will “hamstring the ability of U.S. pharmaceutical and medical equipment manufacturers to meet our future needs if firms are denied access to essential foreign supplies,” a group of more than 250 economists wrote in a May 13 letter to the White House, congressional leaders, and Trump’s top trade advisers. “Costly protectionism should not be foisted on patients at home and abroad.”

The same is true of Hawley’s latest idea: to yank the United States out of the World Trade Organization. Doing so would sever American businesses and consumers from the lower tariff rates that WTO member nations offer one another, potentially erasing $2.7 trillion in global gross domestic product, according to an analysis by two economists at the University of Indiana. Far from impoverishing Americans, as Hawley and others claim, the global trade that’s been unleashed since the WTO was founded in 1995 has contributed to a 17 percent increase in median weekly earnings for American workers. Leaving the WTO would also clear the way for China to expand its influence within that body, allowing it to dictate even more of the terms of global trade.

As the virus abates, the world will probably reconsider the approach it has taken toward China. If there are individual items for which America is heavily dependent on that country—particular medicines, perhaps—then manufacturers should look to further diversify supply chains. The federal government could encourage that behavior by lowering tariffs for imports from countries that compete with China to produce medical gear and pharmaceuticals. Pursuing nativist “buy American” policies or other forms of protectionism is neither the only solution nor the best one.

But the benefits of free trade and global economic integration created by decades of peaceful cooperation between nations should not be reconsidered. Taxing imports weakened America in advance of the pandemic. Raising barriers to trade made it more difficult to combat COVID-19 once the crisis hit. Nationalism will leave the world sicker and poorer.

Despite all that evidence to the contrary, Hawley, Trump, Navarro, and others seek to use the coronavirus as a cudgel to smash the system of global trade. They would replace it with an alternative that leaves America less free, less prosperous, and less capable of handling the next crisis.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3eem7Ni

via IFTTT