U.S. farmers are defaulting and missing payments at alarming rates, forcing regional banks to restructure and refinance existing loans, according to Bloomberg. Regional banks, although still considered “healthy” for the most part, are requiring farmers to post increased collateral to “boost their defenses” against additional looming losses and default risks, further depressing US farm production while putting even more loans in danger of default.

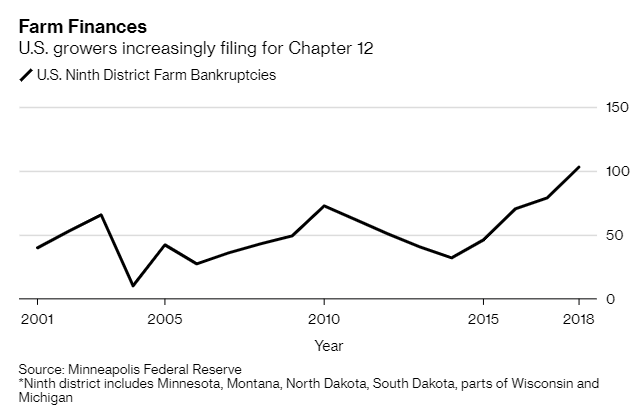

According to a report by First Midwest Bank, past-due agricultural loans have soared 287% in 2018 vs the prior year. Additionally, cases handled by the Iowa Mediation Service involving farmers unable to make payments. jumped 20%. In six Midwest states, farmer bankruptcies rose 30% to 103 in 2018. This has caused banks like Farmers National Bank in Prophetstown, Illinois to restructure more loans in order to keep growers solvent while at the same time limiting their own risk.

Don Vogel, the bank’s president and chief executive officer said: “when you’re a rural community bank, if you’re not involved in agriculture, you probably don’t have a future.” Farmer loans make up 79% of his bank’s portfolio and include “probably three generations” of farmers. He continued: “It is a long rough patch and it’s probably going to last longer. There’s not one little thing that you can neglect during these times.”

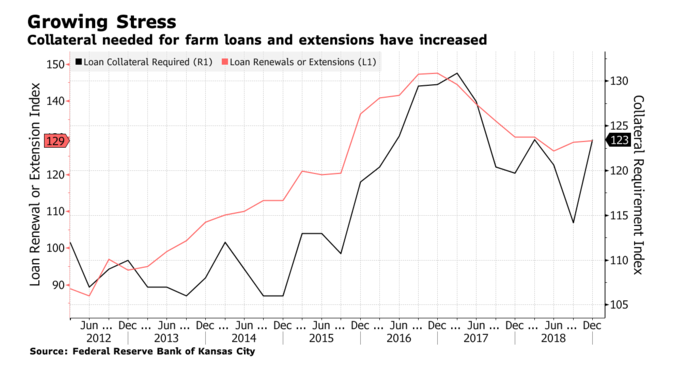

According to a survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, conditions that prompted lenders to ask for more collateral were up 2.5% in Q4 2018. Meanwhile, the average interest rate on farm operating loans moved up to 6.07%, the highest level since Q2 2010.

As discussed recently, Farmers’ income has continued to slide and is down 11% since 2010 while, over the same period, expenses have risen 31% as a result of crop prices falling and the continued trade war with China. Floods in the midwest have also acted as headwinds for some growers, leaving others with delays and useless flooded supplies.

Steve Myers, a senior vice president at Busey Bank in LeRoy, Illinois, said he’s seeing more farmland sold, though the selling isn’t yet “rampant”. He commented: “…it signals a warning sign of sorts. The warning shots are valid. The warning shots are here.”

Kiley Fleming, executive director of the Iowa Mediation Service, said that state laws provide borrowers the option to mediate with creditors before foreclosures. Often times, this can lead to selling machinery or restructuring loans, instead of foreclosure.

While she says her days have gotten longer, she also says that her team has been able to find resolutions 80% of the time.

The problem for the banks is that many farmers aren’t in a position to refinance, so they instead wind up selling assets. This has led to North American farm tractor inventories jumping 8% over the past year, to record highs, in March. Fleming has also tried to get Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican, to push new legislation to help farmers forced into bankruptcy.

Chris Kalkowski, vice president of agribusiness banking at First National Bank of Omaha said:

“Banks are working with their customers, trying to figure out how to keep them going. If you need liquidity, the advice is being given, you’re going to have to create it by doing something. And a lot of the time, that turns out to be selling some assets.”

Senator Chuck Grassley is already taking “steps to try and help”. Grassley, along with a bipartisan group of senators, recently introduced a bill that would help farmers reorganize by raising the Chapter 12 operating debt cap to $10 million from about $4.2 million. Grassley said: “Even if the trade war ends, with this oversupply of corn and soybeans and wheat, we’re still going to have low prices.”

Meanwhile, as discussed last week, personal income for farmers is down 25% this year, the sharpest decline since the first three months of 2016, but the banks are holding their own – for now. The future looks bleak, however. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City predicted last month that farmland prices could keep falling, a divergence from what normally happens during a downturn, when farm prices usually hold their value and become attractive collateral.

Becky King, director of the agricultural lending group at First Midwest concluded: “This would be, in many cases, the fourth or the fifth year where these profitability issues are occurring, depending on the farm. The bank isn’t seeing more foreclosures, but it is seeing more stress.”

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2Vj6TBW Tyler Durden