9/16/1787: The Constitutional Convention finalizes Constitution.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2GZDd6A

via IFTTT

another site

9/16/1787: The Constitutional Convention finalizes Constitution.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2GZDd6A

via IFTTT

Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, by Tara Isabella Burton, PublicAffairs, 320 pages, $28

Over the last 15 years, two growing groups of people have been drifting away from traditional organized religion. One is the “Nones,” the 25 or so percent of American adults who consider themselves religiously unaffiliated. The other—which overlaps with the first—is the “Remixed,” Tara Isabella Burton’s term for people who blend traditional faiths with “personal, intuitional spirituality.”

Burton, a journalist with a doctorate in theology, discusses both cohorts in Strange Rites, a book about Americans who reject traditional religious dogmas and labels. These people are often churchless and sometimes godless. But that doesn’t mean they’ve rejected religion. Many of them simply worship different things.

What counts as religion is crucial. Are erstwhile presidential hopeful Marianne Williamson’s Oprah-endorsed self-help books religious texts? What about the life-hacking, mushroom-coffee-guzzling, four-hour–everything works of productivity guru Tim Ferriss?

For Burton’s purposes, religion consists of meaning, purpose, community, and ritual. By meaning, she means some way of demarcating the line between good and evil, coupled with a sense of what life is fundamentally about. By purpose, she means your own role within that meaning. By community, she means the people you rely on. And by ritual, she means how you and your group mark the passage of time together, with acts of mourning, celebration, coming of age, penitence, and commitment to the faith.

Within that framework, Burton finds religion among SoulCycle obsessives, social justice warriors, far-right atavists, kink and polyamory communities, and Silicon Valley techno-utopians. As with the faith traditions of yore, they all have something that provides them with meaning, purpose, community, and ritual.

This rise in choice is good for personal autonomy, but these new religions tend to be thin on community building. Burton’s thoughtful analysis bolsters the sense that these young, syncretic religions might be less durable than traditional communities of faith.

One of the chief differences between today’s remixed faiths and conventional institutionalized religions is the premium the former place on personal experience, which is often considered irrefutable.

Wellness culture, from SoulCycle to meditation apps to the Goop empire, relies on this exalted interiority. “It’s a theology, fundamentally, of division: the authentic, intuitional self—both body and soul—and the artificial, malevolent forces of society, rules, and expectations,” Burton writes. “Our sins, if they exist at all, lie in insufficient self-attention or self-care.” Techno-utopians, meanwhile, are interested in how biohacking can maximize and make up for the limitations of the natural self. Occultists sometimes marry components of wellness culture with explicitly political messaging: Burton describes occult literature on how “to cast a spell to ensure resilience after a long day of protesting” and why curses can be “the only avenue for justice available to the downtrodden.”

The social justice community has a different take on the politics of personal experience, one built more on self-effacement than on self-exaltation. Its members, Burton argues, hold “two seemingly contradictory ideas about the self. The first is that, insofar as we are marginalized, society has warped our fundamental goodness. We have some form of a desirable, natural state that an unjust society has taken from us.” But that exists alongside a belief that the “inherent self does not actually exist…our entire identities are so inextricably linked to our social place that we have no selves outside them.”

An absence of established dogma, hierarchy, and tradition can be freeing. Burton details the origins of kink culture in the late-1970s Golden Age of Leather, when many gays were still closeted. “Prior to this subculture’s shattering encounter with HIV,” the historian Guy Baldwin once wrote, “a gay man in search of his kinky identity and fulfillment would eventually cross a threshold into leather space (leather bars, gay motorcycle events, special parties) for the first time….To think of it as merely sexual is to miss the scope of it entirely.”

Burton describes the old order as “concentric circles of communal obligation” in which a married couple was the core, aided by its extended family and helped along by a neighborhood and church. Now the rules have changed. Weddings and funerals, freed from traditional formats, have little preordained structure. “You’re on your own. You have to figure it out, explain it to people, rent the space, find people, figure out how to write up your own program,” the sociologist Phil Zuckerman tells Burton.

When a New York social worker’s queer husband died, Burton writes, she “declined to attend the memorial service hosted by her husband’s family in his hometown,” because they were “born-again Christians, uncomfortable with both her husband’s sexuality and his interest in the occult.” Instead, Burton elaborated in Vox, “a Jewish friend recited the Mourners’ Kaddish. The group told stories—some reverential, some ‘bawdy’—that reflected all aspects of Jon’s personality. They played an orchestral rendition of the theme song to Legend of Zelda, Jon’s favorite video game.”

Burton sees consent as the “foundational basis” for kink communities, and she extrapolates that this speaks to a deeper worldview: “We are totally free beings, beholden to nobody but ourselves. Exerting that freedom, furthermore, is at the core of what it means to pursue the good. Our choices, in this model, both define and liberate us.” This dual emphasis on consent and choice can be important for groups that were not previously able to explore the contours of their freedom in the light of day.

But having fewer cohesive principles comes at a cost. A focus on personal experience doesn’t always work against building community—shared experience can be a powerful social glue—but it often does. In none of these belief systems is there an explicit call to always love your neighbor as you love yourself, or to care for the poor and downtrodden regardless of their sins and failings, or to work to conquer your own vanity and self-indulgence. The social justice community comes closest, but it does not extend its gospel of dignity to those who engage in problematic behavior.

The bespoke communities of the Remixed and the Nones often have little room for children, the elderly, or people with severe disabilities. Sometimes this exclusivity is accidental, other times intentional: Many in the kink and poly communities disapprove of monogamy, while some members of the occult, social justice, and wellness cultures find little help navigating the hardships of parenthood, if only because they’re severely outnumbered by the childless.

At their best, traditional faiths bring those groups in. A Christianity Today headline from 2018 reads, “My Son’s Down Syndrome Showed Me the Real Imago Dei.” The Book of Numbers (and accompanying midrash) make clear the importance of honoring elders within the Jewish community. Some of the goodness of these traditions stems from the fact that the Bible communicates a profound message about human worth. That might be part of why it’s been such a durable document, attracting adherents over centuries.

The Nones and the Remixed may be more common than they used to be, but they are not new. Strange Rites covers plenty of precursors, from the Oneida Community’s mid–19th century free-love experiment to the Social Gospel movement of the Progressive Era and its influence on midcentury Protestantism, which “did not stress dogma or, in many cases, even metaphysical truth, but rather a utopian vision of what a truly ecumenical, social-justice-focused Christian world would look like.” Early American colonists supplemented their formal faiths with fortune telling and astrology; one could call them remixed too.

When Strange Rites falters, it’s because Burton tackles too much. She attempts to conduct a full autopsy of groups ranging from far-right “incels” to biohackers in just 250 pages, laying out the relevant history as well. Inevitably, some points are left underdeveloped. She raises the issue of some of these subcultures’ lack of socioeconomic and ethnic diversity, for example, but hardly digs into the implications.

But it’s a rich book, one that gave me insight not just into my society but into myself. I used to be an atheist, today am a Christian, and am certain the evangelical church that I currently attend won’t be my final spiritual landing spot. An Eastern Orthodox depiction of Jesus hangs in my home, I’ve been deepening my understanding of scripture by learning about the Jewish Sabbath, and I don’t think weed or psychedelics should be verboten for believers. In other words, I’m remixed. But that syncretic faith has been a gateway drug to something more like traditional religion, drawing me to a place of sturdier Christian belief and more durable community. And I don’t think I’m the only one who can say that.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2FxF81O

via IFTTT

Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, by Tara Isabella Burton, PublicAffairs, 320 pages, $28

Over the last 15 years, two growing groups of people have been drifting away from traditional organized religion. One is the “Nones,” the 25 or so percent of American adults who consider themselves religiously unaffiliated. The other—which overlaps with the first—is the “Remixed,” Tara Isabella Burton’s term for people who blend traditional faiths with “personal, intuitional spirituality.”

Burton, a journalist with a doctorate in theology, discusses both cohorts in Strange Rites, a book about Americans who reject traditional religious dogmas and labels. These people are often churchless and sometimes godless. But that doesn’t mean they’ve rejected religion. Many of them simply worship different things.

What counts as religion is crucial. Are erstwhile presidential hopeful Marianne Williamson’s Oprah-endorsed self-help books religious texts? What about the life-hacking, mushroom-coffee-guzzling, four-hour–everything works of productivity guru Tim Ferriss?

For Burton’s purposes, religion consists of meaning, purpose, community, and ritual. By meaning, she means some way of demarcating the line between good and evil, coupled with a sense of what life is fundamentally about. By purpose, she means your own role within that meaning. By community, she means the people you rely on. And by ritual, she means how you and your group mark the passage of time together, with acts of mourning, celebration, coming of age, penitence, and commitment to the faith.

Within that framework, Burton finds religion among SoulCycle obsessives, social justice warriors, far-right atavists, kink and polyamory communities, and Silicon Valley techno-utopians. As with the faith traditions of yore, they all have something that provides them with meaning, purpose, community, and ritual.

This rise in choice is good for personal autonomy, but these new religions tend to be thin on community building. Burton’s thoughtful analysis bolsters the sense that these young, syncretic religions might be less durable than traditional communities of faith.

One of the chief differences between today’s remixed faiths and conventional institutionalized religions is the premium the former place on personal experience, which is often considered irrefutable.

Wellness culture, from SoulCycle to meditation apps to the Goop empire, relies on this exalted interiority. “It’s a theology, fundamentally, of division: the authentic, intuitional self—both body and soul—and the artificial, malevolent forces of society, rules, and expectations,” Burton writes. “Our sins, if they exist at all, lie in insufficient self-attention or self-care.” Techno-utopians, meanwhile, are interested in how biohacking can maximize and make up for the limitations of the natural self. Occultists sometimes marry components of wellness culture with explicitly political messaging: Burton describes occult literature on how “to cast a spell to ensure resilience after a long day of protesting” and why curses can be “the only avenue for justice available to the downtrodden.”

The social justice community has a different take on the politics of personal experience, one built more on self-effacement than on self-exaltation. Its members, Burton argues, hold “two seemingly contradictory ideas about the self. The first is that, insofar as we are marginalized, society has warped our fundamental goodness. We have some form of a desirable, natural state that an unjust society has taken from us.” But that exists alongside a belief that the “inherent self does not actually exist…our entire identities are so inextricably linked to our social place that we have no selves outside them.”

An absence of established dogma, hierarchy, and tradition can be freeing. Burton details the origins of kink culture in the late-1970s Golden Age of Leather, when many gays were still closeted. “Prior to this subculture’s shattering encounter with HIV,” the historian Guy Baldwin once wrote, “a gay man in search of his kinky identity and fulfillment would eventually cross a threshold into leather space (leather bars, gay motorcycle events, special parties) for the first time….To think of it as merely sexual is to miss the scope of it entirely.”

Burton describes the old order as “concentric circles of communal obligation” in which a married couple was the core, aided by its extended family and helped along by a neighborhood and church. Now the rules have changed. Weddings and funerals, freed from traditional formats, have little preordained structure. “You’re on your own. You have to figure it out, explain it to people, rent the space, find people, figure out how to write up your own program,” the sociologist Phil Zuckerman tells Burton.

When a New York social worker’s queer husband died, Burton writes, she “declined to attend the memorial service hosted by her husband’s family in his hometown,” because they were “born-again Christians, uncomfortable with both her husband’s sexuality and his interest in the occult.” Instead, Burton elaborated in Vox, “a Jewish friend recited the Mourners’ Kaddish. The group told stories—some reverential, some ‘bawdy’—that reflected all aspects of Jon’s personality. They played an orchestral rendition of the theme song to Legend of Zelda, Jon’s favorite video game.”

Burton sees consent as the “foundational basis” for kink communities, and she extrapolates that this speaks to a deeper worldview: “We are totally free beings, beholden to nobody but ourselves. Exerting that freedom, furthermore, is at the core of what it means to pursue the good. Our choices, in this model, both define and liberate us.” This dual emphasis on consent and choice can be important for groups that were not previously able to explore the contours of their freedom in the light of day.

But having fewer cohesive principles comes at a cost. A focus on personal experience doesn’t always work against building community—shared experience can be a powerful social glue—but it often does. In none of these belief systems is there an explicit call to always love your neighbor as you love yourself, or to care for the poor and downtrodden regardless of their sins and failings, or to work to conquer your own vanity and self-indulgence. The social justice community comes closest, but it does not extend its gospel of dignity to those who engage in problematic behavior.

The bespoke communities of the Remixed and the Nones often have little room for children, the elderly, or people with severe disabilities. Sometimes this exclusivity is accidental, other times intentional: Many in the kink and poly communities disapprove of monogamy, while some members of the occult, social justice, and wellness cultures find little help navigating the hardships of parenthood, if only because they’re severely outnumbered by the childless.

At their best, traditional faiths bring those groups in. A Christianity Today headline from 2018 reads, “My Son’s Down Syndrome Showed Me the Real Imago Dei.” The Book of Numbers (and accompanying midrash) make clear the importance of honoring elders within the Jewish community. Some of the goodness of these traditions stems from the fact that the Bible communicates a profound message about human worth. That might be part of why it’s been such a durable document, attracting adherents over centuries.

The Nones and the Remixed may be more common than they used to be, but they are not new. Strange Rites covers plenty of precursors, from the Oneida Community’s mid–19th century free-love experiment to the Social Gospel movement of the Progressive Era and its influence on midcentury Protestantism, which “did not stress dogma or, in many cases, even metaphysical truth, but rather a utopian vision of what a truly ecumenical, social-justice-focused Christian world would look like.” Early American colonists supplemented their formal faiths with fortune telling and astrology; one could call them remixed too.

When Strange Rites falters, it’s because Burton tackles too much. She attempts to conduct a full autopsy of groups ranging from far-right “incels” to biohackers in just 250 pages, laying out the relevant history as well. Inevitably, some points are left underdeveloped. She raises the issue of some of these subcultures’ lack of socioeconomic and ethnic diversity, for example, but hardly digs into the implications.

But it’s a rich book, one that gave me insight not just into my society but into myself. I used to be an atheist, today am a Christian, and am certain the evangelical church that I currently attend won’t be my final spiritual landing spot. An Eastern Orthodox depiction of Jesus hangs in my home, I’ve been deepening my understanding of scripture by learning about the Jewish Sabbath, and I don’t think weed or psychedelics should be verboten for believers. In other words, I’m remixed. But that syncretic faith has been a gateway drug to something more like traditional religion, drawing me to a place of sturdier Christian belief and more durable community. And I don’t think I’m the only one who can say that.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2FxF81O

via IFTTT

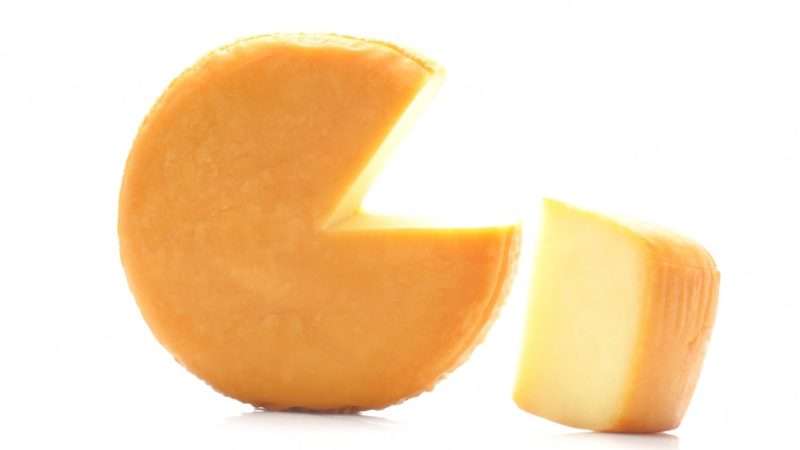

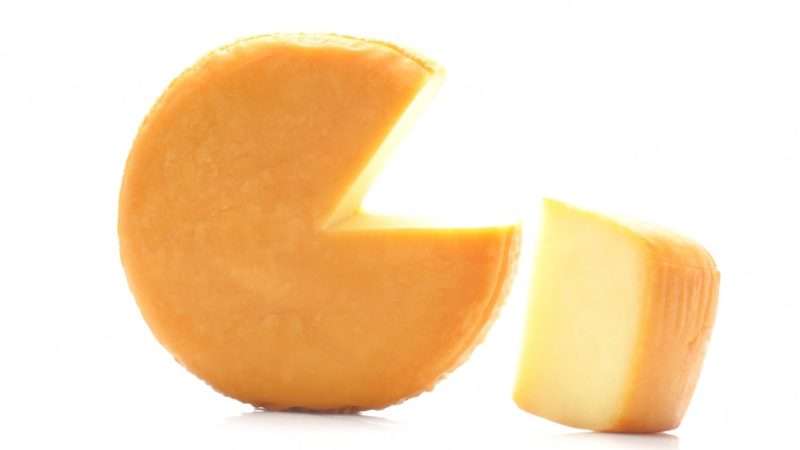

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. Department of Agriculture granted California a waiver to the Commodity Supplemental Food Program, which provides boxes of food to low-income households, allowing the state to remove cheese from the boxes. Cheese is the only food in the box that needs to be refrigerated, and removing it allows the boxes to be delivered to seniors who have been advised to shelter in place rather than forcing them to come in to pick up the boxes. But that waiver has expired, and the USDA won’t renew it, saying cheese is a vital part of the boxes. It’s also a vital part of federal efforts to bolster the price of cheese by buying it from farmers and giving it away. The state reports that the number of seniors getting the boxes has dropped 30 percent since the waiver expired.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2ZGvDEx

via IFTTT

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. Department of Agriculture granted California a waiver to the Commodity Supplemental Food Program, which provides boxes of food to low-income households, allowing the state to remove cheese from the boxes. Cheese is the only food in the box that needs to be refrigerated, and removing it allows the boxes to be delivered to seniors who have been advised to shelter in place rather than forcing them to come in to pick up the boxes. But that waiver has expired, and the USDA won’t renew it, saying cheese is a vital part of the boxes. It’s also a vital part of federal efforts to bolster the price of cheese by buying it from farmers and giving it away. The state reports that the number of seniors getting the boxes has dropped 30 percent since the waiver expired.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2ZGvDEx

via IFTTT

Politicians shut down businesses because of COVID-19.

But the rules don’t apply to everyone.

In San Francisco, gyms were forced to close, but (SET ITAL)government(END ITAL) gyms stayed open.

In my new video, we see a Dallas woman being jailed for keeping her salon open and a New Jersey man getting arrested after working out indoors.

Ordinary people who break the rules get punished.

But not House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Politicians are special.

Now, politicians have allowed more businesses to open. Dallas relaxed its rules for most businesses a few months ago.

But not for Dale Davenport’s car wash. Dallas won’t allow Dale to reopen because, shortly before the epidemic, they decreed his car wash a “hub for drug sales and crime.”

His car wash is indeed in the middle of a high-crime neighborhood, and many cities have laws that let them close a business if the owners conceal crime.

But Davenport didn’t do that. When he saw crime, he called 911. Dallas politicians then used his 911 calls against him, saying his frantic phone calls were evidence his business was a “public nuisance.”

“This is absolutely crazy,” complains Davenport.

Still, Davenport “bent over backwards” to do almost everything the politicians asked him to do.

“They said (to reduce crime), build a six-foot fence. I built an eight-foot fence,” he tells me. “Then they said, put up signs. I already had signs up, so I put up more signs. Then they told me to put up lights. I already had lights up, so I put up more lights.”

That still wasn’t enough. The city came in and closed his business, anyway. “They murdered my business,” says Davenport.

Closing it didn’t reduce crime. Crime in the neighborhood stayed about the same.

But the community lost a center. For 20 years, people drove to Dale’s car wash, and then visited other local businesses while their cars were washed.

“The businesses next to my car wash, their business is down 40-50%,” says Davenport.

Why did politicians go after just one business that was well lit and where the owner did most of what the politicians requested?

Davenport suspects the politicians shut him down because he won’t give money to their friends. The city told him to hire armed guards, but when he hired them, he says he was told, “You’ve hired the wrong guard company.” He hadn’t hired a guard company owned by a city councilman.

Could it be that corrupt Dallas politicians want the money for themselves?

“This is extortion,” says Davenport.

We contacted all 14 city council members. Not one agreed to an interview.

Dallas has a rich history of political corruption. The guard company Davenport says the city wanted him to hire was owned by former councilman James Fantroy. In 2008, Fantroy went to prison for stealing $20,000 from a college.

Former Dallas city council members Dwaine Caraway, Paul Fielding and Don Hill were all jailed after being convicted of bribery or extortion.

Instead of paying car wash employees, Davenport now spends his money on lawyers, hoping to fight city hall. “This is wrong,” says Davenport. “This is tyranny.”

It’s bad enough when politicians kill businesses with COVID-19 shutdowns. It’s worse if they kill a business because the owner won’t give money to their friends.

COPYRIGHT 2020 BY JFS PRODUCTIONS INC.

DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/32vTvMW

via IFTTT

The New York Times describes Sweden’s approach to COVID-19, which has been notably less restrictive than the policies adopted by other European countries and the United States, as “disastrous” and “calamitous.” By contrast, Scott Atlas, the physician and Hoover Institution fellow who is advising President Donald Trump on the epidemic, thinks Sweden’s policy is “relatively rational” and “has been inappropriately criticized.”

The sharp disagreement about Sweden is part of the wider debate about the cost-effectiveness of broad lockdowns as a strategy for dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. While it is premature to reach firm conclusions, the evidence so far suggests that Sweden is faring better than the United States, where governors tried to contain the virus by imposing sweeping social and economic restrictions.

Despite some early blunders (most conspicuously, the failure to adequately protect nursing home residents), Sweden generally has tried to protect people who are at highest risk of dying from COVID-19 while giving the rest of the population considerably more freedom than was allowed by the lockdowns that all but a few governors in the United States imposed last spring. That does not mean Swedes carried on as usual, since the government imposed some restrictions (including a ban on large public gatherings) and issued recommendations aimed at reducing virus transmission.

The consequences of that policy look bad if you compare Sweden to Denmark, Finland, and Norway, neighboring countries that have seen far fewer COVID-19 deaths per capita. Yet Sweden has a lower death rate than several European countries that imposed lockdowns, including Belgium, Italy, Spain, and the U.K.

The comparison between Sweden and the United States is especially striking. The per capita fatality rate in the U.S. recently surpassed Sweden’s rate, and the gap is growing, since the cumulative death toll is rising much faster in the United States.

The seven-day average of daily deaths peaked around the same time last spring in both countries. Adjusted for population, the peak was higher in Sweden.

Since then, however, that average has fallen more precipitously in Sweden—by 99 percent since April 16, compared to 65 percent in the United States since April 21. The seven-day average of newly confirmed cases also has dropped sharply in Sweden, by nearly 80 percent since late June.

In the United States during the same period, daily new cases initially rose, an ascent that started a month and a half after states began lifting their lockdowns. The seven-day average peaked in late July and has since fallen by 46 percent.

Achieving herd immunity, which protects people in high-risk groups by making it less likely that they will encounter carriers, was never an official goal of Sweden’s policy. But recent trends are consistent with the hypothesis that Sweden has achieved some measure of herd immunity through a combination of exposure to the COVID-19 virus, T-cell response fostered by prior exposure to other coronaviruses, and greater natural resistance among the remaining uninfected population.

In the United States, meanwhile, lockdowns, despite the huge costs they entailed, have not had any obvious payoff in terms of fewer COVID-19 deaths, although they may have changed the timing of those deaths. Perhaps the outcome would have been different if lockdowns had been imposed earlier or if they had been lifted later and more cautiously.

But perhaps not. In a National Bureau of Economic Research paper published last month, UCLA economist Andrew Atkeson and two other researchers, after looking at COVID-19 trends in 23 countries and 25 U.S. states that had seen more than 1,000 deaths from the disease by late July, found little evidence that variations in policy explain the course of the epidemic in different places.

Atkeson and his co-authors conclude that the role of legal restrictions “is likely overstated,” saying their findings “raise doubt about the importance” of lockdowns in controlling the epidemic. It would not be the first time that people have exaggerated the potency of government action while ignoring everything else.

© Copyright 2020 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/35ARAZs

via IFTTT

Politicians shut down businesses because of COVID-19.

But the rules don’t apply to everyone.

In San Francisco, gyms were forced to close, but (SET ITAL)government(END ITAL) gyms stayed open.

In my new video, we see a Dallas woman being jailed for keeping her salon open and a New Jersey man getting arrested after working out indoors.

Ordinary people who break the rules get punished.

But not House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Politicians are special.

Now, politicians have allowed more businesses to open. Dallas relaxed its rules for most businesses a few months ago.

But not for Dale Davenport’s car wash. Dallas won’t allow Dale to reopen because, shortly before the epidemic, they decreed his car wash a “hub for drug sales and crime.”

His car wash is indeed in the middle of a high-crime neighborhood, and many cities have laws that let them close a business if the owners conceal crime.

But Davenport didn’t do that. When he saw crime, he called 911. Dallas politicians then used his 911 calls against him, saying his frantic phone calls were evidence his business was a “public nuisance.”

“This is absolutely crazy,” complains Davenport.

Still, Davenport “bent over backwards” to do almost everything the politicians asked him to do.

“They said (to reduce crime), build a six-foot fence. I built an eight-foot fence,” he tells me. “Then they said, put up signs. I already had signs up, so I put up more signs. Then they told me to put up lights. I already had lights up, so I put up more lights.”

That still wasn’t enough. The city came in and closed his business, anyway. “They murdered my business,” says Davenport.

Closing it didn’t reduce crime. Crime in the neighborhood stayed about the same.

But the community lost a center. For 20 years, people drove to Dale’s car wash, and then visited other local businesses while their cars were washed.

“The businesses next to my car wash, their business is down 40-50%,” says Davenport.

Why did politicians go after just one business that was well lit and where the owner did most of what the politicians requested?

Davenport suspects the politicians shut him down because he won’t give money to their friends. The city told him to hire armed guards, but when he hired them, he says he was told, “You’ve hired the wrong guard company.” He hadn’t hired a guard company owned by a city councilman.

Could it be that corrupt Dallas politicians want the money for themselves?

“This is extortion,” says Davenport.

We contacted all 14 city council members. Not one agreed to an interview.

Dallas has a rich history of political corruption. The guard company Davenport says the city wanted him to hire was owned by former councilman James Fantroy. In 2008, Fantroy went to prison for stealing $20,000 from a college.

Former Dallas city council members Dwaine Caraway, Paul Fielding and Don Hill were all jailed after being convicted of bribery or extortion.

Instead of paying car wash employees, Davenport now spends his money on lawyers, hoping to fight city hall. “This is wrong,” says Davenport. “This is tyranny.”

It’s bad enough when politicians kill businesses with COVID-19 shutdowns. It’s worse if they kill a business because the owner won’t give money to their friends.

COPYRIGHT 2020 BY JFS PRODUCTIONS INC.

DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/32vTvMW

via IFTTT

The New York Times describes Sweden’s approach to COVID-19, which has been notably less restrictive than the policies adopted by other European countries and the United States, as “disastrous” and “calamitous.” By contrast, Scott Atlas, the physician and Hoover Institution fellow who is advising President Donald Trump on the epidemic, thinks Sweden’s policy is “relatively rational” and “has been inappropriately criticized.”

The sharp disagreement about Sweden is part of the wider debate about the cost-effectiveness of broad lockdowns as a strategy for dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. While it is premature to reach firm conclusions, the evidence so far suggests that Sweden is faring better than the United States, where governors tried to contain the virus by imposing sweeping social and economic restrictions.

Despite some early blunders (most conspicuously, the failure to adequately protect nursing home residents), Sweden generally has tried to protect people who are at highest risk of dying from COVID-19 while giving the rest of the population considerably more freedom than was allowed by the lockdowns that all but a few governors in the United States imposed last spring. That does not mean Swedes carried on as usual, since the government imposed some restrictions (including a ban on large public gatherings) and issued recommendations aimed at reducing virus transmission.

The consequences of that policy look bad if you compare Sweden to Denmark, Finland, and Norway, neighboring countries that have seen far fewer COVID-19 deaths per capita. Yet Sweden has a lower death rate than several European countries that imposed lockdowns, including Belgium, Italy, Spain, and the U.K.

The comparison between Sweden and the United States is especially striking. The per capita fatality rate in the U.S. recently surpassed Sweden’s rate, and the gap is growing, since the cumulative death toll is rising much faster in the United States.

The seven-day average of daily deaths peaked around the same time last spring in both countries. Adjusted for population, the peak was higher in Sweden.

Since then, however, that average has fallen more precipitously in Sweden—by 99 percent since April 16, compared to 65 percent in the United States since April 21. The seven-day average of newly confirmed cases also has dropped sharply in Sweden, by nearly 80 percent since late June.

In the United States during the same period, daily new cases initially rose, an ascent that started a month and a half after states began lifting their lockdowns. The seven-day average peaked in late July and has since fallen by 46 percent.

Achieving herd immunity, which protects people in high-risk groups by making it less likely that they will encounter carriers, was never an official goal of Sweden’s policy. But recent trends are consistent with the hypothesis that Sweden has achieved some measure of herd immunity through a combination of exposure to the COVID-19 virus, T-cell response fostered by prior exposure to other coronaviruses, and greater natural resistance among the remaining uninfected population.

In the United States, meanwhile, lockdowns, despite the huge costs they entailed, have not had any obvious payoff in terms of fewer COVID-19 deaths, although they may have changed the timing of those deaths. Perhaps the outcome would have been different if lockdowns had been imposed earlier or if they had been lifted later and more cautiously.

But perhaps not. In a National Bureau of Economic Research paper published last month, UCLA economist Andrew Atkeson and two other researchers, after looking at COVID-19 trends in 23 countries and 25 U.S. states that had seen more than 1,000 deaths from the disease by late July, found little evidence that variations in policy explain the course of the epidemic in different places.

Atkeson and his co-authors conclude that the role of legal restrictions “is likely overstated,” saying their findings “raise doubt about the importance” of lockdowns in controlling the epidemic. It would not be the first time that people have exaggerated the potency of government action while ignoring everything else.

© Copyright 2020 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/35ARAZs

via IFTTT

In June, in Davenport v. MacLaren, a divided panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit overturned Ervine Lee Davenport’s first-degree murder conviction because “he was visibly shackled at the waist, wrist, and ankles during trial.” Judge Stranch wrote for the court, joined by Chief Judge Cole. Judge Readler dissented.

Today, by a vote of 8-7, the full Sixth Circuit denied the state of Michigan’s petition for rehearing en banc, even though nine of the sixteen judges believe the original panel decision was wrong. Two of the judges on the court, Judges Sutton and Kethledge, concluded that the panel decision was wrong, but not en banc worthy (something these same judges have concluded before).

Judge Stranch wrote an opinion concurring in the denial of rehearing en banc, on the grounds that the panel decision was correct. Judge Stranch’s opinion was joined by Chief Judge Cole and Judges Moore, Clay, White, and Donald.

Judge Thapar dissented from the denial of rehearing en banc, joined by Judges Bush, Larsen, Nalbandian, Readler, and Murphy. Judge Thapar’s opinion begins:

Thirteen years ago, on a cold night in January, Earl Davenport killed Annette White. He closed his hand around her neck and held it there as she struggled against him. Minutes later, she was dead.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of Davenport’s guilt, a panel majority voted to vacate his conviction. It did so without even applying AEDPA deference to the state court’s harmless-error determination.

This tragic case thus presents a fundamental question of habeas jurisprudence: Must a state court’s harmless-error determination receive AEDPA deference under 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1)? The plain text of the statute says that the answer is yes. But the panel majority held that the answer is no. According to the panel opinion, federal judges can simply ignore AEDPA’s guardrails whenever they find that a petitioner has suffered actual prejudice under Brecht v. Abrahamson, 507 U.S. 619 (1993). This holding casts aside AEDPA and misinterprets Supreme Court precedent. That matters because AEDPA’s procedural rules have bite that Brecht lacks. The holding also deepens an existing circuit split. And what’s more, the panel opinion defies Brecht itself, granting habeas relief based on mere speculation and a thin stack of academic articles, some of which postdate the state court’s decision.

Given these errors and their importance, this case merited the attention of the en banc court. I respectfully dissent.

Judge Sutton, joined by Judge Kethledge, agreed that the panel misapplied the law, but nonetheless concurred in the denial of the petition for rehearing en banc. From Judge Sutton’s opinion:

This en banc petition implicates a nagging tension between deciding cases correctly and delegating to panels of three the authority to decide cases on behalf of the full court. . . .

The[] problems with the panel’s decision and its debate over Chapman/Brecht seem to be recurring ones in our circuit and outside of it, suggesting that there is room for clarification by the Supreme Court when it comes to federal court review of state court harmless-error decisions under AEDPA—and the process obligations of lower courts in applying the statute. Just read the eighteen combined pages devoted to the standard of review by this one panel for evidence. It’s been five years since the Court’s most recent contribution to the area and of course many decades since Chapman and Brecht. I suspect every federal judge in the country would welcome guidance in the area. . . .

The problem at hand turns mainly on what to make of language in Supreme Court decisions, . . . Countless inefficiencies arise when a full intermediate court debates the meaning of vexing language from the Supreme Court, the most obvious being this: Not only are we fallible, we are not final either.

Judge Griffin responded to Judge Sutton in a separate dissent from denial of rehearing en banc, emphasizing the standards for en banc review in the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. From his opinion:

By the vote of 8–7, our en banc court has denied respondent’s petition for rehearing en banc. This is most unfortunate for our circuit because the 2–1 panel opinion conflicts with a previous decision of our court and is clearly wrong on a habeas-corpus issue of exceptional importance. While some of my colleagues agree, they nevertheless have opposed the petition in the hope that the Supreme Court will reverse us yet again to clean up our intra-circuit mess. This denial of rehearing en banc is reminiscent of CNH Industrial N.V. v. Reese, 138 S. Ct. 761

(2018), wherein we were reversed unanimously by the Supreme Court in a per curiam opinion and admonished that “the en banc Sixth Circuit has been unwilling (or unable) to reconcile its precedents.” Id. at n.2.The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure provide an important and necessary remedy for courts of appeals to correct their conflicts and errors of exceptional importance. . . .

Because our litigants, attorneys, and judges need guidance from our en banc court on these issues of exceptional importance, I would grant respondent’s petition for rehearing en banc.

For what it’s worth, I have lots of sympathy for Judge Sutton’s general point that not every wrong panel decision merits en banc review, and that some questions need to be resolved by the Supreme Court. That said, this case seems to satisfy the traditional requirements for en banc review, particularly given the need for clarity and consistency, and the apparent inconsistencies within the Sixth Circuit’s own caselaw.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3iyx7YY

via IFTTT