What does it mean (as a legal term, not a medical one)? And where?

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3vqWdPd

via IFTTT

another site

What does it mean (as a legal term, not a medical one)? And where?

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3vqWdPd

via IFTTT

What does it mean (as a legal term, not a medical one)? And where?

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3vqWdPd

via IFTTT

Did you know that the international community coordinates on their financial surveillance systems? Many Americans don’t even know that our own Treasury Department and banking system keeps tabs on our financial activities every day. This quiet financial surveillance, overseen mostly by an organization called the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), is expansive enough. Unfortunately, a new proposal on cryptocurrency transactions from the international equivalent of FinCEN, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), threatens to be even more aggressive in spying on financial activities.

The FATF describes itself as a “global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.” It is an inter-governmental body that sets regulatory standards for the more than 200 countries and jurisdictions that heed its advice. The FATF issues periodic recommendations for how these institutions should set up what’s called anti-money laundering/know your customer (AML/KYC) rules, which mostly require that financial systems collect and maintain private records on billions of people across the world. Their recommendations don’t have the immediate force of law, but member states and allies take their rubrics very seriously as they craft their own rules.

The gang has been around since 1989, and FATF has expanded its recommendations and scope along with the trials of the times. September 11 was a biggie for the FATF, as the organization pivoted to focus on terrorist financing. The new millennium also saw the addition of a jurisdictional blacklist, which is a who’s who of those currently on the outs with the international order. Today, it includes Iran and North Korea.

As you might imagine, the rise of cryptocurrencies has been of great interest to the FATF. These technologies allow for direct value transfer online. As such, they fit awkwardly upon an international surveillance network premised upon collections obligations by third-party financial facilitators.

It’s useful to start with how financial reporting requirements have traditionally applied. Monetary surveillance operates through service providers in our financial system. They are supposed to review transactions for anything that looks suspicious or indicative of things like money laundering or tax evasion. Sometimes that means keeping records on large or international transfers. Sometimes that means notifying the feds if something looks particularly dodgy in the eyes of the government. It often means that third-party financial institutions keep detailed personal information on all customers, even to just open an account.

But notice what is not included: many kinds of cash transactions among individuals or most businesses. You don’t need to collect someone’s ID before accepting cash for a run-of-the-mill transaction. This doesn’t mean that crimes can’t be committed with such transactions. It’s logistically unworkable and would be an even more extreme burden on privacy than the third-party-operated financial surveillance we have in place. So such private transfers are thankfully exempt from financial reporting requirements.

With a direct cryptocurrency transaction, where there is no bank, there is no potential for a bank to collect data on transactions. It’s like a cash transaction. For these reasons, FinCEN has generally updated its financial reporting obligations to clarify that AML/KYC rules do not apply to fully decentralized transactions or applications, as they are similarly logistically unworkable. America’s top AML/KYC cop hasn’t gotten everything with cryptocurrency right, and it is currently proposing rules that would expand financial surveillance for direct virtual currency transactions, but its rules have at least been mostly consistent with how we treat cash transactions in the past.

Not so with the FATF. Its most recent draft guidance proposes a self-described “expansive” standard for cryptocurrency (what they call virtual asset service providers or VASPs) surveillance that could threaten the privacy and safety of innocent users across the world. Peter Van Valkenburgh of Coin Center, a cryptocurrency advocacy group, has the rundown on the biggest problems with the FATF proposal.

Two major errors permeate the document. First, it’s just internally inconsistent. A cryptocurrency user or business or developer that earnestly wants to comply with the FATF standards as written would have a hard time knowing whether or not they would be legally considered a VASP.

For instance, at one point, the FATF says that “one may develop and sell virtual asset platform software without being a VASP.” That’s great to hear! Software developers almost never act as cryptocurrency custodians, so they should be exempt from financial reporting requirements as they wouldn’t have access to this data anyway.

But wait a second. Elsewhere in the document, the FATF says “one may not deploy programs whose functions fall under the definition of VASP.” Huh? So if a software developer pushes a live version of software that a custodian uses, they’re in trouble? Which one is it?

There are similar contradictions throughout: “one may develop and sell virtual asset platform software without being a VASP” but “one may not automate a process that provides covered services without being a VASP”; then “one will be a VASP if they can conduct a transaction on behalf of another person” but “being unable to complete a transaction does not disqualify you from being a VASP.” How is the cryptocurrency community supposed to comply with rules that are so paradoxical?

This brings us to the second major problem. As currently written, if these inconsistencies are resolved, they may likely be in the direction of more surveillance. The FATF says that it developed these new rules to purposefully be “expansive.” No longer will the international standard for financial reporting requirements be mostly limited to third-party custodians with control of customer funds. Rather, when it comes to cryptocurrency, now all sorts of non-custodians may be unceremoniously deputized as financial snoops, including those merely “conducting business development,” “facilitating transactions” (a.k.a. mining), “integrating software into telecommunications platforms,” “deploying programs,” and “changing rules within software protocols.”

This is not only a huge logistical headache for the hundreds of thousands of people around the world who engage in these activities every day and yet have no access to the kind of data that might be required of them. It’s a major threat to the privacy of billions of innocents around the globe.

Van Valkenburgh points out that many FATF members are also signatories or at least aligned with the values of documents such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and the U.S. Constitution. These agreements outline and protect human rights to privacy and expression that are threatened by the kind of expansive surveillance proposed by the new rules.

This is before getting into the counterproductive tactic of making it harder for honest cryptocurrency users to comply with non-workable financial reporting requirements. Bad actors will find ways to send money using cash, virtual cash, or maybe World of Warcraft gold. They weren’t too keen on using regulated third parties, anyway. These proposed financial reporting requirements will only make it harder for non-criminals to access the financial channels they need while pushing the criminals further underground.

The good news about the proposed rules is that they are still merely a draft. There is time to work with the FATF to improve the language so that it is clearer and more appropriate and respectful of our human rights to privacy. Still, it is concerning that these errors regarding cryptocurrency operations and our rights to privacy are still common in the highest levels of policymaking. It’s a reminder that although established institutions do have self-interested incentives to crack down on cryptocurrency, a lot of times, they just don’t know what it is they are looking at.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/32QbZqC

via IFTTT

Did you know that the international community coordinates on their financial surveillance systems? Many Americans don’t even know that our own Treasury Department and banking system keeps tabs on our financial activities every day. This quiet financial surveillance, overseen mostly by an organization called the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), is expansive enough. Unfortunately, a new proposal on cryptocurrency transactions from the international equivalent of FinCEN, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), threatens to be even more aggressive in spying on financial activities.

The FATF describes itself as a “global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.” It is an inter-governmental body that sets regulatory standards for the more than 200 countries and jurisdictions that heed its advice. The FATF issues periodic recommendations for how these institutions should set up what’s called anti-money laundering/know your customer (AML/KYC) rules, which mostly require that financial systems collect and maintain private records on billions of people across the world. Their recommendations don’t have the immediate force of law, but member states and allies take their rubrics very seriously as they craft their own rules.

The gang has been around since 1989, and FATF has expanded its recommendations and scope along with the trials of the times. September 11 was a biggie for the FATF, as the organization pivoted to focus on terrorist financing. The new millennium also saw the addition of a jurisdictional blacklist, which is a who’s who of those currently on the outs with the international order. Today, it includes Iran and North Korea.

As you might imagine, the rise of cryptocurrencies has been of great interest to the FATF. These technologies allow for direct value transfer online. As such, they fit awkwardly upon an international surveillance network premised upon collections obligations by third-party financial facilitators.

It’s useful to start with how financial reporting requirements have traditionally applied. Monetary surveillance operates through service providers in our financial system. They are supposed to review transactions for anything that looks suspicious or indicative of things like money laundering or tax evasion. Sometimes that means keeping records on large or international transfers. Sometimes that means notifying the feds if something looks particularly dodgy in the eyes of the government. It often means that third-party financial institutions keep detailed personal information on all customers, even to just open an account.

But notice what is not included: many kinds of cash transactions among individuals or most businesses. You don’t need to collect someone’s ID before accepting cash for a run-of-the-mill transaction. This doesn’t mean that crimes can’t be committed with such transactions. It’s logistically unworkable and would be an even more extreme burden on privacy than the third-party-operated financial surveillance we have in place. So such private transfers are thankfully exempt from financial reporting requirements.

With a direct cryptocurrency transaction, where there is no bank, there is no potential for a bank to collect data on transactions. It’s like a cash transaction. For these reasons, FinCEN has generally updated its financial reporting obligations to clarify that AML/KYC rules do not apply to fully decentralized transactions or applications, as they are similarly logistically unworkable. America’s top AML/KYC cop hasn’t gotten everything with cryptocurrency right, and it is currently proposing rules that would expand financial surveillance for direct virtual currency transactions, but its rules have at least been mostly consistent with how we treat cash transactions in the past.

Not so with the FATF. Its most recent draft guidance proposes a self-described “expansive” standard for cryptocurrency (what they call virtual asset service providers or VASPs) surveillance that could threaten the privacy and safety of innocent users across the world. Peter Van Valkenburgh of Coin Center, a cryptocurrency advocacy group, has the rundown on the biggest problems with the FATF proposal.

Two major errors permeate the document. First, it’s just internally inconsistent. A cryptocurrency user or business or developer that earnestly wants to comply with the FATF standards as written would have a hard time knowing whether or not they would be legally considered a VASP.

For instance, at one point, the FATF says that “one may develop and sell virtual asset platform software without being a VASP.” That’s great to hear! Software developers almost never act as cryptocurrency custodians, so they should be exempt from financial reporting requirements as they wouldn’t have access to this data anyway.

But wait a second. Elsewhere in the document, the FATF says “one may not deploy programs whose functions fall under the definition of VASP.” Huh? So if a software developer pushes a live version of software that a custodian uses, they’re in trouble? Which one is it?

There are similar contradictions throughout: “one may develop and sell virtual asset platform software without being a VASP” but “one may not automate a process that provides covered services without being a VASP”; then “one will be a VASP if they can conduct a transaction on behalf of another person” but “being unable to complete a transaction does not disqualify you from being a VASP.” How is the cryptocurrency community supposed to comply with rules that are so paradoxical?

This brings us to the second major problem. As currently written, if these inconsistencies are resolved, they may likely be in the direction of more surveillance. The FATF says that it developed these new rules to purposefully be “expansive.” No longer will the international standard for financial reporting requirements be mostly limited to third-party custodians with control of customer funds. Rather, when it comes to cryptocurrency, now all sorts of non-custodians may be unceremoniously deputized as financial snoops, including those merely “conducting business development,” “facilitating transactions” (a.k.a. mining), “integrating software into telecommunications platforms,” “deploying programs,” and “changing rules within software protocols.”

This is not only a huge logistical headache for the hundreds of thousands of people around the world who engage in these activities every day and yet have no access to the kind of data that might be required of them. It’s a major threat to the privacy of billions of innocents around the globe.

Van Valkenburgh points out that many FATF members are also signatories or at least aligned with the values of documents such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and the U.S. Constitution. These agreements outline and protect human rights to privacy and expression that are threatened by the kind of expansive surveillance proposed by the new rules.

This is before getting into the counterproductive tactic of making it harder for honest cryptocurrency users to comply with non-workable financial reporting requirements. Bad actors will find ways to send money using cash, virtual cash, or maybe World of Warcraft gold. They weren’t too keen on using regulated third parties, anyway. These proposed financial reporting requirements will only make it harder for non-criminals to access the financial channels they need while pushing the criminals further underground.

The good news about the proposed rules is that they are still merely a draft. There is time to work with the FATF to improve the language so that it is clearer and more appropriate and respectful of our human rights to privacy. Still, it is concerning that these errors regarding cryptocurrency operations and our rights to privacy are still common in the highest levels of policymaking. It’s a reminder that although established institutions do have self-interested incentives to crack down on cryptocurrency, a lot of times, they just don’t know what it is they are looking at.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/32QbZqC

via IFTTT

From Sitelock LLC v. GoDaddy.com LLC, released Thursday by Judge Dominic W. Lanza:

In an order issued earlier this year, the Court observed that “[t]his case has been marred by a seemingly endless series of discovery disputes” and then proceeded to resolve the parties’ latest batch of squabbles. Here we go again. Pending before the Court are two more discovery-related motions: (1) GoDaddy’s motion for a protective order and (2) SiteLock’s motion to compel. Also pending are GoDaddy’s five motions to seal….

As to the discovery-related disputes, I’ll just quote the introductory line:

What a mess. Each side’s affirmative requests for relief are denied.

As to sealing, the court writes (among other things):

The Court is once again bogged down by the “tedious, time-consuming” task of reviewing motions to seal huge quantities of material due to GoDaddy’s “failure to carefully consider whether each proposed redaction”—or request to seal a document in full—”was, in fact, necessary.” The parties have repeatedly been admonished that any sealing request must explain “with specificity” why the material in question meets the standard for sealing.

Furthermore, the Court has repeatedly ordered that any sealing request seeking redactions be accompanied by a version, lodged under seal, in which each proposed redaction is highlighted to facilitate the Court’s review and to obviate the need for side-by-side comparison of drafts to determine what material has been redacted….

The public has a general right to inspect judicial records and documents, such that a party seeking to seal a judicial record must overcome “a strong presumption in favor of access.” To do so, the party must “articulate compelling reasons supported by specific factual findings that outweigh the general history of access and the public policies favoring disclosure….” The Court must then “conscientiously balance the competing interests of the public and the party who seeks to keep certain judicial records secret.” “After considering these interests, if the court decides to seal certain judicial records, it must base its decision on a compelling reason and articulate the factual basis for its ruling, without relying on hypothesis or conjecture.”

The “stringent” compelling reasons standard applies to all filed motions and their attachments where the motion is “more than tangentially related to the merits of a case.” However, a lower standard applies to “sealed materials attached to a discovery motion unrelated to the merits of a case,” which requires only that a party establish “good cause” for sealing.

GoDaddy’s motion for a protective order and SiteLock’s motion to compel are more than tangentially related to the merits of this case—they involve matters that go to the heart of this litigation. Indeed, one of the sentences that GoDaddy seeks to redact from SiteLock’s motion to compel—a sentence that clearly doesn’t meet the sealing standard and will not be redacted—states that “GoDaddy’s unproduced records of its sales of product bundles that included SiteLock,” which is the topic of most of the material sought to be sealed, “are central to SiteLock’s claims.” For these reasons, the Court concludes that the stringent “compelling reasons” standard likely applies here. With that said, the determination of the applicable standard is ultimately irrelevant because GoDaddy’s sealing requests would fail even if evaluated under the lesser “good cause” standard….

GoDaddy’s motions fail to follow the Court’s repeated instructions and fail to establish that the standard for sealing is satisfied….

GoDaddy’s motion to seal portions of Exhibits E, F, and H to its reply in support of its motion for protective order is accompanied by unredacted versions of these documents, lodged under seal, without the required, court-ordered highlighting. The motion identifies sixteen large blocks of proposed redactions ….

GoDaddy devotes one paragraph (17 lines of text) of its memorandum to making sweeping generalizations about 28 pages of proposed redactions to Liang’s deposition testimony. GoDaddy broadly asserts that the proposed redactions cover “sensitive business matters, including GoDaddy’s internal proprietary technology and processes and the internal terminology used to describe same” as well as “commercially sensitive information regarding GoDaddy’s strategic approach to marketing and advertising certain products, including both SiteLock and other (non-party) products, and the related product costs.” GoDaddy further asserts that, buried somewhere within the 28 pages of proposed redactions, there are “references to (a) a “CONFIDENTIAL” email chain regarding SiteLock sales revenue; and (b) a document this Court previously approved as being filed under seal. This is a far cry from the Court’s repeated direction that redaction requests should, “with specificity,” identify what is sensitive about each “particular sentence or phrase” to be redacted. Instead, GoDaddy places the onus on the Court to review large sections of a deposition transcript to determine whether they are subject to sealing in full. [Further details omitted. -EV] …

The parties’ excessive sealing requests have placed an undue burden on the Court’s time and resources. The Court has been asked repeatedly “to decide a sometimes complex issue of sealing or redaction with no adversarial briefing and often, as in this case, with only a perfunctory submission from the party seeking relief.” Additionally, court orders designed to streamline the sealing process have been inexplicably ignored.

The unacceptably vague sealing requests, along with the parties’ seemingly endless discovery requests, have bogged down this case. The Court is mindful of the public’s interest in the expeditious resolution of lawsuits and of its inherent power and duty to control its own docket. The Court is authorized to “manage cases so that disposition is expedited, wasteful pretrial activities are discouraged, the quality of the trial is improved, and settlement is facilitated” and to adopt “special procedures for managing potentially difficult or protracted actions.”

Generally, when a motion to seal is denied, “the lodged document will not be filed” and the submitting party “may” resubmit the document for filing in the public record. Where the proponent of the motion to seal is also the party that wished to file the document, the Court has often given that party the option to (1) file the document in the public record, (2) make another attempt at an adequate motion to seal, or (3) withdraw the document and revise whatever brief had relied upon that document to omit the relevant citations.

But here, the substandard motions to seal and the extensive amount of proposed redactions, many of which common sense indicates are not subject to sealing, threaten to create untenable further delay in this action. The Court will not permit a new round of motions to seal, which would postpone resolution of the discovery disputes. Instead, all of the materials submitted by both parties will be filed in the public record, with the exception of Exhibit H to GoDaddy’s reply in support of its motion for protective order and Exhibits 7 and 13 of SiteLock’s motion to compel, which may be filed under seal. See, e.g., GoDaddy.com LLC v. RPost Comms. Ltd., 2016 WL 1158851, *4, (D. Ariz. 2016) (denying certain sealing requests by GoDaddy, noting that “GoDaddy’s explanations for sealing [were] generalized in nature … and lack[ed] substantiation,” and ordering the clerk of court to “unseal and file” the lodged documents in lieu of allowing another round of sealing requests)….

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3dWccze

via IFTTT

From Sitelock LLC v. GoDaddy.com LLC, released Thursday by Judge Dominic W. Lanza:

In an order issued earlier this year, the Court observed that “[t]his case has been marred by a seemingly endless series of discovery disputes” and then proceeded to resolve the parties’ latest batch of squabbles. Here we go again. Pending before the Court are two more discovery-related motions: (1) GoDaddy’s motion for a protective order and (2) SiteLock’s motion to compel. Also pending are GoDaddy’s five motions to seal….

As to the discovery-related disputes, I’ll just quote the introductory line:

What a mess. Each side’s affirmative requests for relief are denied.

As to sealing, the court writes (among other things):

The Court is once again bogged down by the “tedious, time-consuming” task of reviewing motions to seal huge quantities of material due to GoDaddy’s “failure to carefully consider whether each proposed redaction”—or request to seal a document in full—”was, in fact, necessary.” The parties have repeatedly been admonished that any sealing request must explain “with specificity” why the material in question meets the standard for sealing.

Furthermore, the Court has repeatedly ordered that any sealing request seeking redactions be accompanied by a version, lodged under seal, in which each proposed redaction is highlighted to facilitate the Court’s review and to obviate the need for side-by-side comparison of drafts to determine what material has been redacted….

The public has a general right to inspect judicial records and documents, such that a party seeking to seal a judicial record must overcome “a strong presumption in favor of access.” To do so, the party must “articulate compelling reasons supported by specific factual findings that outweigh the general history of access and the public policies favoring disclosure….” The Court must then “conscientiously balance the competing interests of the public and the party who seeks to keep certain judicial records secret.” “After considering these interests, if the court decides to seal certain judicial records, it must base its decision on a compelling reason and articulate the factual basis for its ruling, without relying on hypothesis or conjecture.”

The “stringent” compelling reasons standard applies to all filed motions and their attachments where the motion is “more than tangentially related to the merits of a case.” However, a lower standard applies to “sealed materials attached to a discovery motion unrelated to the merits of a case,” which requires only that a party establish “good cause” for sealing.

GoDaddy’s motion for a protective order and SiteLock’s motion to compel are more than tangentially related to the merits of this case—they involve matters that go to the heart of this litigation. Indeed, one of the sentences that GoDaddy seeks to redact from SiteLock’s motion to compel—a sentence that clearly doesn’t meet the sealing standard and will not be redacted—states that “GoDaddy’s unproduced records of its sales of product bundles that included SiteLock,” which is the topic of most of the material sought to be sealed, “are central to SiteLock’s claims.” For these reasons, the Court concludes that the stringent “compelling reasons” standard likely applies here. With that said, the determination of the applicable standard is ultimately irrelevant because GoDaddy’s sealing requests would fail even if evaluated under the lesser “good cause” standard….

GoDaddy’s motions fail to follow the Court’s repeated instructions and fail to establish that the standard for sealing is satisfied….

GoDaddy’s motion to seal portions of Exhibits E, F, and H to its reply in support of its motion for protective order is accompanied by unredacted versions of these documents, lodged under seal, without the required, court-ordered highlighting. The motion identifies sixteen large blocks of proposed redactions ….

GoDaddy devotes one paragraph (17 lines of text) of its memorandum to making sweeping generalizations about 28 pages of proposed redactions to Liang’s deposition testimony. GoDaddy broadly asserts that the proposed redactions cover “sensitive business matters, including GoDaddy’s internal proprietary technology and processes and the internal terminology used to describe same” as well as “commercially sensitive information regarding GoDaddy’s strategic approach to marketing and advertising certain products, including both SiteLock and other (non-party) products, and the related product costs.” GoDaddy further asserts that, buried somewhere within the 28 pages of proposed redactions, there are “references to (a) a “CONFIDENTIAL” email chain regarding SiteLock sales revenue; and (b) a document this Court previously approved as being filed under seal. This is a far cry from the Court’s repeated direction that redaction requests should, “with specificity,” identify what is sensitive about each “particular sentence or phrase” to be redacted. Instead, GoDaddy places the onus on the Court to review large sections of a deposition transcript to determine whether they are subject to sealing in full. [Further details omitted. -EV] …

The parties’ excessive sealing requests have placed an undue burden on the Court’s time and resources. The Court has been asked repeatedly “to decide a sometimes complex issue of sealing or redaction with no adversarial briefing and often, as in this case, with only a perfunctory submission from the party seeking relief.” Additionally, court orders designed to streamline the sealing process have been inexplicably ignored.

The unacceptably vague sealing requests, along with the parties’ seemingly endless discovery requests, have bogged down this case. The Court is mindful of the public’s interest in the expeditious resolution of lawsuits and of its inherent power and duty to control its own docket. The Court is authorized to “manage cases so that disposition is expedited, wasteful pretrial activities are discouraged, the quality of the trial is improved, and settlement is facilitated” and to adopt “special procedures for managing potentially difficult or protracted actions.”

Generally, when a motion to seal is denied, “the lodged document will not be filed” and the submitting party “may” resubmit the document for filing in the public record. Where the proponent of the motion to seal is also the party that wished to file the document, the Court has often given that party the option to (1) file the document in the public record, (2) make another attempt at an adequate motion to seal, or (3) withdraw the document and revise whatever brief had relied upon that document to omit the relevant citations.

But here, the substandard motions to seal and the extensive amount of proposed redactions, many of which common sense indicates are not subject to sealing, threaten to create untenable further delay in this action. The Court will not permit a new round of motions to seal, which would postpone resolution of the discovery disputes. Instead, all of the materials submitted by both parties will be filed in the public record, with the exception of Exhibit H to GoDaddy’s reply in support of its motion for protective order and Exhibits 7 and 13 of SiteLock’s motion to compel, which may be filed under seal. See, e.g., GoDaddy.com LLC v. RPost Comms. Ltd., 2016 WL 1158851, *4, (D. Ariz. 2016) (denying certain sealing requests by GoDaddy, noting that “GoDaddy’s explanations for sealing [were] generalized in nature … and lack[ed] substantiation,” and ordering the clerk of court to “unseal and file” the lodged documents in lieu of allowing another round of sealing requests)….

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3dWccze

via IFTTT

Limited access to justice is a reality for most people. It is estimated that the legal profession fails to serve 80 percent of the public and continues to build access barriers for people seeking legal services. The Legal Services Corporation indicates that the problem is particularly acute for low-income Americans because 86 percent of their civil legal problems have not been addressed with adequate or professional legal help.

People representing themselves are at a disadvantage. The National Center for State Courts found, for example, that 75 percent of civil matters in major urban areas had at least one self-represented party; those parties are less likely to prevail in court. Others who cannot afford legal assistance end up stuck in horrific circumstances, such as domestic violence, that should be criminal matters.

A few states have taken preliminary steps to improve access to legal services and some legal scholars and practitioners are clearly concerned about the problem. For example, Judge Richard Posner abruptly retired from the bench in 2017 to assist less-affluent people with valid legal claims because he believed that the courts were not fairly treating litigants who could not afford a lawyer. However, the profession overall is doing little to significantly increase access to justice. The 1 to 2 percent of all legal effort that consists of pro bono service to the poor is not a solution to excessive prices for basic services that most people cannot afford, such as $1500 for a simple contract.

Generally, high prices that persist in an industry can be reduced by additional competition that causes incumbent suppliers to reduce their costs and prices and includes new industry entrants that might become low-cost producers that cause prices to fall even further. Accordingly, Trouble at the Bar calls for deregulating the legal profession to eliminate entry barriers, increase competition, reduce prices, and increase access to justice.

Deregulation encompasses eliminating the American Bar Association’s control over legal education and eliminating mandatory state licensing requirements. The ABA accredits law schools that offer an acceptable three-year course of study, which students generally complete—and are often required to complete—before taking a state bar examination to obtain a license to practice law. However, many people who are interested in providing legal services cannot afford the out-of-pocket costs and opportunity cost of not working for three years to obtain a law degree. Those who can often take a high-paying job instead of a lower-paying, public-interest job to pay off their accumulated law school debt.

Eliminating requirements to attend an ABA-accredited law school would allow legal education to evolve and respond to the diverse interests of potential new legal service providers who could help the public without graduating from a costly ABA-accredited law school. Alternative educational institutions would offer new programs, including but not limited to specialized vocational and online courses of study that could be completed in less than a year. Those could greatly expand the provision of effective, low-cost civil legal services.

In addition, new programs would enable college undergraduates to major in and receive a bachelor’s degree in law. Some graduates could immediately provide valuable legal services that did not require advanced coursework or considerable experience. Other graduates could complete an accelerated law school program in much less than three years, as occurs in Europe.

Deregulation seeks to increase competition for and alternatives to incumbent suppliers, not to prohibit their existence. So, traditional three-year law schools would continue to exist, and the ABA could continue to accredit law schools, as could any other accrediting institution that develops. The competition from alternative legal education programs would force traditional law schools to reduce their tuition. As a result, more graduates would be less encumbered by debt and more likely to pursue a career in public-interest law.

Entry deregulation would allow any individual to offer legal services without requiring them to obtain a specific legal education and to pass a state bar examination. Again, individuals would be free to attend traditional ABA-accredited law schools, take bar examinations, and acquire any other form of certification. Deregulation would also allow any firm or corporation, including foreign entities, to provide legal services without being owned by lawyers.

Firms in other industries operate ethically as public corporations; the exclusion of corporations providing legal services has been justified on the unsubstantiated grounds that corporations would be conflicted between representing their shareholders and their clients. The evidence from Washington, DC, which permits an Alternative Business Structure with nonlawyer ownership of a law firm, does not indicate that nonlawyer owners have pressured lawyers into ethics violations.

In sum, deregulation would lead to a more heterogeneous supply of lawyers and more intense competition among incumbent law firms and new legal service entrants. New low-cost legal services would be offered, current legal services would be offered at lower prices, and leaders of the global legal service industry would pioneer adoption of technological innovations that further reduce costs and prices for many services.

Some object that deregulation is likely to increase the number of lawyers, which includes legal service providers without a JD from an ABA-accredited law school, when the United States already has too many lawyers. However, this objection fails to consider that the equilibrium of supply and demand determines the number of lawyers.

The current high prices for legal services that reduce demand and the barriers to legal practice that reduce supply suggest that 1.3 million US lawyers are too few, not too many, and help explain why the United States ranks below other countries in terms of the accessibility and affordability of civil legal services. By decreasing the price of legal services and increasing the supply of lawyers, albeit increasing the share of low-cost legal service providers, which, as noted, will be part of the legal profession, and those wishing to practice public-interest law, deregulation would benefit the public by increasing the equilibrium number of lawyers.

Other objections to deregulating the legal profession are based on either a lack of appreciation of deregulation’s likely effects or a misunderstanding of what deregulation means. Trouble at the Bar argues that in practice, ABA regulations and education requirements do little to improve the quality of legal services. Scholars continue to debate why ABA regulations and education requirements were even adopted. In any case, states did not quickly adopt them to improve the quality of legal services for an allegedly uninformed public. Indeed, state legislatures took decades to adopt ABA education requirements because many state legislators themselves were graduates of unaccredited law schools and they would have to admit that they were not qualified to practice law!

Market forces have created websites, such as Angie’s List and Yelp, as well as social media platforms, which can accurately inform consumers about the quality, reputation, and performance of a broad range of service providers. Similar websites, such as AVVO and Martindale-Hubble, currently exist for lawyers. Others would proliferate, offering even more detailed information about legal service providers for a larger, more discerning, and more heterogenous volume of consumers.

Critics also assert that deregulation of lawyers is tantamount to advocating that doctors should not have to go to medical school, complete residency training, and obtain a license to practice medicine. As noted, no one would have to hire a lawyer who did not go to law school or pass a bar examination. Those who did would undoubtedly require credible evidence that the legal service provider was competent to perform the desired legal service.

Deregulation simply allows the market, not self-interested institutions, to determine the extent and type of legal education and credentials that are appropriate for a lawyer to perform specific services demanded by clients. Clearly, legal service providers who are assisting someone with a basic contract do not need to demonstrate the same level of competence, as indicated by educational degrees and professional accomplishments, as a lawyer representing a client before the Supreme Court or defending a homicide charge.

Finally, critics assert that many jobs, such as social workers, advocates, and paralegals, already exist to help alleviate legal problems, yet they ignore that most of the public is still not served by the legal profession. Deregulation would enable considerably more of the public to afford legal services at prices that, in general, would be markedly below current prices. Thus, the “law of demand” and new sources of supply would greatly expand access to justice.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3tYKnM1

via IFTTT

Limited access to justice is a reality for most people. It is estimated that the legal profession fails to serve 80 percent of the public and continues to build access barriers for people seeking legal services. The Legal Services Corporation indicates that the problem is particularly acute for low-income Americans because 86 percent of their civil legal problems have not been addressed with adequate or professional legal help.

People representing themselves are at a disadvantage. The National Center for State Courts found, for example, that 75 percent of civil matters in major urban areas had at least one self-represented party; those parties are less likely to prevail in court. Others who cannot afford legal assistance end up stuck in horrific circumstances, such as domestic violence, that should be criminal matters.

A few states have taken preliminary steps to improve access to legal services and some legal scholars and practitioners are clearly concerned about the problem. For example, Judge Richard Posner abruptly retired from the bench in 2017 to assist less-affluent people with valid legal claims because he believed that the courts were not fairly treating litigants who could not afford a lawyer. However, the profession overall is doing little to significantly increase access to justice. The 1 to 2 percent of all legal effort that consists of pro bono service to the poor is not a solution to excessive prices for basic services that most people cannot afford, such as $1500 for a simple contract.

Generally, high prices that persist in an industry can be reduced by additional competition that causes incumbent suppliers to reduce their costs and prices and includes new industry entrants that might become low-cost producers that cause prices to fall even further. Accordingly, Trouble at the Bar calls for deregulating the legal profession to eliminate entry barriers, increase competition, reduce prices, and increase access to justice.

Deregulation encompasses eliminating the American Bar Association’s control over legal education and eliminating mandatory state licensing requirements. The ABA accredits law schools that offer an acceptable three-year course of study, which students generally complete—and are often required to complete—before taking a state bar examination to obtain a license to practice law. However, many people who are interested in providing legal services cannot afford the out-of-pocket costs and opportunity cost of not working for three years to obtain a law degree. Those who can often take a high-paying job instead of a lower-paying, public-interest job to pay off their accumulated law school debt.

Eliminating requirements to attend an ABA-accredited law school would allow legal education to evolve and respond to the diverse interests of potential new legal service providers who could help the public without graduating from a costly ABA-accredited law school. Alternative educational institutions would offer new programs, including but not limited to specialized vocational and online courses of study that could be completed in less than a year. Those could greatly expand the provision of effective, low-cost civil legal services.

In addition, new programs would enable college undergraduates to major in and receive a bachelor’s degree in law. Some graduates could immediately provide valuable legal services that did not require advanced coursework or considerable experience. Other graduates could complete an accelerated law school program in much less than three years, as occurs in Europe.

Deregulation seeks to increase competition for and alternatives to incumbent suppliers, not to prohibit their existence. So, traditional three-year law schools would continue to exist, and the ABA could continue to accredit law schools, as could any other accrediting institution that develops. The competition from alternative legal education programs would force traditional law schools to reduce their tuition. As a result, more graduates would be less encumbered by debt and more likely to pursue a career in public-interest law.

Entry deregulation would allow any individual to offer legal services without requiring them to obtain a specific legal education and to pass a state bar examination. Again, individuals would be free to attend traditional ABA-accredited law schools, take bar examinations, and acquire any other form of certification. Deregulation would also allow any firm or corporation, including foreign entities, to provide legal services without being owned by lawyers.

Firms in other industries operate ethically as public corporations; the exclusion of corporations providing legal services has been justified on the unsubstantiated grounds that corporations would be conflicted between representing their shareholders and their clients. The evidence from Washington, DC, which permits an Alternative Business Structure with nonlawyer ownership of a law firm, does not indicate that nonlawyer owners have pressured lawyers into ethics violations.

In sum, deregulation would lead to a more heterogeneous supply of lawyers and more intense competition among incumbent law firms and new legal service entrants. New low-cost legal services would be offered, current legal services would be offered at lower prices, and leaders of the global legal service industry would pioneer adoption of technological innovations that further reduce costs and prices for many services.

Some object that deregulation is likely to increase the number of lawyers, which includes legal service providers without a JD from an ABA-accredited law school, when the United States already has too many lawyers. However, this objection fails to consider that the equilibrium of supply and demand determines the number of lawyers.

The current high prices for legal services that reduce demand and the barriers to legal practice that reduce supply suggest that 1.3 million US lawyers are too few, not too many, and help explain why the United States ranks below other countries in terms of the accessibility and affordability of civil legal services. By decreasing the price of legal services and increasing the supply of lawyers, albeit increasing the share of low-cost legal service providers, which, as noted, will be part of the legal profession, and those wishing to practice public-interest law, deregulation would benefit the public by increasing the equilibrium number of lawyers.

Other objections to deregulating the legal profession are based on either a lack of appreciation of deregulation’s likely effects or a misunderstanding of what deregulation means. Trouble at the Bar argues that in practice, ABA regulations and education requirements do little to improve the quality of legal services. Scholars continue to debate why ABA regulations and education requirements were even adopted. In any case, states did not quickly adopt them to improve the quality of legal services for an allegedly uninformed public. Indeed, state legislatures took decades to adopt ABA education requirements because many state legislators themselves were graduates of unaccredited law schools and they would have to admit that they were not qualified to practice law!

Market forces have created websites, such as Angie’s List and Yelp, as well as social media platforms, which can accurately inform consumers about the quality, reputation, and performance of a broad range of service providers. Similar websites, such as AVVO and Martindale-Hubble, currently exist for lawyers. Others would proliferate, offering even more detailed information about legal service providers for a larger, more discerning, and more heterogenous volume of consumers.

Critics also assert that deregulation of lawyers is tantamount to advocating that doctors should not have to go to medical school, complete residency training, and obtain a license to practice medicine. As noted, no one would have to hire a lawyer who did not go to law school or pass a bar examination. Those who did would undoubtedly require credible evidence that the legal service provider was competent to perform the desired legal service.

Deregulation simply allows the market, not self-interested institutions, to determine the extent and type of legal education and credentials that are appropriate for a lawyer to perform specific services demanded by clients. Clearly, legal service providers who are assisting someone with a basic contract do not need to demonstrate the same level of competence, as indicated by educational degrees and professional accomplishments, as a lawyer representing a client before the Supreme Court or defending a homicide charge.

Finally, critics assert that many jobs, such as social workers, advocates, and paralegals, already exist to help alleviate legal problems, yet they ignore that most of the public is still not served by the legal profession. Deregulation would enable considerably more of the public to afford legal services at prices that, in general, would be markedly below current prices. Thus, the “law of demand” and new sources of supply would greatly expand access to justice.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3tYKnM1

via IFTTT

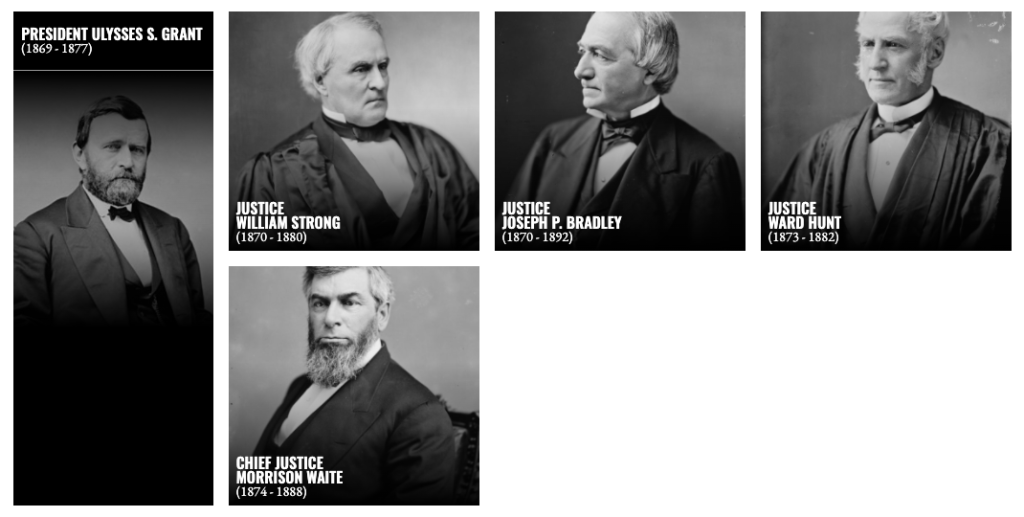

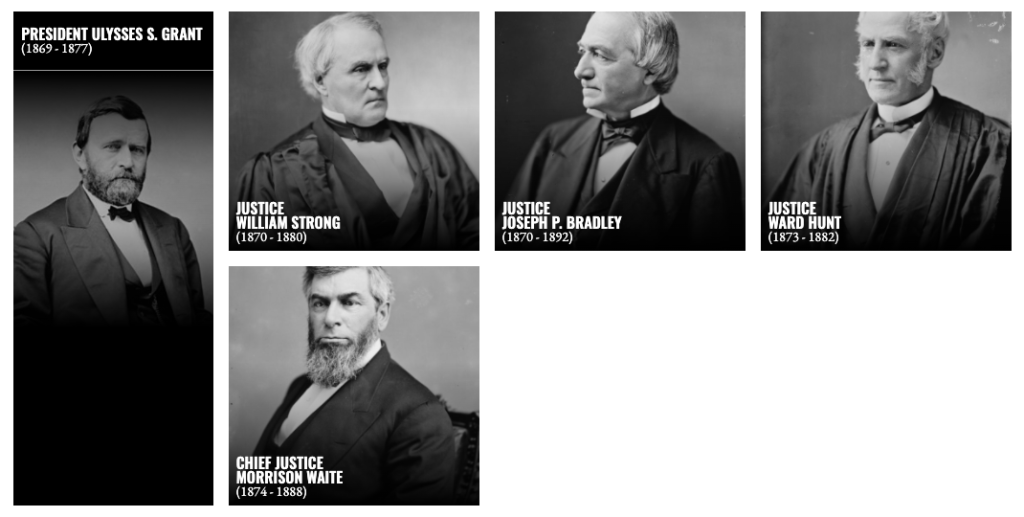

4/27/1822: President Ulysses S. Grant’s birthday. He would appoint four Justices to the Supreme Court: Chief Justice Waite, Justice Strong, Justice Bradley, and Justice Hunt.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3noDrp3

via IFTTT

4/27/1822: President Ulysses S. Grant’s birthday. He would appoint four Justices to the Supreme Court: Chief Justice Waite, Justice Strong, Justice Bradley, and Justice Hunt.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3noDrp3

via IFTTT