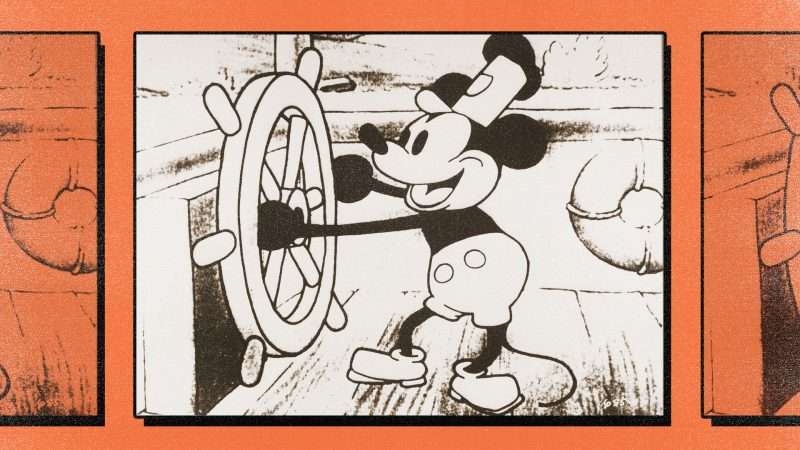

The copyright on Mickey Mouse expires today, meaning The Walt Disney Company no longer has the exclusive rights to the character. Does this mean you can put Mickey in your own cartoon? Not exactly.

Under current law, works released between 1924 and 1978 are copyrighted for 95 years. As a result, the thousands of works copyrighted in 1928 enter the public domain today, meaning anyone can use or reprint them without permission. That includes books like D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and films like Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus. But the most high-profile addition is Steamboat Willie, the animated short that marked the debuts of both Mickey and his longtime paramour, Minnie.

The cartoon depicted Mickey Mouse working aboard a steamboat, making music, and vexing the boat’s captain, a large cat named Pete. The slapstick humor, anthropomorphized animals, and objects of later Disney works are present, although Mickey is much more mischievous—the antagonistic dynamic with a giant cat is more reminiscent of Tom & Jerry cartoons than the Mickey Mouse familiar to modern audiences.

The seven-minute film was revolutionary: It was the first cartoon to feature synchronized sound—rather than just a silent film with background music—and audiences loved it. Mickey Mouse spawned a franchise that over the following century would earn more than $80 billion and make Disney one of the most powerful media companies on the planet.

Losing out on its rodential cash cow would be a huge blow, and Disney jealously guarded its creation. When Steamboat Willie premiered in November 1928, U.S. law dictated that it would enter the public domain no later than 1984. But two different laws, one passed in 1976 and another in 1998, extended the maximum copyright term, each by twenty years. Each law passed after strenuous lobbying by Disney: The latter statute, the Copyright Term Extension Act, has been derisively referred to as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act.

Today’s expiration implies that Disney was either unable to secure another extension or unwilling to try. In recent years, Republican lawmakers have signaled their unwillingness to extend copyright law any further on Disney’s behalf. Sen. Josh Hawley (R–Mo.) even introduced the Copyright Clause Restoration Act of 2022, which would cap copyright terms at a maximum of 56 years—notably, the same term in effect when Walt Disney first released Steamboat Willie.

But this doesn’t mean that Mickey is completely free. The copyright that expires today only applies to Mickey Mouse as he first appeared: rat-like and mischievous, with pupil-less eyes and no gloves. All other interpretations, introduced later—including the magnanimous Mickey who greets visitors to Disney theme parks dressed in a bow tie and tails, with white gloves and human-like eyes and facial features—remain under lock and key.

“We will, of course, continue to protect our rights in the more modern versions of Mickey Mouse and other works that remain subject to copyright,” a Disney spokesperson told the Associated Press in a statement.

And while Mickey may lose copyright status, he will remain Disney’s exclusive trademark. According to Jennifer Jenkins, director of Duke University’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain, any new use of Mickey must ensure that it is unlikely to be mistaken for a Disney product. “There might be a risk of confusion if you use Mickey as a brand identifier on the kind of merchandise Disney sells,” Jenkins writes. “Consumers may also be confused if Mickey is used in an artistic work in a way that suggests it is a Disney production, for example by appearing as a logo at the beginning of an animation.”

On January 1, 2022, A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh entered the public domain, bringing the characters with it. The following day, wireless company Mint Mobile released a commercial in which actor Ryan Reynolds reads a version of the story. That May, British director Rhys Frake-Waterfield released stills from his film Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey, a horror flick in which Pooh and his sidekick Piglet revert to a feral state and mow down coeds after their human companion Christopher Robin leaves for college.

Just as with Mickey, Frake-Waterfield could only use Milne’s characters as they were depicted in the original book: Pooh was first drawn in his iconic red shirt in 1932, meaning that version of Pooh is still under copyright protection. Characters introduced in later works, like the buoyant Tigger who debuted in 1928’s The House at Pooh Corner, also remained protected. (The House at Pooh Corner also falls into the public domain today, and Tigger is expected to be featured in Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey 2, premiering next month.)

What does all of this mean for Mickey Mouse? What does it matter if one particular version of a cartoon character enters the public domain?

Regardless of the artistic merit of a horror movie about Winnie-the-Pooh—and critics apparently found very little—the public domain is a boon for creative expression, allowing people to use established characters and works in new and inventive ways. Ironically, Steamboat Willie benefited significantly from the public domain. The cartoon made extensive use of the song “Turkey in the Straw,” a familiar tune with uncomfortable racist origins that dates back to the pre-Civil War era.

And “the Mickey character itself is based on such public domain fodder,” Jenkins writes. “His personality and antics drew from silent film stars such as Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks,” as Walt Disney and animator Ub Iwerks acknowledged at the time. Even the cartoon’s title was a reference to the Buster Keaton film Steamboat Bill, Jr., released six months before Steamboat Willie. Since movie titles and personality traits are generally not copyrightable, all of this was fair game when Disney crafted Mickey Mouse.

The post Mickey Mouse Is Now In the Public Domain. Well, Sort Of. appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest https://ift.tt/nMJp5kL

via IFTTT