It’s not just Silicon Valley which is suddenly scrambling to monetize its VC investments after years of harvesting private company gains in hopes of top-ticking the market ahead of a broader crash: so is China’s tech scene.

After years of buoyant excess reminiscent of the craziest west coast startups, thousands of Chinese tech employees are suddenly finding themselves without a job, while those who remain find that perks like free snacks and travel, gym memberships, new year bonuses, and yes, even fruit bowls, are now gone as the new mood across China’s tech heartland, from Shenzhen to Hangzhou, is one of painful austerity.

The math is simple: as the FT reports, with the Chinese economy slowing and foreign capital flows shrinking, start-ups are cutting costs. “For an internet start-up you need people, capital and customers. And they are going to see erosion in every one of these categories,” says one disappointed Chinese tech investor.

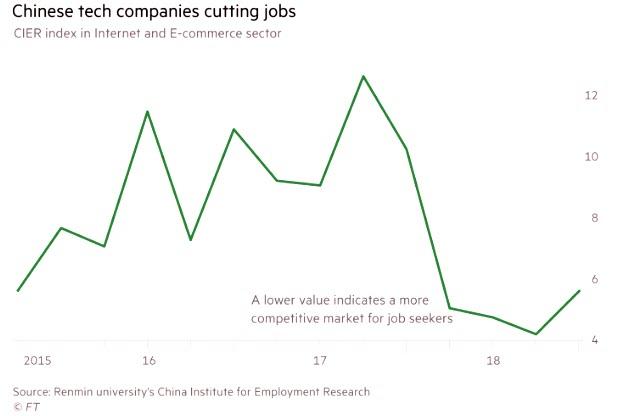

Whether or not it is tied to Trump’s trade war with Beijing is debatable, but China’s pain clearly started in the second half of 2018 when capital began drying up resulting in tumbling valuations of formerly flying tech companies. Not helping are local consumers who have become more thrifty, as seen in China’s plunging car sales, resulting in advertisers rethinking budgets. But it’s the workers who are bearing the brunt of cutbacks.

Tao Jiali, a recent casualty of what gaming group NetEase euphemistically dubbed “structural optimisation”, sums up the mood. “Everyone is jittery,” she said. The latest blow came on Friday, with reports that Dianrong, a peer-to-peer lender, would shed 2,000 staff.

To get a sense of the worker unease and in some cases, desperation, Zhaoping.com, an online recruitment site that boasts 180m registered users, said that record numbers of resumes are doing the rounds. “Changes in the market environment have brought the development of the internet industry back to a rational state,” said Li Qiang, executive vice-president. He cited two other issues: after years of growth, internet user numbers have reached a plateau, escalating competition and hurting margins. And regulatory clampdowns are hurting everything from gaming to ecommerce to social media.

To be sure, China’s economic slowdown is also hitting the broader economy, and as we reported last night, for the first time ever, China’s working population shrank in 2018.

But nowhere is the pain more acute than in the highest paying tech jobs; for proof look no further than China’s private valuation titan Didi, which despite successfully chasing Uber out of China in 2016, has more recently faced fierce government pressure after two women were murdered using its carpooling service, and is now laying off 2,000 employees, or 15% of the workforce. For the remaining employees, year-end bonuses were cut in half in December and perks such as free snacks and subsidised gym membership have gone.

“We recently made adjustments to these [workplace] benefits, however we have no plans to make any major cuts,” said a spokesman for the company.

Another formerly high-flying Chinese tech giant is JD.com, whose recent problems have been compounded by internal issues — its founder and chief executive Richard Liu was arrested in the US last year on suspicion of rape, although no charges were brought. Even so, the company is suddenly laser focused on maximizing profits and is trumming its ranks of middle management, planning to cut about 10% of those at vice-president level and above.

Yet while both companies vow to hire enough workers to offset those who were laid off, a more ominous shift in the industry is taking place: advertising budgets – the bread and butter of most tech names not only in China but around the globe – will grow just 17% this year, just a bit more than half the rate of the past two years, according to Jefferies estimates.

Even this, the FT writes, may be optimistic. Industry players point to “a big step down” in actual ad budgets compared with expectations that were set a the start of last year, when advertisers’ revenues were still surging ahead. That, said analysts, will hurt the likes of fast-growing ByteDance, which scrimped on the money it stuffed in workers’ hongbao, the red money packets traditionally given out at Chinese new year.

Then, in typical Chinese fashion, CEO Zhang Yiming sent out a memo urging staff to temper their disappointment, blaming the smaller bonuses on the “external environment, industry competition and our own errors and deficiencies in management, decision making and implementation”.

While the group, which includes the massively popular short video app Douyin, has grown to a value of $75BN in seven years and started hiring across the world, its best years appear to be behind it: the group’s woes suggest growing pains are starting to bite. Like its peers, it has chafed with regulators over content, both at home, and in the US — and its reliance on ads make it vulnerable to the weaker economy, the FT notes.

The punchline: as periods of austerity go, this one is unlikely to be short.

“It’s just the beginning of the lay-offs we are going to see for the next two or three years,” one tech investor told the FT, while Wang Xing, whose food delivery app Meituan Dianping has so far resisted talk of job cuts, took to social media with an even more blatant example of gallows humor: “I heard a joke that 2019 may be the worst in the past 10 years, but it may be the best in the next 10 years.”

One thing is clear: China’s domestic workers know their economy best, and it certainly does not appear that the world’s second biggest economy is set for a sharp rebound. In fact, if Trump were to delay rushing a trade deal with Beijing, it certainly appears that any incremental leverage and negotiating advantage would be solely in his favor as Beijing scrambles to keep its economy from disintegrating any more.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2C4WOND Tyler Durden