Why The Equity Market Need Not Fear A Recession

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The stock market may show greater resilience than usual through the next recession.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence,” said F. Scott Fitzgerald, “is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time.”

Where investors should employ this more than anywhere else is in the possibility that even in the event of a recession, stocks do not face as severe a selloff as they have in the past.

The recession obsession stems from the damage it can do to portfolios. The S&P sells off an average of 5% before a slump starts, and can go on to fall another 30% during the downturn itself. But price action suggests that this time stocks may not fare so badly.

First, though, recession risk is definitively rising, even if it isn’t a dyed-in-the-wool certainty.

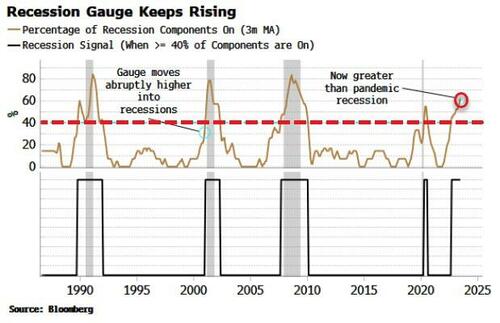

One of the most comprehensive and reliable leading indicators of a recession is the Recession Gauge. It is made up of 14 recession sub-indicators that capture a wide array of market and economic-based conditions. The gauge triggers when at least six of them activate, signaling a recession in the next 3-9 months.

As the chart below shows, the gauge triggered in September, with the number of sub-indicators continuing to rise. The latest activated last week after Friday’s employment data showed a further decline in temporary help services, one of the most leading parts of the job market. This took the number of sub-indicators consistent with a recession to nine out of 14, the highest since 2008.

Last Friday’s employment data should not be taken taken as a sign a recession is likely to be avoided. Payrolls may have come in significantly stronger than expected, but data from the household survey showed the largest one-month rise in the unemployment rate since April 2020 (at the peak of lockdown).

Further, payrolls continued their deviation from household-survey employment, implying that almost two million more jobs than employees have been created since March last year. This is not a convincing sign of a robust employment market, while also leaving payrolls exposed to sharp declines as gig workers quit multiple jobs to take on one full-time position.

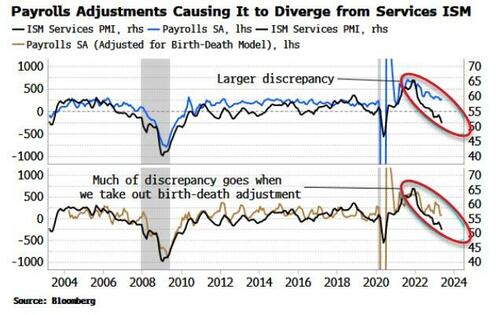

The two-million divergence is similar to the number of jobs the birth-death model has added to payrolls over the same period. The model is supposed to capture the net number of new jobs not picked up in the sampling period from newly formed and dying companies, and has been adding considerably more jobs since the pandemic.

The model may be right, but it becomes increasingly salutary to question it when payrolls starts to become an outlier. Notably, payrolls data has been diverging from the weakening ISM services (with Monday’s release confirming this trend). But subtracting the birth-death model’s adjustment from payrolls shows a much smaller discrepancy between the two series. (Strictly speaking we should use non seasonally-adjusted payrolls for the adjustment but this introduces other unwanted seasonal effects).

So if recessions are bad news for stocks and the risk of one occurring soon is heightened, why should this time be different?

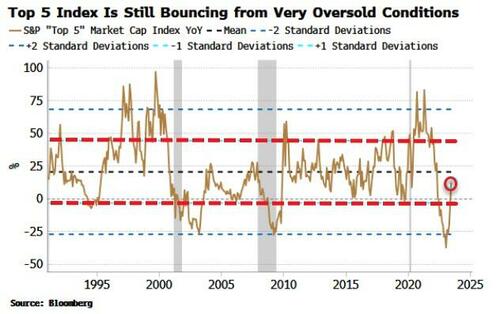

Firstly, extremely narrow breadth can often be a sign of further strength.

Whenever the “Top 5” index (the top five S&P stocks by market cap) is outperforming the broad index by as much as it is today, it typically leads to marked outperformance in the S&P over the following three, six and 12 months.

That may be even more so today as the Top 5 index is still in the process of bouncing from very oversold conditions. The Top 5 shows overshooting/undershooting tendencies and looks to be in the process of overshooting to the upside, while the index of the residual, lowest market-cap stocks remains oversold and therefore has the potential to rally.

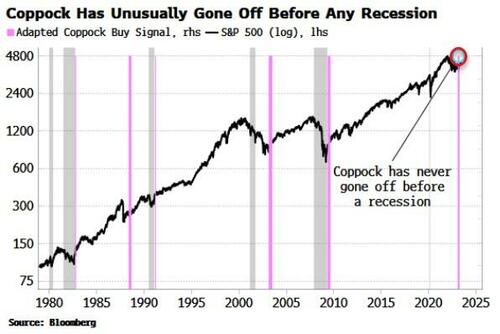

Secondly, broad price action is very constructive. I noted in April that a very reliable signal of long-term returns, the Coppock, triggered in March. It is usual for this signal to flash after a recession, or on occasion in the middle of the cycle (following the 1987 crash). It has never gone off immediately before a recession (assuming we get one very soon, which as above the Recession Gauge anticipates).

The greatest long-term risk for stocks is likely not a recession, but a resurgence in inflation (increased Treasury issuance after the debt-ceiling détente has the potential to create short-term weakness).

High-duration sectors such as tech are leading the advance, and are the most inflation-sensitive. But given China’s stall, the general disinflationary trend shouldn’t be disrupted over the next 3-6 months.

Cognitive dissonance is therefore advised, as equities have the potential to remain supported in the medium term, even if the lurking bogeyman of a recession strikes.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 06/06/2023 – 10:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/N6gBf3y Tyler Durden