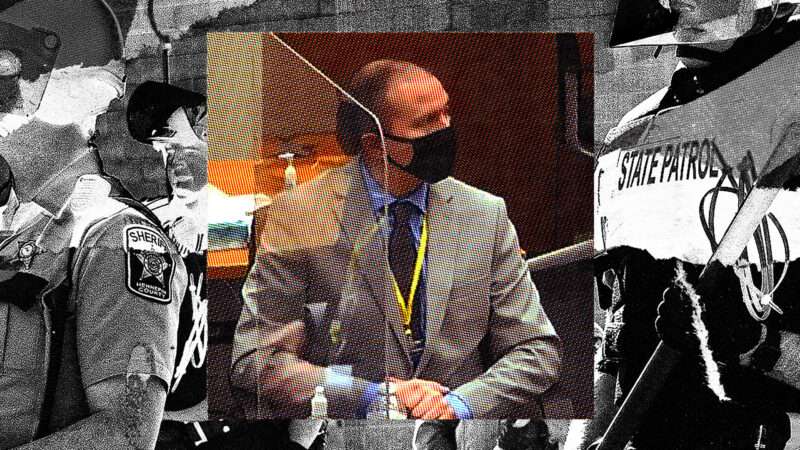

It’s 10:45 a.m. and the murder trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, taking place inside the Hennepin Courthouse in downtown Minneapolis, has entered day two. Outside the courthouse, a handful of people have gathered near a cyclone fence festooned with paper hearts and lined with paintings of Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. “All cops are bastards!” chant the assembled. “Indict! Convict! Send that killer cop to jail! The whole damn system is guilty as hell!”

One person not chanting at the moment is Kaia Hirt, who is busy adjusting the heavy chain that she has lashed across her chest and locked to the cyclone fence. A tenth grade English teacher in Champlin, 25 miles north of Minneapolis, Hirt tells me that while she had previously attended “multiple protests throughout the suburbs and in the Twin Cities areas,” the death of George Floyd catalyzed for her the urgent need to fight racist policies and actions.

With the temperature at around 35 degrees and an icy wind making one wish for mittens, Hirt, of Korean extraction and wearing a Black Lives Matter face mask, allows herself to be covered in a blanket as she tells me where she was when George Floyd was killed and why she is here today. Her comments have been edited for length and clarity.

“I am a local activist and organizer and I decided to chain myself to this fence to draw attention to the fact that there are 450 people who were killed by the police in Minnesota since 1984. Their families are still seeking justice for those police homicides. I’ve always protested and I’ve always considered my job as an educator to be an anti-racist and to include [anti-racist] narratives in my curriculum. I always hoped that teaching would help me make a difference in people’s lives and in the world, but after George Floyd, I really felt I needed to do more.”

Do you remember where you were when you learned George Floyd had died in police custody?

“I think I was at home and I was on social media when I first saw it, and obviously, like all of us, it was devastating. I was speechless. I cried. And you know, when you teach young black men, and you see the way they’re treated, even in schools, you know that they could be next. The research has been done that people tend to see black males as much older than they are. And treat them as such, even when they’re just boys. Look at Tamir Rice. And so my fear for my students is part of what drives me to be involved. I live in a suburb that is fairly privileged and affluent, Minnetonka, and I’m frustrated with the lack of involvement that I see in the community and sort of an apathy towards things that are happening. And so I began by hosting events out there.”

You were in Minnetonka after Floyd’s death. Did you see much violence in your area?

“Not personally, no. I mean, I definitely protested in the city during that period of time, and I actually protested on a couple of days that later became quite tumultuous. I have friends who were very fearful, who lived in the neighborhood [where Floyd died] at the time, and the constant helicopters; sleeping in the basement instead of the bedroom; sleeping with weapons that they could find around the house, like a hammer or a golf club.

I believe they were afraid of the unrest that was occurring, and also very afraid of police. My friends were BIPOC [black, indigenous, and people of color]. I was told there were citizen patrols trying to protect their blocks from vandalism or looters or whatever, and I said to a friend, ‘Are you gonna go out?’ And he said, ‘You know, it’s a little different when you’re not white, to go out and try to protect your neighborhood and carry weapons. I could easily be mistaken in some way and be harmed myself.'”

The reaction to Floyd’s death has been enormous and profound, hundreds of millions of people around the world responding or being affected by what happened to one person in Minneapolis. What would you say to any naysayers who question this response, who say, there’s something going on that is out of proportion to the killing itself?

“I would say those naysayers are absolutely ridiculous and do not understand white supremacist history. I would say those naysayers have not studied slavery. African people were abducted from Africa, taken away from their families on slave ships, brought to this country to labor for free, tortured, humiliated, dehumanized, raped, and killed, followed by a century of lynching; 8,000 people in this country were lynched without trial, without accusation, sometimes with the police being involved. Segregation, which you have from the 1860s to 1960s, essentially legalized racism, where people of color were compared with dogs; the restaurant signs would say, ‘No Dogs, No Mexicans, No Negroes.’ There were segregated water fountains, segregated schools, and it was all hidden under the guise of separate but equal, which we all know is a lie because those things were not equal.

And then we take a look at the disparities today, particularly here in Minnesota. What you are talking about is disparities in health care, disparities in education, disparities in housing, disparities in employment. How can you say, how can these naysayers—or dare I say white supremacists—say that there is an overreaction to a cop kneeling on a man’s neck, for nine minutes, killing him, over a $20 forged bill? I’m not even gonna say the words that come to mind because you’re recording me, but I’ll tell you what, that is unacceptable. Those people should be ashamed.”

What do you expect to happen on the ground now? I was told there were thousands of activists from other cities descending on Minneapolis for the trial.

[Hirt laughs.] “There’s five of us now.”

Five, exactly. What are you expecting to happen?

“Listen, the people of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, the activists, we’re tired. We are very tired because we have been fighting for justice not just for George Floyd, but for these 450 people who have lost their lives to police homicide, and you know what? If we’re angry, we have every right to be angry. We are a peaceful group. We are about peace, we are about safety, and we are about love. We don’t burn our own community down, but I’ll tell you what, Martin Luther King Jr. said that riots are the language of the unheard. People of color have been asked to wait. ‘A right delayed is a right denied,’ OK? And so what we’re talking about is the language of the unheard. The idea that, oh, the liberal white moderate says, ‘Follow proper channels. Wait, this isn’t the right time. Can you do it like this and not like that? Can you please do it in a way that’s pleasing to us; that isn’t scary to us?’

We follow proper channels. We try to use democracy. Now we run into obstacles to voting, right? Voter suppression. We try to do it through…I can’t even, I’m so enraged right now. We have followed proper channels and they’re not working. Nothing is changing. Black people are being killed for holding a cellphone while mass shooters, white mass shooters, are apprehended without a hair hurt on their head. There is a disparity and a double standard there that is unacceptable, and anyone who is paying attention can see it.”

If the trial has a dissatisfying outcome, what happens in the city?

“We are peaceful activists. You need to understand American history, white supremacist history, to understand the suffering and oppression of black people and other people of color, Native indigenous people, okay?”

I have a Native daughter.

“But you’re still white.”

True.

“If there is rioting, that would be completely understandable and that is what Martin Luther King Jr. tells us. He says that we have been unheard; we have been told to wait; we have been told that we’re not resisting in the right way. What is the right way? We kneel during the national anthem. Well, that’s not okay. What is okay? What is peaceful?”

How long do you plan to stay chained here?

“As long as I fucking feel like it. These locks are peaceful. This is a peaceful demonstration. It does not destroy the property. It is not violent. It isn’t even loud. Every lock has the name of a person who was killed by the police [written on it]. A person who was killed by the police, along with their story. These aren’t just names. There are stories behind how they were killed.

I’m not saying there will be, but I’m saying, if there are riots [after the trial], you need to understand American history. You need to understand hundreds of years of flat-out oppression and efforts to change everything in a peaceful way. It doesn’t justify anything, but it explains it. And I would not judge one single person if this city burns.”

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3dqAVKg

via IFTTT