Let’s face it: There is no perfectly safe way for America to come out of its lockdown. None of the expected panaceas—a treatment or a vaccine—are in sight. America is nowhere close to having South Korea’s mass testing capacity that allowed that country to “flatten its curve.” And the longer America stays hunkered down, the more the goal of herd immunity (even if it were possible) becomes elusive, because not enough people are getting exposed and developing resistance to the virus.

Yet the economic devastation from the lockdown is becoming more intolerable, with not just livelihoods but lives on the line.

So what should America do, besides praying for a summer miracle? Start thinking of the answer not as a binary choice between “lockdown” or “liberation.” We need more targeted approaches to contain high-risk activities and protect high-risk populations while giving ordinary Americans more—not less—freedom to figure out when and how they want to return to work and some semblance of normal life.

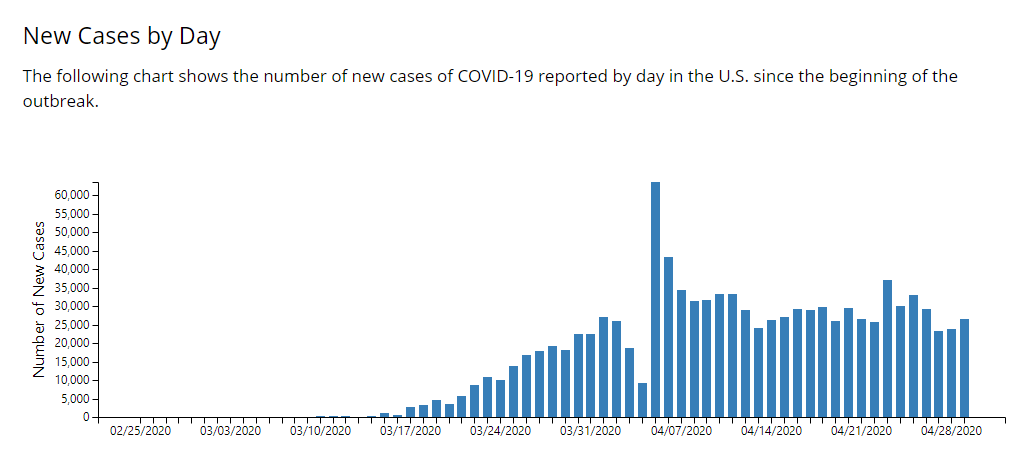

The lockdown was originally imposed because the pandemic caught America by surprise and hospitals were simply not equipped to cope with the onslaught. America already has more than 1,000,000 infected cases and over 63,000 dead.

This “achievement” has come at a hefty price. About 27 million Americans have filed for unemployment, basically wiping out all the job gains since the Great Recession. And economic output is down a stunning 30 percent. Clearly, things can’t go on this way much longer before the economic pain becomes intolerable.

Yet, notes Avik Roy, president of the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP), every major plan to phase out the lockdown relies on some combination of a vaccine, a cure, and mass testing. Given that corona is a virus, there is no guarantee that a vaccine will ever emerge—and if it does, it will probably take at least a year and a half. A treatment is more likely but is still months away. Meanwhile, America is performing fewer than 200,000 tests every day; the White House, in a much-hyped Monday announcement, promised to ramp that up to just 267,000 by the end of May. Getting to South Korea’s level will require 1,000,000 tests daily—not to mention tracing all the contacts of those who test positive and putting them in quarantine.

The Harvard Safra Center for Ethics’ bipartisan “Roadmap to Pandemic Resilience,” co-authored by Nobel laureate Paul Romer, wants five million tests per day by early June and 20 million tests per day by August, to perform repeated screening of the population to catch any secondary outbreaks. That would be terrific, but it seems like wishful thinking right now. As for herd immunity, it’s uncertain how long immunity after exposure lasts so it’s unclear whether population-wide immunity can even be achieved.

Yet Americans can’t hide forever in their homes. In fact, several more months of a blanket lockdown might mean piling an economic catastrophe on top of a health catastrophe.

So what should America do?

The first and paramount thing is to prevent health care facilities—hospitals and nursing homes—from becoming superspreaders themselves. Even in the absence of a pandemic, patients pick up 1.7 million infections in American hospitals annually and 99,000 of them die.

Jonathan Tepper, founder of Variant Perception, points out in a deeply researched article that in Wuhan, the original epicenter of the disease in China, around 41 percent of the first 138 patients diagnosed in one hospital contracted the virus in the hospital itself. Likewise, one reason why Italy’s Lombardy region might have been worse hit than neighboring Veneto is that Lombardy transported 65 percent people who tested positive into hospitals, compared to 20 percent in Veneto, exposing the virus to the entire chain of health care workers, from ambulance drivers to paramedics to doctors. A group of Lombardy doctors wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine that “hospitals might be the main COVID-19 carriers.”

It is too early to find reliable stats about coronavirus infections generated from American hospitals, but a Wall Street Journal investigation found that nursing homes in just 35 states accounted for 10,783 deaths—more than 20 percent of all U.S. fatalities. Data from five European countries shows that nursing care homes account for 42 percent to 57 percent of all coronavirus fatalities.

Meanwhile, in Canada’s largest two provinces, Ontario and Quebec, elderly patients in nursing homes make up about three quarters of all the deaths from COVID-19.

Preventing health care facilities from becoming the gasoline on the coronavirus flames has implications both for patient care and for providers. On the patients’ end, it is vital to emphasize non-hospital settings for less severe cases and to fashion coronavirus-dedicated hospitals for the more severe ones, as South Korea did nationwide and as some hospitals have come around to doing in America.

On the provider end, America must race to procure protective gear—masks, gowns, glasses—for frontline staff. Shortages compromise not only their safety but their patients’ too. Similarly, until America can build ubiquitous testing capacity, it will have to prioritize testing medical staff. It is less important to chase down asymptomatic carriers, the celebrated writer-cum-surgeon Atul Gawande points out. South Korea didn’t.

Meanwhile, hospitals also need to beef up their hygienic practices and embrace a “checklist” that Gawande has long been crusading for. This simple and powerful idea, which has resulted in a stunning drop of hospital infections when tried, would involve creating a coronavirus-appropriate protocol of hygiene—washing hands, disinfecting the patient before touching, wearing masks and gowns—and then having physicians attest that they have adhered to every item on it by check-marking each one before interacting with patients.

In addition to this focus on hospitals, any reopening plan has to beware of other superspreading venues, such as mass transit, and superspreading events, such as games, concerts, and campaigns.

Furthermore, around 78 percent of the coronavirus deaths are concentrated in those over 65. Indeed, there is a 22-fold difference in the death rate between 25-to-54-year-olds and the over-65 cohort, with children facing very few deaths. Yet blanket lockdowns treat everyone as if they are equally affected.

Given the differential impact, Roy recommends a strategy that allows young people to get back to normal life as much as is safely possible. This means reopening schools and lifting stay-at-home orders for all but the elderly or those with underlying conditions that make them more susceptible.

Of course, the young and the old are not sealed off populations. Indeed, most young people have high-risk individuals such as elderly relatives among their close circle of loved ones. So there is no denying there will be an all-around increase in risk for everyone after reopening. Yet some increase in risk might be worth taking: If the economy decays beyond a point, it’ll eat into the country’s medical capacity to fight the disease—not to mention its capacity to hand costly rescue packages to affected workers.

Whatever the downside of the lockdown, its one very great advantage is that it vastly accelerated the national learning curve on radical social distancing and other precautions. Preventative practices have become part of the national fabric; even if the lockdown is relaxed, few people will go back to their pre-coronavirus lifestyle. So it is not pollyannish to believe that this, combined with greater precautions against superspreaders, will diminish the toll from any follow-up outbreaks.

Rolling back the lockdown will also give businesses the freedom to come up with innovative adaptive strategies. Essential businesses that were allowed to remain open have found all kinds of ways to enhance consumer safety—plexiglass spit barriers at grocery store check out counters, disinfecting every cart. There is every reason to believe that “inessential” businesses will do the same when given the chance.

Coronavirus is a cruel microbe. But we will have to find more clever ways of fighting it than mass captivity.

A version of this column originally appeared in The Week.

Bonus reading: Reason Foundation just released its working paper for an evidence-based approach for easing lockdowns. It takes a comprehensive look at which approaches have worked and which haven’t.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2Sq5mGS

via IFTTT