“We Are Buyers Of Dips”: Wall Street’s Biggest Bear Turns Bullish

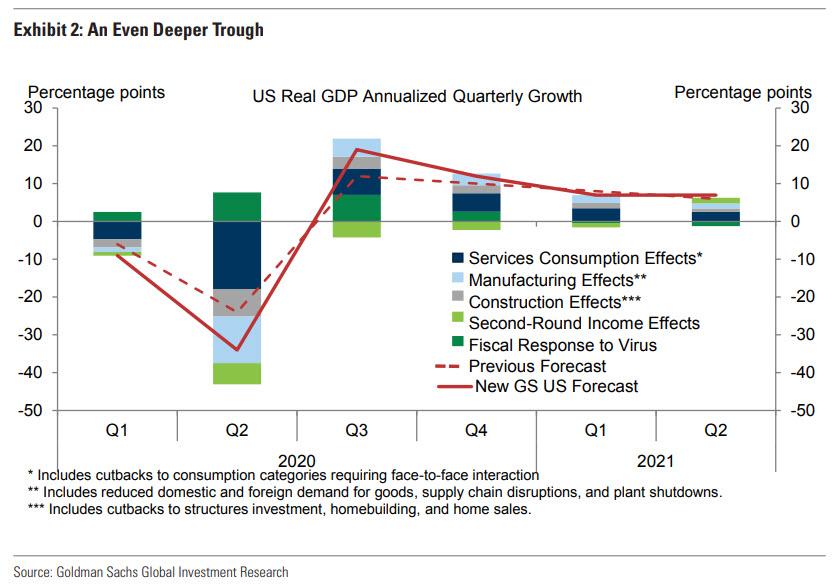

For much of 2019, Morgan Stanley’s chief equity strategist Micheal Wilson issued a weekly sermon of fire and brimstone in his Monday Morning market takes, which contrasted with the euphoric pronouncements by his peers at other banks – most notably Goldman, which in December hilarious declared that the US economy is “structurally less recession-prone today”, which probably explains why three months later the same bank cut its Q2 GDP estimate to -34%…

… earning him the moniker of Wall Street’s biggest bear (a few permabearish exceptions such as Albert Edwards were excluded from the tally), not to mention quite a few angry clients. Then, in November, just as the melt up phase of the post “Not QE” market was kicking in sending stocks to all time highs every single day, Wilson got the proverbial tap on the shoulder, and threw in the towel raising his S&P “bull case” price target to 3,250, however not without a slew of warnings that the most likely outcome was another retest in stocks lower.

In retrospect, Wilson should have held fast to his bearish conviction as the unprecedented March market crisis confirmed he was spot on (even if for different reasons).

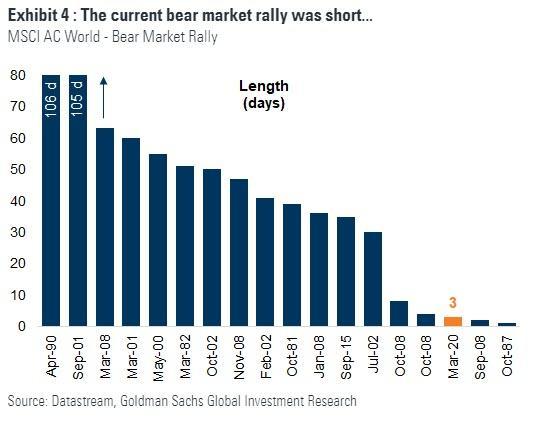

And yet, demonstrating just how fickle Wall Street fates can be, just as Goldman turned beyond bearish, warning today that the recent rally was just a bear market bounce…

… Wall Street’s “biggest bear”, Michael Wilson turned bullish, paraphrasing Michael Hartnett who famously says that “markets stop to panic when officials start to panic”, and in his latest strategy note writes that “crises lead to bailouts and this time it’s extreme given health angle. As a result, the inevitable credit crunch could be truncated this time, leaving us buyers of dips.”

Explaining the reasoning behind his reversal, Wilson first lays out how we got here, noting that “in the past month, we’ve experienced a full bear market (-20%) and full bull market (+20%)” extreme volatility which follows a period of extreme calm during which we observed some of the lowest volatility readings in history.

Then in an appeal to the Austrians inside all of us (by which we mean Zero Hedge readers), Wilson points out that as noted by Hyman Minsky, the onset of a market collapse can be brought on by the reckless speculative activity that defines an unsustainable bullish period – i.e. the Minsky moment.

Sound familiar? If one accepts that 4Q19 was a speculative frenzy driven by liquidity rather than fundamentals, such a conclusion is compelling.

This, incidentally, is Wilson’s – rather subdued – victory lap; it would have been far less subdued had Wilson not turned semi bullish in November, but since it may have been his job or his conviction, we’ll let it slide. That said, Wilson’s argument is spot on, and has to do with the fact that while Covid was the spark for the crisis, the gasoline that was poured on the crash was the unprecedented build up of the trillions in debt over the past decade, that lifted asset prices to their February all time highs…. and the resulting violent unwind. To wit:

Excess leverage explains the ferocity of the decline in risk assets and the economy. While the focus right now is on COVID-19 as the cause of the bear market, the conditions have to be in place for a market and economic crash like we have just experienced.

To Wilson, it is important to acknowledge how and why we got here “as it may help us understand and predict what happens from here” especially since “the necessary conditions for a Minsky-type moment referred to above require leverage in the system.”

So before moving on, Wilson explains that in his view there are two primary areas of excess leverage in this particular episode that have been building for the past decade – corporate credit and the shadow banks.

First on corporate credit.

We have never seen corporate leverage as high as it is now. Much of this credit was added because credit markets have rarely been so inviting to issuers. This is the direct result of the financial repression era orchestrated by central banks during and after the Great Recession. In short, the abnormally low cost of borrowing has encouraged companies to lever up and use this financial leverage to drive better earnings growth in what has been a sluggish economic recovery. Companies are capitalist entities and so they are simply acting in their fiduciary duty to shareholders when they behave in such a manner. Much of this financial arbitrage has been executed via share buybacks, which is now being criticized by members of Congress as they pass the largest fiscal stimulus in history. It’s important to note that low growth is very different from negative growth. Now that we have entered a recession, the corporate bond market knows the risk of default is much greater – hence the dramatic moves we have seen in credit spreads in the past month. As an aside, the correction in stocks really took a turn for the worse when tensions between Russia and OPEC caused a collapse in oil prices. This is what triggered the stress in corporate credit markets, in our view, which contributed significantly to the crash in stocks and the economy. Many acknowledge that credit markets are more important to the functioning of the economy than equity. As bad as the moves were in stocks this month, they were much worse in credit than they were in equities on a risk-adjusted basis.

Second is the shadow banks which are unregulated financial market participants.

Without singling out one particular group, these entities also ballooned in size and scope after the financial crisis. Some of this is due to the easy monetary conditions and low borrowing costs provided by central banks while it’s also due to the fact that the traditional banking system is more tightly regulated, which has allowed many of these entities to get bigger in direct lending type activities. Because the shadow banks are unregulated, they may have become too big, which is why they are now having an outsized impact on financial markets as they lever, like last year,and then de-lever like last month.

Of course, it is hardly news to anyone (at least on this site), that the same factor that crushed the system last time around, is also the same one that led to the current crisis – namely debt. The coronavirus was just the selling catalyst; and once the liquidation feedback loops kicked in and the debt had to be unwound, we got the quad-witching disaster of March 20 when the S&P was trading at levels below Trump’s inauguration. In any case, we compliment Wilson for daring to something which is increasingly frowned upon in the country of “free speech” – and twitter – tell the truth, especially when it is inconvenient. With that in mind, the good news, according to Morgan Stanley, is that the regulated banking system is stronger than normal for this part of the cycle – when we are entering a recession – which means credit should still remain available. The Fed has a viable system to get the capital they are providing to the places that need it most as the economy contracts and cash flows dry up. From that perspective, “this is very different than 2008-09 and one reason we believe the Fed’s extraordinarily aggressive actions to date, which include intervening in the corporate credit markets directly, will ultimately shorten the duration of this recession even if they can’t stop the severity of the slowdown in the very near term.”

And here is another instance of Wilson admirably telling the truth about what the Fed is doing:

They are, in effect, bailing out the bad actors in the corporate credit market, which should truncate the pain for both investors and issuers, and – eventually – the economy.

One final truth:

The fact that a health crisis is now the villain of this recession arguably makes this correction less painful than it would have been otherwise for credit markets, and the shadow banks.

After all one can’t really depose or sue a virus. In fact, one can almost claim that the coronavirus outbreak was perhaps the most “convenient” thing that could have happened to the US financial and debt bubble: by forcing a global economic reset, it gave a carte blanche to triple down on the same debt that crashed the system twice already… and will crash it again.

But not for some time… which is why in its response to the question that is number one among its clients (incidentally the same question posed by Goldman clients), namely “will US equity markets make fresh lows in this bear market”, Wilson answer that his short answer is no “for the major averages and most stocks.” The longer answer is based on several key factors Wilson thinks are unique to this correction:

- 1. Recent lows were made during what can only be described as a forced liquidation bylevered players – aka shadow banks… Both systematic strategies and active managers are now basically “sold out” and have very low risk/leverage at this point. In other words, it’s hard to imagine the kind of liquidation that we just witnessed in March could happen again from these much lower levels of leverage.

- 2. This past week, credit markets stabilized thanks to unprecedented support from the Federal Reserve and other central banks. After the past 10 years, we have no doubt in their resolve to stabilize both the funding and credit markets. Most investors we speak with agree and are actively looking to put capital into IG, Mortgages, Agency, Securitized paper and anything else the Fed has said they will be buying directly. Even high yield has responded positively, which the Fed is not buying. Perhaps the most positive market signal last week was the fact that high yield remained in positive territory on Friday even after equity markets sold off sharply into the close. The weaker US dollar is also a good sign that policy (both monetaryand fiscal) is now viewed as getting ahead of the curve.

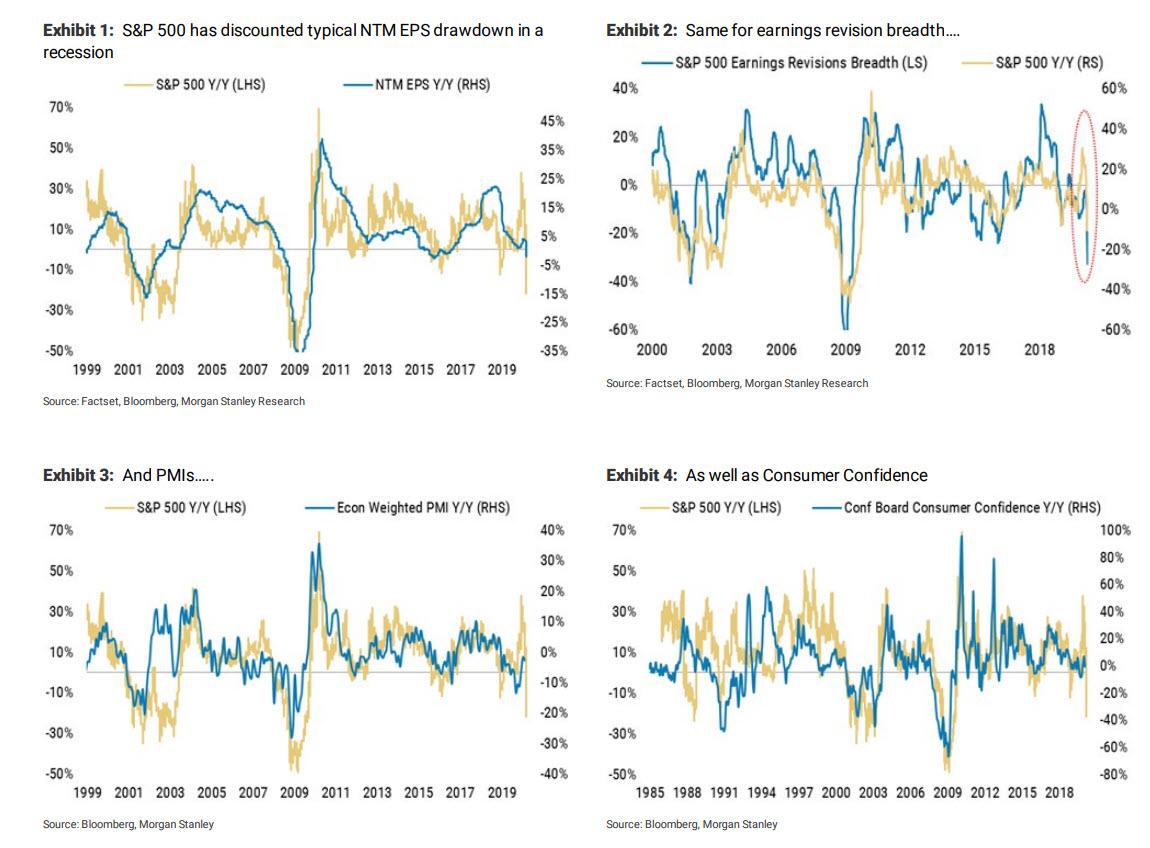

- 3. Economic and earnings data will be grim over the next month, but equity markets may have already discounted these revisions based on valuation and some simple relationships we track. First, the equity risk premium for the S&P 500 got as high as 700bps last Monday; it’s the second-highest level we have on record (2011 was higher post the downgrade of Treasuries to AA). If we look at this from a sector and stock standpoint, we are at all-time highs. We think this suggests the index can hold the old lows even if some of the most favored sectors and stocks do not. As for some simple relationships, we compare the y/y change in the S&P to the y/y change in earnings growth and revisions breadth, PMIs,and consumer confidence. Based on the 20% y/y decline in the S&P 500, a very rare event usually associated with recessions, we think the market has discounted the recessionary economic and earnings data we expect to see next month (Exhibits 1-4). Having said that, it has not discounted a full-blown financial crisis like we experienced in 2008-09.

- 4. Finally, from our hundreds of conversations with clients the past few weeks, there is a strong consensus for lower lows on a retest over the next month or two. While that doesn’t mean the consensus can’t be right, we would remind readers that we never got a retest of the December 2018 lows which happened under a similar type forced liquidation. Time-tested technical tools like retests with a positive divergence may not work as well in a world dominated by oversized shadow banks which have become the marginal buyer/seller that really sets the price in the short term

Wilson’s bullish conclusion is also the reason why the most bearish strategist on Wall Street just may be the most bullish one:

… rarely do markets become so dislocated as they have in the past month, but such are the conditions from which great investment opportunities are born. We have been less bullish than most over the past several years under the view we were headed toward the end of the cycle. While we never know what will tip us into a recession, the conditions for one have to be in place and the excesses in the credit world were exhibit A in that regard. Now that we are here, we would like to remind readers that bear markets end with recessions, they don’t begin with them.

And, ironically, this means that MS is now flipped with Goldman, which has turned bearish and is loathe to recommend buying here, anticipating another leg lower after the bear market rally ends, while Wilson and Morgan Stanley are now the most bullish bank (with the possible exception of JPMorgan):

Given that most stocks have been in a bear market for two years or longer, we recommend investors start buying stocks now because we cannot be sure if the next pull back will lead to lowers lows or not given we already experienced forced liquidation. Bottom line, we believe 2400-2600 on the S&P 500 will prove to be very good entry points for those with a time horizon of 6-12 months.

We’ll be sure to check back in 6-12 months. And speaking of “checking back”, last July another Wall Street bull, JPM’s Marko Kolanovic thought he spotted a similar bullish trade in the collapse of value stocks which he thought were a “once in a decade” buying opportunity while low vol/growth stocks were to be shorted. ALmost a year later, we can safely say that anyone who put on this “once in a decade” trade, which has seen the total obliteration of value stocks, has now been fired. We can only hope that Wilson doesn’t follow Kolanovic’s fate.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 03/31/2020 – 14:35

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/39wx36w Tyler Durden