Katie Haun has one of bitcoin’s most improbable conversion stories. As an attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice, she prosecuted the two corrupt federal agents working the Silk Road case and created the federal government’s first cryptocurrency task force. “I’m the prosecutor who helped put some of the earliest bitcoin criminals in jail,” she boasted in a 2018 speech.

But while learning about bitcoin as a crime fighter, it dawned on her “how profoundly this technology could change how we do all sorts of things.” Haun is now a general partner at the venture capital fund Andreessen Horowitz, or a16z, where she co-leads its crypto funds with over $350 million raised since 2018. The firm is betting on blockchain as a new computing platform that will, among other things, create a decentralized financial system and fulfill the web’s original promise as an open network controlled by its users.

Blockchain computing “feels like the early days of the internet, web 2.0, or smartphones all over again,” according to a16z’s crypto thesis. Haun also sits on the board of the nonprofit organization overseeing Facebook’s cryptocurrency project Libra. At a 2019 congressional hearing, David Marcus, head of the company’s blockchain group, assured lawmakers, “Let me be clear and unambiguous: Facebook will not offer the Libra digital currency until we have fully addressed regulators’ concerns and received appropriate approvals.”

In their embrace of regulation, Haun and Marcus are at one extreme of the cryptocurrency community; on the other end, are the so-called bitcoin maximalists who have a name for projects like Libra: “shitcoin.”

“I would not be interested in bitcoin if governments didn’t want to ban it,” the software developer Pierre Rochard tweeted in 2017.

In a December 2019 essay titled “Cryptocurrency Is Most Useful for Breaking Laws and Social Constructs, Open Money Initiative Founder Jill Carlson wrote that cryptocurrency wasn’t designed to solve “mainstream problems.” It’s a tool used by “freedom fighters and terrorists, by journalists and dissidents, by scammers and black market dealers,” by “sex workers” or people “procuring drugs on the internet”—the type of person Katie Haun once worked to put in jail. Bitcoin maximalists, like Rochard, believe that governments will eventually attempt to ban bitcoin because it’s destined to replace fiat money, which will, among other things, eliminate their power to print money to finance the welfare-warfare state.

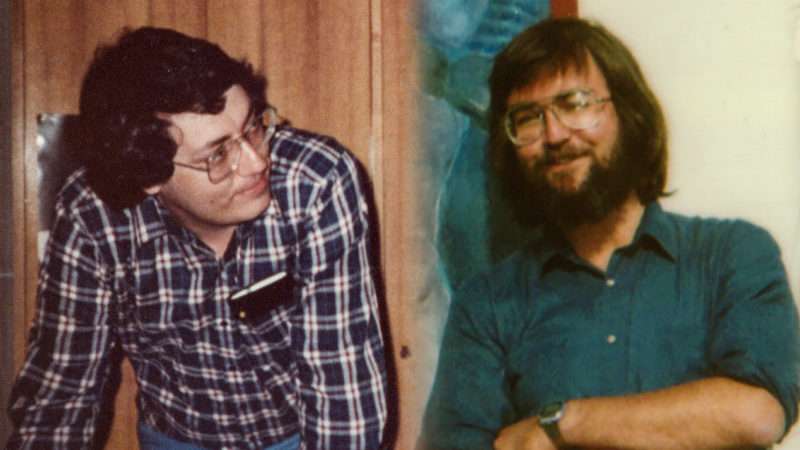

The divide over whether this technology is a tool for changing society by working within the system or by disrupting it from the outside predates the invention of bitcoin by a few decades. It traces back to a 1987 debate between the physicist Timothy C. May and the economist and entrepreneur Phil Salin, two early internet visionaries, whose difference of opinion laid the groundwork for the “cypherpunk” movement—a community of computer scientists, mathematicians, hackers, and avid science fiction readers whose work and writings influenced the creation of bitcoin, WikiLeaks, Tor, BitTorrent, and more. (Reason is publishing a four-part documentary series on the cypherpunk movement. The first two installments are available here and here.)

The bitcoin maximalists often use the “shitcoin” moniker to refer to cryptocurrency projects that are outright scams, technologically flawed, or cheap imitations of Satoshi Nakamoto’s invention, when in reality the world only needs one currency. Bitcoin, they maintain, is best understood as sound money, and Silicon Valley’s infatuation with “blockchain technology” is “a great example of ‘cargo cult science,'” as the economist Saifedean Ammous wrote in The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking.

But the community’s divide is also partly rooted in a disagreement over whether cryptocurrency is essentially a technology of resistance that derives value from being impervious to government interference and control, or whether it’s a tool for transforming society from within, in which case government regulation won’t sink the entire enterprise. A careful look at the debate that started with May and Salin in the 1980s helps us understand the best arguments of both sides.

BlackNet: ‘A Technological Means of Undermining all Governments’

In 1987, before the launch of the World Wide Web, May and Salin were part of a small community of West Coast science fiction–obsessed technologists mulling the implications of a decentralized, global information network running on personal computers. It was clear to May and Salin that the internet would remake the world, but they disagreed on what kind of software would serve as the linchpin.

Salin saw technology as a way to gradually drive down the transaction costs that impede human activity, making it feasible to interact in ways that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive. “I’m interested in how to lower costs,” Salin told Reason in 1984. “The Austrian [School of Economics] insight is that any industry run as a planned economy for any time should be fertile ground for an entrepreneur.”

In 1986, he started the American Information Exchange, or AMIX, one of the first e-commerce startups. Salin, whose intellectual hero was the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, envisioned AMIX as a global marketplace for the buying and selling of local expertise that would enhance human cooperation and gradually replace central planning.

In a 1991 essay, Salin envisioned a “fluid, transaction-oriented market system, with two-way feedback” that could result in “crowding out monolithic, mostly government bureaucracies.” The same language could be applied to many projects in the modern cryptocurrency space. Facebook’s Libra, for example, promises to use blockchain technology to move money around the world in a manner that’s “as easy and cost-effective” as “sending a message or sharing a photo.” The project’s backers maintain that enabling “frictionless payments” for the 1.7 billion people around the world without access to banking will do wonders for alleviating poverty. Those frictions are mostly created by government regulation; what’s implicit in Facebook’s pitch is that those rules will be gradually crowded out, though not overthrown.

After being introduced to Salin by his friend Chip Morningstar, a computer scientist, in December 1987, May drove out to Redwood City, California to meet Salin and hear his pitch for AMIX. He grasped the idea immediately, but it bored him. “People aren’t going to be selling meaningless stuff, like surfboard recommendations,” May recalled telling Salin.

May didn’t think AMIX was a scam, like many modern cryptocurrency ventures that earn that descriptor shitcoin. But he was interested in upending society and didn’t see how AMIX would have much of an impact.

May suggested to Salin that he reconceive of the project as an anonymous platform for selling company trade secrets, “such as plans for that B-1 Bomber or a process for a technology.” In a thought experiment, May later called his idea “BlackNet,” writing in a pretend advertisement for the service that it would turn “nation-states, export laws, patent laws, national security considerations and the like” into “relics of the pre-cyberspace era.”

In a series of personal notes following his meeting with Salin, which May shared with Reason prior to his death in 2018, he mused that BlackNet was a “technological means of undermining all governments.” Though some might say that “‘it won’t be allowed to happen’ technology would ‘probably make it inevitable,'” he wrote.

May’s ideas about BlackNet evolved over the years. In 1986, a friend had given him a photocopy of Vernor Vinge’s 1981 novella True Names, in which hackers inhabit a virtual world called the “Other Plane” where the government can’t decipher their real identities. It had a big impact on May, who melded the “Other Plane” with “Galt’s Gulch” from Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, which was a safe haven for rational and productive people protected from government coercion and taxation by an invisible shield. Instead of the Colorado mountains, May’s cyberspace Galt’s Gulch would exist on the internet, with cryptography providing protective cover.

“Just as the technology of printing altered and reduced the power of medieval guilds and the social power structure,” May wrote in his 1988 manifesto, “so too will cryptologic methods fundamentally alter the nature of corporations and of government interference in economic transactions.”

Bitcoin isn’t BlackNet or a Galt’s Gulch in Cyberspace—it’s a decentralized form of non-governmental money. But it’s designed to be impervious to outside tampering so that the government can’t destroy it or undermine its value, and is roughly in keeping with May’s vision of an unstoppable technology. “The nature of sound money…lies precisely in the fact that no human is able to control it,” Ammous wrote in The Bitcoin Standard. Bitcoin “exist[s] orthogonally to the law; there is virtually nothing that any government authority can do to affect or alter [its] operation.”

The American Information Exchange: Exploiting the ‘Grey Areas’

The computer scientist E. Dean Tribble, who worked with Salin at AMIX, calls May “the shock jock” of the cypherpunk movement. “BlackNet is not a goal,” he says. “BlackNet is a negative consequence.”

Morningstar, the pioneering computer scientist who Salin hired to oversee the building of AMIX, recalls his boss’s skepticism of May’s ideas about escaping “the strictures and dysfunction of the mainstream-governed world.” The establishment “has had a long history of confronting new challenges and somehow having its way.”

Salin died of cancer in 1991 at age 41. His friend and colleague Mark S. Miller, a computer scientist, would flesh out the case that technology impacts society by gradually transforming it from within. Miller drew an analogy to a genetic takeover in biology, in which an alternate way of doing things slowly takes the place of an existing paradigm.

Projects like AMIX, which was centrally controlled by a company, didn’t need to be completely “incorruptible” to have an impact because of all the grey areas where regulation doesn’t apply. Permissionless innovation pushes society in the direction of more freedom and decentralization. For example, “when people started doing credit card transactions over the internet, nobody knew if it was legal,” Miller tells Reason, “but they just started doing it.”

Miller doesn’t consider Libra to be a worthless project despite Marcus’ commitment to cooperate with regulators. Once it starts operating, Miller says, there could still be experimentation happening “at the margins.” There could also be gateways to “trading between Libra and something permissionless,” which would help expand the cryptocurrency space.

Miller’s writings have often focused on how rules baked into computer code could replace aspects of the legal system. Along with K. Eric Drexler, the father of nanotechnology, he co-authored a series of papers applying economic insights to software design, which influenced the work of the computer scientist, legal scholar, and early cypherpunk Nick Szabo.

It was Szabo who coined the term “smart contracts“—self-executing arrangements written in code, and a common feature in today’s cryptocurrency projects. Szabo analogized his concept to a vending machine: A buyer drops in a coin and a machine provides the candy bar. “The fundamental logic here is automating ‘if-this-then-that’ on a self-executing basis with finality,” Szabo wrote. He also offered the example of a smart contract for auto repossession: “If the owner fails to make payments, the smart contract invokes the lien protocol, which returns control of the car keys to the bank.”

A divide in the community over the definition of a smart contract also relates back to Salin’s debate with May. Do smart contracts have to be shielded from third-party interference to be worthy of the name? What if a government regulator has the power to stick a hand into the metaphorical vending machine to stop the candy bar from dropping into the slot? Does that undermine the purpose of smart contracts?

Miller and Morningstar consider AMIX to be “possibly the first smart-contracting system ever created” because it used software to mediate transactions between two parties. Deals on AMIX combined a written component, like a traditional contract, and a self-executing component: once a buyer and seller agreed on a price for a service, payment would be carried out by software. If there was a dispute, it would be resolved by humans.

AMIX software ran on a central server, meaning the company or a government regulator could theoretically interfere with the execution of a sale. According to Morningstar and Miller, the potential for interference doesn’t undermine the purpose of the smart contract.

“A smart contract that trusts a third party removes the killer feature of trustlessness,” wrote Jimmy Song, a bitcoin maximalist and influential figure in the space, in his 2018 essay, “The Truth About Smart Contracts.”

Song applies his critique to a popular crypto business model, which Miller has also written about: using smart contracts to trade physical assets, such as land. Countries like Sweden and Georgia have explored operating a land registry that uses blockchains and smart contracts. Szabo explored this idea in a 1998 paper that predated blockchains and bitcoin titled “Secure Property Titles with Owner Authority.“

Physical assets are traded with smart contracts through what’s called tokenization. A property is assigned a digital tag with a corresponding private key. A seller uses that key to transfer ownership to the buyer, much like a bitcoin transaction. The record of ownership is encoded into a blockchain, which is a type of shared public database, so all parties know that it hasn’t been corrupted.

“There is an intractable problem in linking a digital to a physical asset whether it be fruit, cars or houses,” Song wrote. It “suffers from the same trust problem as normal contracts” because “physical assets are regulated by the jurisdiction you happen to be in.”

So if a judge refuses to honor that tokenized transaction, or a conqueror shows up at the door with an army, the smart contract will have accomplished nothing. “Ownership of the token cannot have dependencies outside of the smart contracting platform,” wrote Song, who sees smart contracts as useful only in systems like bitcoin, where the digital token itself holds value.

Miller offered a rebuttal to this argument in a lecture titled, “Computer Security as the Future of Law” in 1997, predating Song’s article by 21 years. He laid out a vision for a gradual takeover of the existing law by smart contracts. We live in a world where different systems of rules are layered on top of each other, he explained. When Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky played chess, they had to abide by the rules of the board, dictating, for example, that bishops can only move diagonally. They were simultaneously governed by another set of rules because the two men were “biological creatures…embedded in physics.” A Macintosh operating system is another example of a system that imposes a set of rules spelled out in software embedded in another set of rules—i.e., legal strictures, physics, and biology.

The rules on these different layers impact each other. For example, the physical world and the legal world have distinct sets of rules, but in legal disputes “physical possession has extraordinary influence in the actual outcome of the dispute, even if abstractly the law would have it otherwise.” If an object that belongs to you is in another person’s house, taking them to court to get possession of that object is rarely worth the hassle.

AMIX integrated computer-mediated contracts and human negotiated contracts. It’s true that humans, including government regulators, could override a transaction on AMIX, but for practical reasons that was unlikely to occur very often. Therefore, smart contracts on AMIX would have fulfilled their purpose in the vast majority of cases by reducing transaction costs with computer-mediated contracting.

Miller elaborated on this idea in a discussion of land registries in “The Digital Path: Smart Contracts and the Third World,” a 2003 paper that he co-wrote with Marc Stiegler. It acknowledges that a smart contracting system, “unlike government-based title transfer,” won’t be “backed by a coercive enforcement apparatus,” but the authors proposed various add ons to make it more likely that participants will “treat these titles as legitimate claims,” including a community rating system, and video contracting—an idea first proposed by Szabo—in which a conversation is recorded testifying to the validity of the arrangement in question.

These tools don’t guarantee that governments will honor and enforce smart contracts, but there’s also a high cost to ignoring them. Szabo summed up this idea best in his 1998 paper: “While thugs can still take physical property by force, the continued existence of correct ownership records will remain a thorn in the side of usurping claimants.”

Miller, Morningtar, and Tribble, who were involved with AMIX in the 1980s, have come together once again to try and make good on Salin’s vision. Miller and Tribble co-founded a startup called Agoric, which seeks to build a secure smart-contracting system that could serve as the backbone of a more decentralized internet, luring some high-level computer scientists away from comfortable jobs at the biggest software companies in Silicon Valley.

May passed away suddenly in 2018 at age 66. In the months leading up to his death, he was feeling disgusted with the proliferation of cryptocurrency conferences and regulated blockchain ventures. “I think Satoshi would barf,” he told CoinDesk. “Attempts to be ‘regulatory-friendly’ will likely kill the main uses for cryptocurrencies, which are NOT just ‘another form of PayPal or Visa.'”

In May’s view, society still faced a “fork in the road…freedom vs. permissioned and centralized systems.” There are no grey areas.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3lUnKUI

via IFTTT