Short Interest Ratio Vs Borrow Cost, Or How To Avoid Short Squeezes

By Russell Clark of the Capital Flows and Asset Markets substack

I was having lunch with an old fund manager friend, and we were talking about my recent post – the three profit centers of short selling. I suddenly realized we were getting short interest ratio and borrow cost of a short mixed up. If veteran short sellers could get this concept confused, then anyone could. I thought I would do a quick presentation on the difference between the two and why it is important to distinguish between the two. In my view, borrow cost is a much better metric to look at, as it will be more likely to help you avoid career ending short squeezes.

Short squeezes are part and parcel of life in markets. The problem for short sellers is that as the losses on short selling are unlimited, markets know that if you can push a price high enough, the short seller MUST buy back the position. So short sellers tend to look at various metrics to work out how crowded a position is. One metric is a short interest ratio. Another is cost of borrow. In my experience, cost of borrow is a much better indicator of potential for a short squeeze.

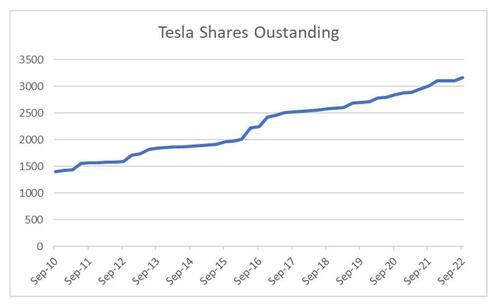

Let’s talk about the short interest ratio first. This ratio is the number of shares out short divided by the number of shares outstanding, is actually widely reported and can be downloaded directly from Bloomberg is you wish. Let us look at one of the worst shorts in history – Tesla. From the moment Tesla was listed it had a very high short interest ratio. For the first few years of its life its short interest was regularly in the 30% range, before collapsing down to much lower levels.

But as can be seen above, Tesla’s short interest ratio fell but short interest never fell. The reason for this is because Tesla has constantly issued shares to fund its capital expenditures.

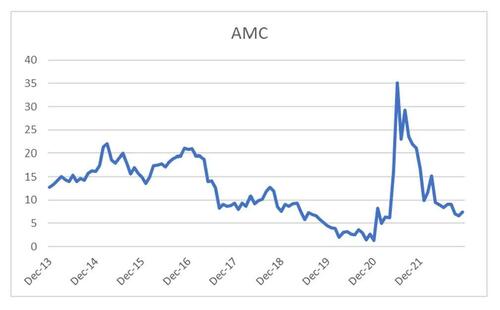

Tesla is a good example of short interest ratio falling not really indicating the stock is safe from a short squeeze. In 2013, when Tesla did a large capital raising, its short interest ratio fell, but actual total short interest remained high. The reason it remained high was that analysts could still see that there would be future capital raisings, which was correct, but unfortunately for short sellers the stock went massively against them. High levels of absolute short interest always run the risk of a squeeze. Another short squeeze where short interest ratio failed to indicate a short squeeze risk was AMC.

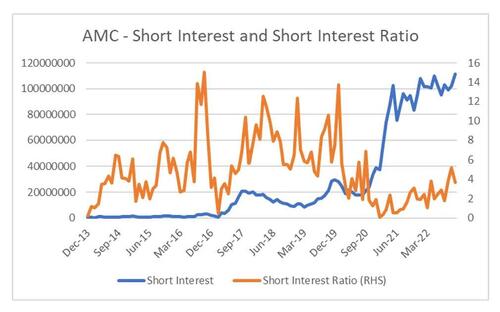

For short sellers in 2020 looking at both the short interest ratio, it was well below levels seen in 2015, but total short interest was near highs, but neither gave a particularly strong warning that AMC was about to have a career ending short squeeze. In fact, despite a relatively high short interest ratio, AMC had been a “wonder short” form mid 2018 to early 2020, before spiking to new all-time highs during Covid.

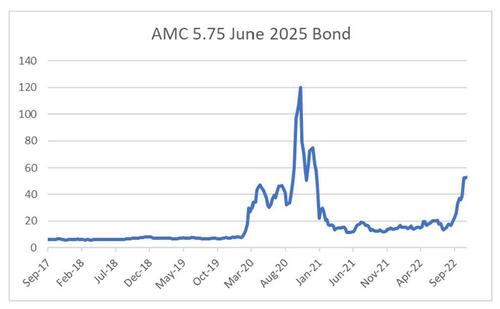

For this reason, I have tended to focus on cost of borrow to limit short squeeze risk. To put it simply stocks where the borrow cost is less than two percent. Unfortunately, data on the borrow cost is not freely available and can vary according to who is lending the stock out, and who wants to borrow it. But that being said, borrow cost for short selling a stock is very highly correlated with corporate borrowing costs. If we look at the CDS for Tesla, it was at 700 in mid 2019, before collapsing down to a low of 100 in 2021. That is stock borrow would have been expensive in 2019, before falling through 2021.

With AMC we have a traded corporate bond we can look at rather than CDS. As corporate bonds yield rise, cost of borrow also rises. If we look at the 5.75 June 2025 AMC bond, it was relatively well behaved until Covid hit, and the bonds were priced for default very rapidly, something that is now occurring again.

With AMC bonds selling off again, cost of borrow to short the stock is 33% roughly. That means I need to pay to a long owner willing to lend me the stock 33% annually. The way I interpret very high borrow costs is that the stock is a popular short, which we can see from the very high levels of absolute short interest, but also a very unpopular long position. To get hedge funds and other special situation operators to buy the shares, you have to entice them with a very high yield. However once you have lent out a stock, if you then decide you want to sell it, you need to carry out a recall, which means the short seller needs to buy it back and return it before you can actually sell it. This means there will be a few days to weeks, when long investors cannot sell, and short sellers have to buy. This creates an environment where a stock can only go one way.

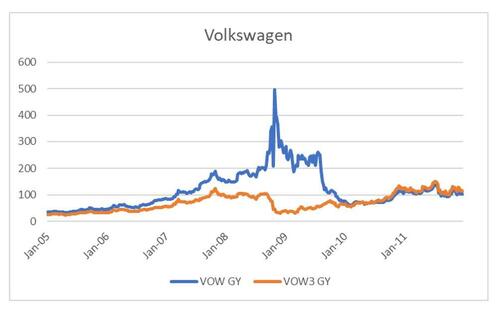

Before the shenanigans with Telsa, AMC and GME, the all-time capital destruction short squeeze was Volkswagen. The Volkswagen short squeeze was organized by the management of the company, who had quietly managed to secure control of a large amount of VOW GY shares (voting shares). VOW attracted a large number of shorts, due to a) it was the middle of the GFC, and b) it was trading at an all-time high relative to its more liquid preference shares. German listed stocks do not provide short interest ratio as readily as US listed stocks, but the cost of borrow prior to the spike was around 4% (I had a small position at the time, but fortunately all my other shorts were making money so was not a career ending squeeze for me – unlike many other funds).

Hence when I talk about never short a stock with 2% borrow, I am referring only to the cost of borrowing the stock to short sell, and not its short interest ratio. And I do this as I have yet to a stock with a 2% borrow have a career ending short squeeze.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 12/01/2022 – 10:21

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/o1YdjWf Tyler Durden