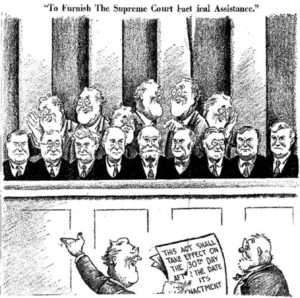

There’s an old saying: When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. For Congress, that hammer is the Small Business Administration (SBA). And every economic crisis is a nail.

Whenever the country is hit by a hurricane, an earthquake, or a terrorist attack, the government instructs the owners of small businesses that have been hurt to turn to the SBA for help. The agency was originally conceived in 1953 to provide guidance and aid to small businesses. Today, its mission statement also includes efforts “to preserve free competitive enterprise and to maintain and strengthen the overall economy of our nation.” But in recent decades, it has become the federal government’s all-purpose tool for promoting economic recovery.

Unfortunately, the agency has a long history of responding to crises chiefly with a mix of ineptitude, bureaucratic sloth, and cronyism—most spectacularly in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The current crisis is no exception.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, millions of firms were put out of business. By the middle of April, nearly 17 million people had filed for unemployment. Retail sales for the month of March fell 8.7 percent from February, the biggest single-month drop in the 30-year history of tracking. Analysts universally expected that the following month would be even worse.

And so, faced with an unprecedented economic downturn, Congress got out its hammer. The SBA was once again asked to dole out hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of federal loans and grants meant to prop up the economy during what looked to be the worst recession in a generation or longer.

Despite the agency’s longstanding, prominent role in the federal government’s economic recovery portfolio, there’s little reason to believe it will be successful in this case—and it may hurt more than it helps. For decades, the SBA has shown itself consistently unable to hit the nails placed before it. And as coronavirus relief efforts ramped up this spring, the agency quickly began failing taxpayers, small-businesses owners, and the nation’s economy, just when the country needed help the most.

$350 Billion Worth of Failure

In normal times, the SBA mostly exists to extend publicly guaranteed loans to companies that can’t find credit elsewhere. But these are far from normal times.

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the globe, U.S. states ordered lockdowns in hopes of slowing viral transmission. The national economy was put into a figurative coma.

In March, Congress stepped in with life support in the form of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, a $2.2 trillion spending program. Among its major provisions was $349 billion for small-business loans to cover qualified payroll costs, rent, utilities, and interest on debt obligations, later topped up with more than $300 billion in additional funds. That money was, of course, to be administered by the SBA.

There were two main pieces to the small-business relief part of the bill.

First, Congress directed the SBA to distribute $10 billion in disaster loans to businesses through an expansion of its Economic Injury Disaster Loan program (EIDL). Each eligible company could get a loan of up to $2 million, with the first $10,000 distributed as a grant—essentially an advance—within three days of its application to an SBA-qualified lender. In addition, a business could apply for an express bridge loan of up to $25,000 while waiting for the larger EIDL loan to come through.

The second piece was called the Payroll Protection Program (PPP), which tasked the SBA with issuing another $349 billion in loans to small businesses through an extension of its flagship 7(a) loan program. Low-interest-rate loans granted under the PPP will be forgiven in full—making them grants from the government in essence—under two conditions: 75 percent of the loan must cover the borrower’s payroll costs, and the loan must be used to keep workers on the payroll for an eight-week period after the loan is granted.

Businesses applying for both programs are already smacking face-first into an array of bureaucratic complications, from processing delays to unexpected changes in loan limits. Just a few weeks in—at a time when huge portions of the economy are desperately looking to the agency for assistance—the SBA’s administration of the PPP and EIDL looks incompetent at very best.

The first reason for that is scale. The SBA has to handle a very large number of requests in a very short period of time, something it’s wildly ill-equipped to do.

In a normal year, the agency makes about 60,000 loans totaling $30 billion. Of that amount, $2 billion are disaster loans and $23.2 billion are 7(a) loans. Under the CARES Act, the SBA had to process more than 10 times its annual load in the span of a few weeks, responding to each application within a three-day window, with very little guidance from Congress about how to proceed.

The demand for loans is intense because of how many businesses are eligible. The legislation uses the SBA definition of small business, meaning a firm with up to 500 employees. According to the Census Bureau, there were 5.6 million employer firms in the United States in 2016. Firms with fewer than 500 workers accounted for 99.7 percent of those businesses. As of 2016, there were an additional 24.8 million firms with no employees (think of a freelance artist who works for herself). That means that 99.9 percent of American firms are “small,” and 81 percent of them have no employees.

In practice, and for utterly arbitrary reasons, businesses such as commercial cleaners, home repair firms, and many franchises don’t seem to be eligible if the way they’re run and operated doesn’t fit the SBA’s preexisting model. Meanwhile, many big businesses are competing for these SBA loans. The legislation includes an exception to the 500-employee limit for hotel and restaurant chains. A recent Morgan Stanley report showed that more than $243.4 million of the total $349 billion had gone to publicly traded companies with thousands of employees. The Fiesta Restaurant Group, for example, employs more than 10,000 people and has a market cap of $189 million; it has received $10 million through the PPP.

Even if the SBA were the most competent agency in the country, it would be a spectacular challenge to identify, adjudicate, and disburse so many loans so quickly. The SBA, however, is not the most competent agency anywhere.

A Small-Business Nightmare

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina wiped out entire neighborhoods in the Mississippi Delta, leaving devastation in its tracks. Small businesses that experienced flood damage were encouraged to apply for SBA disaster loans to help them recover as fast as possible. For most applicants, the experience was another kind of disaster.

Take New Orleans resident Donna Colosimo, co-owner of Crescent Power System, a company that sells electrical power generation equipment to large industrial clients. In the aftermath of Katrina, the building that housed her business was submerged under 12 feet of water. “We lost everything,” she said in heart-wrenching July 2007 testimony before the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship. “We lost our inventory. We lost all parts of our business, including all business documentation that we had for 13 years.”

Colosimo and her husband tried to request a loan from the SBA and were forced to jump through a daunting number of bureaucratic hoops. It took weeks to figure out how to apply properly. They were asked multiple times to provide the agency with the same materials. “We were passed off to more than twenty different ‘loan officers’ who came and went like ghosts,” Colosimo wrote in her testimony, “and with each new voice at the other end of the phone; we pretty much had to start over.”

In October 2005, the Colosimos submitted their application. They then waited three more months, during which time they were told to provide more documents they didn’t have because they’d been destroyed in the storm. In January 2006, the couple was told over the phone that they were approved for a $250,000 loan that was supposed to be repaid in full in May 2007.

Unfortunately, they only received $10,000, which came in May 2006.

Colosimo made numerous attempts to obtain the rest of the loan money. She and her husband called the SBA repeatedly, each time speaking to someone different—someone who invariably knew nothing about their application and always asked for additional documents. They never received the rest of the funding. But a year later, the SBA insisted they were on the hook for the full $250,000.

In the meantime, the couple had upended their lives. As of February 2007, Colosimo testified, she had mortgaged her house twice. She begged the committee to “wake me up from this nightmare.” She eventually got things sorted out and her debts were eliminated, but not in time to reopen her business in New Orleans. She and her husband sold their home, liquidated their savings, and attempted to start fresh in Baton Rouge.

The Colosimos’ story isn’t an outlier. It’s one of hundreds of sad tales of SBA failure documented both by the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship and by reporters around the country following Katrina.

Two years after the hurricane, the SBA still faced a huge backlog of loan applications. By that time, the loan approval rate had dropped from an average of 60 percent for previous hurricanes to 33 percent, according to the agency’s inspector general. It turned out to be easier to decline, withdraw, or cancel an application than to approve it, so SBA staffers under deadline resorted to just that. Even when loans were approved, the agency sometimes failed to disburse the funds.

People inside the agency confirm these descriptions. In 2007, Gale Martin, an SBA loan officer working on Katrina disaster loans, testified before the same Senate committee about the process the agency was subjecting applicants to. She concluded her statement with these words: “I could go on, and on, for hours here, but the truth is that only the wealthy moved through the system easily. People with credit issues, who owed the government even a little bit of money, who had lost their documents, or who just moved around, would probably not be given a loan, and if they were, they would have to fight to keep it.”

The agency’s failure was so striking that in 2008, politicians on both sides of the aisle agreed to take steps to fix the problem. Rather than scale back the SBA’s lending activities and work to make it easier for the private sector to step in during the next disaster, though, Congress created three new programs meant to get loans to small businesses quickly…and gave the administration of these programs to the Small Business Administration.

In 2015, Politico reported that “since the new emergency lending programs were born, American small businesses have been hit by Hurricane Irene, Hurricane Sandy, and other disasters. And here’s how many loans the new programs have secured for small businesses in that time: Zero.”

Same bureaucrats; same disaster.

A Train Wreck in Every Imaginable Way

Fast-forward five years to the present disaster. No new reforms have been implemented. The SBA is as incompetent as ever. Yet this is the agency Congress tasked to help America’s desperate small businesses.

Unsurprisingly, the CARES Act’s SBA-related programs are already plagued by technical issues and an inability to process loans quickly. In an April letter to Administrator Jovita Carranza, four U.S. senators asked if the agency could deliver on the mandated requirement to make initial funding available within three days of a disaster loan application. Two weeks later, the SBA still hadn’t responded. But small-business owners were saying the agency wasn’t coming through.

Lyle Albaugh is the chief financial officer of Betsy Fisher, a high-end women’s clothing boutique in Washington, D.C. He applied for the SBA disaster relief loan on March 28. He notes that the application process was laborious, with a number of ambiguous questions he wasn’t sure how to answer. He was also required to provide Betsy Fisher’s 2018 tax return, its schedule of liabilities, and a personal financial statement. Yet after 11 days, he says, “I haven’t heard a word from the SBA. I don’t know if our application was accepted or when I’ll know anything about our status.”

In April, The Wall Street Journal reported that multiple business owners around the country were similarly in the dark regarding the status of their loans. They had applied and waited weeks. The SBA had responded with silence.

Meanwhile, some applicants who were lucky enough to be approved for disaster loans through their banks are now finding out that they will receive only a fraction of the funds they were promised. A New York Times report told the story of Deb Wood-Schade, the owner of a chiropractic wellness business in California who was approved for a loan of $25,000 by her bank in mid-March but later found out she would get only $8,300.

According to the Times, SBA loan officers told several applicants that EIDL disbursements would be capped at $15,000 instead of the $2 million originally announced. That amount is in addition to the $10,000 grant each small business and nonprofit is eligible to receive. If some loan funding has been disbursed, it is unclear whether the borrower can also ask for a $25,000 bridge loan as he or she waits for the rest.

Over 400 applicants told the Times that, despite the statutory requirement that the grants be processed quickly, they had received nothing 10–14 days after their applications were submitted. In addition, many business owners have been told by the SBA that they need at least 10 employees to get the full $10,000 grant, even though the legislation contains no such provision.

The PPP—the program meant to keep workers attached to the labor force by backstopping payrolls—isn’t functioning any better. To get one of those loans, the borrower must first apply through a bank. That bank in turn submits the application through an SBA portal for approval by the agency. But the portal often crashes, the paperwork requirements are onerous and subject to change without notice, and interest rates have been shifting in real time, driven by Treasury Department policy. Lenders, meanwhile, sometimes impose their own requirements—such as demanding that the business have an existing loan with the bank.

In just about every imaginable way, the PPP rollout has been a train wreck. It’s obvious that the program suffers from design flaws that need to be addressed by Congress.

Once again, Albaugh’s experience is instructive. He applied to the PPP on April 3 via another confusing application process that required even more forms. “All of these applications require a lot of gathering of documents, getting signatures, and scanning,” he says. “It seems trivial, but it’s time-consuming.”

He went to his bank, a national chain where he’d had a commercial account for decades. He was told he would have to apply online—but the site wasn’t yet accepting applications. A few days later, the bank posted a message saying it was “working with the Small Business Administration to provide relief to Small Business owners” but that it was still “not yet able to accept applications for the Paycheck Protection Program.”

Eventually, Albaugh was able to submit his application—at which point he found that stringent limits had been placed on the amount he could borrow. It wasn’t clear to him whether this was a bank rule or an SBA regulation. The lack of clarity around the actual conditions of the program is an additional hurdle small-business owners have to deal with.

Every bank is swamped. The Washington Post reported that less than 10 days after the PPP was authorized, Bank of America had already received 178,000 applications from firms seeking $32.9 billion in loans. Wells Fargo had reached the $10 billion cap it had set for loans under the program.

Albaugh says he’s seen reports “about hundreds of thousands of dollars in funds being disbursed, with an average disbursement over $100,000. Who’s getting these loans and how? I have no idea. Will the funds be used up before we’re even permitted to apply?”

By the middle of April, the small-business funding authorized by the law had been exhausted. Many of the recipients turned out to be the large hotel and restaurant chains that had been granted exceptions to the 500-person limit. Restaurant chains like Ruth’s Chris and Potbelly received tens of millions. Controversy over the loans was significant enough that Shake Shack, a popular burger chain, returned a $10 million loan.

The program appeared to be intentionally skewed toward larger businesses. Since the funding amounts are based on average monthly payroll, it takes a large number of employees to be eligible for the maximum loan. A company’s payroll would have to be at least $48 million, in fact, for it to get $10 million under the program. That’s a fairly big small business. Thus, it’s likely that most of the money will end up going to larger firms.

At the same time, no one knows how many loans have been approved or how many firms have received funds. In fact, many banks report lacking the proper SBA paperwork to finish the application process and turn the money over to businesses. In late April, Congress passed a $484 billion follow-up to the CARES Act, adding $320 billion to the small-business payroll protection fund and $60 billion to the disaster relief program. Yet even after the top-up, The Washington Post reported that the SBA was secretly capping disaster loan amounts and that the program faced a backlog of millions of applications.

Worse yet: As hard as they are to come by, these loans may not make much of a difference for the companies. “Due to the effect of the total shutdown, loans are of very little help to a healthy business,” writes Albaugh in an email. “The total losses that Betsy Fisher is suffering aren’t even close to being made whole with loans. The loan just spreads out the pain over the payment period.”

More Funding For An Incompetent Agency

Disasters are inevitable. But even the ones we know are coming can be difficult to predict in their precise details.

In late summer, hurricanes form overnight and can hit at any point along the coasts. They shift course at the last minute, and their strength can change quickly. We know that hurricanes will hit us again—somehow, someplace—but no one can say with certainty when, where, or with what force. Over a long enough timeline, terrorist attacks of some sort may be unavoidable. Earthquakes and tornadoes don’t exactly make calendar appointments.

There is, indeed, a lot of unavoidable uncertainty surrounding natural disasters and other public emergencies. But amid this uncertainty, one tower of inevitability looms: The Small Business Administration will always, always fail to help the small businesses that it was designed to support.

The SBA should have been abolished decades ago. The agency’s nondisaster programs address no genuine market failures, as evidenced by the fact that such SBA financing is minuscule compared to what small businesses receive from banks and other agents in private capital markets. Yet these programs impose net costs on the economy, as do most government loans, by passing the bill to future taxpayers while shifting resources toward government-chosen businesses at the expense of other firms.

On the disaster side, the SBA’s complete ineptitude during and after each emergency should convince politicians that it’s time to intervene. Congress doesn’t have the power to stop hurricanes. But it can stop the predictable disaster that is the SBA’s systematic, catastrophic bungling of its mandate.

Shuttering this agency would clear a path for the private sector to step in with new financing options for small businesses. Instead, lawmakers continue to encourage suffering business owners to use the agency by promising free money and cheap loans.

Despite countless warning signs that the SBA was botching its responsibilities under the CARES Act, the bipartisan consensus in the weeks after that law passed was that the next step should be to provide the agency with hundreds of billions of dollars in additional funding. Congress, as ever, was responding to an economic calamity with the only tool it seems to know how to use. But throwing more money at the program without fixing its fundamental flaws is yet another disaster waiting to happen.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3dZgfrS

via IFTTT