Submitted by Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World blog,

The Peak Oil story got some things right. Back in 1998, Colin Campbell and Jean Laherrère wrote an article published in Scientific American called, “The End of Cheap Oil.” In it they said:

Our analysis of the discovery and production of oil fields around the world suggests that within the next decade, the supply of conventional oil will be unable to keep up with demand.

There is no single definition for conventional oil. According to one view, conventional oil is oil that can be extracted by conventional methods. Another holds it to be oil that can be extracted inexpensively. Other authors list specific types of oil that require specialized techniques, such as very heavy oil and oil from shale formations, that are considered unconventional.

Figure 1 shows the growth in unconventional oil supply for three parts of the world:

- Oil from shale formations in the US.

- Oil from the Oil Sands in Canada.

- Oil characterized as unconventional in China, in a recent academic paper of which I was a co-author. (Temporarily available for free here.)

Figure 1. Approximate unconventional oil production in the United States, Canada, and China. US amounts estimated from EIA data; Canadian amounts from CAPP. Oil prices are yearly average Brent oil prices in $2015, from BP 2016 Statistical Review of World Energy.

Oil prices in 1998, which is when the above quote was written, were very low, averaging $12.72 per barrel in money of the day–equivalent to $18.49 per barrel in 2015 dollars. From the view of the authors, even today’s oil prices in the low $40s per barrel would be quite high. Since the above chart shows only yearly average prices, it doesn’t really show how high prices rose in 2008, or how low they fell that same year. But even when oil prices fell very low in December 2008, they remained well above $18.49 per barrel.

Clearly, if oil prices briefly exceeded six times 1998 prices in 2008, and remained in the range of six times 1998 prices in the 2011 to 2013 period, companies had an incentive to use techniques that were much higher-cost than those used in the 1998 time-period. If we subtract from total crude oil production only the production of the three types of unconventional oil shown in Figure 1, we find that a bumpy plateau of conventional oil started in 2005. In fact, conventional oil production in 2005 is slightly higher than the later values.

Figure 2. World conventional crude oil production, if our definition of unconventional is defined as in Figure 1.

I would argue that far more crude oil production was enabled by high oil prices than I subtracted out in Figure 2. For example, Daqing Oil Field in China is a conventional oil field, but greater extraction has been enabled in recent years by polymer flooding and other advanced (and thus, high-cost) techniques. In the academic paper referenced earlier, we found that the amount of unconventional oil extracted in China in 2014 would be increased by about 55%, if we broadened the definition of unconventional oil to include oil made available by polymer flooding in Daqing, plus some other types of Chinese oil extraction that became more feasible because of higher prices.

Clearly, this same kind of shift to more expensive extraction methods has occurred around the world. For example, Brazil has been attempting to extract oil from below the salt layer of the ocean using advanced techniques. According to this article, Brazil’s “pre-salt” oil production was expected to exceed 600,000 barrels per day by the end of 2014. This oil should count, in some sense, as unconventional oil.

Massive investments in the Kashagan Oil Field in Kazakhstan were enabled by high oil prices. Some initial production began, but was discontinued, in September 2013. Production is expected to resume in October 2016.

There are clearly many smaller fields where higher extraction was made possible by high oil prices that allowed oil companies to utilize more advanced techniques. Deepwater drilling also became more feasible because of higher prices. Another example is Russia, which is reported to have heavy oil extraction that would not be commercially feasible if oil prices were below $40 to $45 per barrel. If we were to add up all of the extra oil production in many areas of the world that was enabled by higher prices, the total amount would no doubt be substantial. Subtracting this higher estimate of unconventional oil in Figure 2 (instead of the three-country total) would likely result in more of a “peak” in conventional oil production, starting about 2005.

Thus, if we think of conventional oil production as that which is possible at low oil prices, the forecast by Colin Campbell and Jean Laherrère was pretty much correct. Production of conventional oil did seem to peak about 2005 or shortly thereafter. We simply don’t have the data to estimate how much we could have extracted, if oil prices had remained low. Furthermore, oil prices did rise substantially, relative to 1998 prices, making Campbell’s and Laherrère’s forecast of higher prices correct.

I suppose that we could even say that if conventional oil were all that we had in 2005 and subsequent years, supply would have fallen far short of demand, based on Figure 2. This last statement is somewhat debatable, however, because there would have been other feedbacks, as well. It is possible that if total supply were very short, oil prices would have spiked to an even higher level than they really did. The resulting recession would likely have brought prices down, and temporarily brought demand back in line with supply. If prices had stayed low, there might have been a second round of shortages, with an even greater supply problem. This, too, might have been resolved by another price spike, quickly followed by another recession that brought world demand back down to the level of supply.

Of course, conventional crude oil isn’t the only type of liquid fuel that we use. When we add all of the pieces together, including substitutes, what we find is that since 1998, broadly defined oil production (“liquids”) has been rising quite rapidly.

Figure 3. World Liquids by Type. Unconventional oil is from Exhibit 1. Conventional oil is total crude oil from EIA, and other amounts are estimated from EIA International Petroleum Monthly amounts through October 2015. (EIA’s category “Other Liquids” is referred to as Biofuels in Figure 3, since this is its primary component. Other liquids also include coal and gas to liquids and other small categories.)

In fact, since 2005, Figure 4 shows that the single highest year of growth in oil production (broadly defined) was 2014, with 2.47 million barrels per day. (This is based on crude oil data from EIA Beta Report Table 11.b, plus values for other liquids from EIA’s International Energy Statistics. Annual amounts for 2015 were estimated based on data through October.)

Figure 4. Increase over prior year in total oil liquids production, based on EIA data. 2015 other liquids amounts estimated based on data through October 2015.

Figure 4 shows that the increase in oil supply in 2015 is almost as high as in 2014. The 2005 to 2015 period shown indicates a lot of “ups and downs.” The only two high years in a row are 2014 and 2015. This would seem to be at least part of our “oil glut” problem.

Exactly by how much oil production needs to increase to stay even with demand depends upon price–the higher the price, the smaller the quantity that buyers can afford. At a price of $100 per barrel, a reasonable guess might be that about 1 million barrels per day in consumption might be added. If categories other than crude oil are increasing by an average of 440,000 barrels per day, per year (based on data underlying Figure 4), then crude oil production only needs to increase by 560,000 barrels per day to provide an adequate supply of fuel on a total liquids basis.

If production of crude oil is actually increasing by more than 2.0 million barrels per day when only 560,000 barrels per day are needed at a price level of $100 per barrel, clearly something is badly out of balance. According to EIA data, the countries with the five largest increases in crude oil production in 2015 were (1) US 723,000 bpd, (2) Iraq 686,000 bpd, (3) Saudi Arabia 310,000 bpd, (4) Russia 146,000 bpd, and (5) UK 106,000 bpd. Thus, US and Iraq were the biggest contributors to the global glut in 2015.

What Is Going Wrong?

Not only did a lot of people hear the Peak Oil story, a great many responded at once. Governments added requirements for more efficient vehicles. This tended to lower the quantity of additional oil supply needed. At the same time, governments added mandates for the use of biofuels, also reducing the need for crude oil. Arguably, the US-led Iraq war, which began in 2003, was also about getting more crude oil.

Oil companies also rushed in and developed oil resources that might be profitable at a higher price. These new developments often take more than ten years to produce oil. Once companies have started the long path to development, they are unlikely to stop, no matter how low oil prices drop.

It is becoming apparent that if oil prices can be raised to a high enough level, a lot more oil is available. Figure 5 shows how I see this as happening. We start at the top of the triangle, where there is a relatively small quantity of inexpensive oil, and we gradually work toward the expensive oil at the bottom.

The amount of oil (or for that matter, any other resource) isn’t a fixed amount. If the price can be made to rise to a very high level, the quantity that can be extracted will also tend to rise–in fact, by a rather large amount. The “catch” is that wages for the vast majority of workers don’t rise at the same time. As a result, goods made with high-priced oil soon become too expensive for workers to afford, and the economy falls into recession. The result is prices that fall below the cost of production. Thus, the limit on oil supply is not the amount of oil in the ground; instead, it is how high oil prices can rise, without causing serious recession.

While wages don’t rise with spiking oil prices, increasing debt can be used to hide the problem, at least temporarily. For example, cars and homes become less affordable with higher oil prices, since oil is used in making them. If governments can lower interest rates, monthly payments for new homes and cars can be lowered sufficiently that new car and home sales don’t fall too far. Eventually, this cover-up reaches limits. This happens when interest rates start turning negative, as they now are in some parts of the world.

Thus, by ramping up buying power with low interest rates and more debt, governments were able to get oil prices to stay above $100 per barrel for long enough for producers to start adding production that might be profitable at that price. Unfortunately, the amount of additional oil demand isn’t really very high at that price. So, instead of running out of oil, we ran into the reverse problem–too much oil relative to the amount that the world economy can afford when oil prices are $100+ per barrel.

The attempt by governments to fix the oil shortage problem didn’t really work. Instead, it led to the opposite mismatch from the one we were expecting. We got an oversupply problem–a problem of finding enough space for all our extra supply (Figure 6). Unless we have infinite storage, this pattern clearly cannot continue forever.

Eventually, this oversupply problem is likely to result in “mother nature” cutting off oil production in whatever way it sees fit–oil prices dropping to close to zero, bankruptcies of oil companies, or collapses of oil exporters. With lower oil supply, we can expect recession.

Misunderstanding the Real Problem

In the early 2000s, the story that Peak Oilers came up with (or perhaps the way it was interpreted in the press) was that the world was “running out” of conventional oil, and that this would lead to all kinds of problems. Oil prices would rise very high, and oil depletion would take place over a long period, as shown in a symmetric Hubbert Curve. As a result, at least small quantities of additional energy products with high “Energy Returned on Energy Invested” (EROI) were needed to supplement the energy products that would be produced based on the slowly depleting Hubbert Curve. Our oil supply problems were viewed as a unique situation, calling for new and unique solutions.

In my view, this story came about through over-reliance on models that likely were accurate for some purposes, but not for the purpose that they later were being used. One of these over-extended models was the supply and demand curve of economists.

Figure 7. From Wikipedia: The price P of a product is determined by a balance between production at each price (supply S) and the desires of those with purchasing power at each price (demand D). The diagram shows a positive shift in demand from D1 to D2, resulting in an increase in price (P) and quantity sold (Q) of the product.

This model “works” when the goods being modeled are widgets, or some other type of goods that does not have a material impact on the economy as a whole. Substituting high-priced oil for low-priced oil tends to make the economies of oil importing countries contract. This effect indirectly reduces demand (and thus prices) for many products (not just oil), an impact not considered in the simplified Supply and Demand model shown in Figure 7. Also, the very long lead times of the oil industry are not reflected in Figure 7.

Two other models that were used beyond the limits for which they were originally designed were the Hubbert Curve and the 1972 Limits to Growth model. Both of these models are suitable for determining approximately when limits might be hit. Even though Peak Oilers have believed that these models can accurately determine the shape of the decline in oil supply and in other variables after reaching limits, there is no reason why this should be the case. I talk about this problem in my recent post, Overly Simple Energy-Economy Models Give Misleading Answers. Thus, for example, there is no reason to believe that 50% of oil will be extracted post-peak. This is only an artifact of an overly simple model. The actual down slope may be much steeper.

The Real Story of Resource Limits that We Are Reaching

Instead of the scenario envisioned by Peak Oilers, I think that it is likely that we will in the very near future hit a limit similar to the collapse scenarios that many early civilizations encountered when they hit resource limits. We don’t think about our situation as being similar to early economies, but we too are reaching a situation of decreasing resources per capita (especially energy resources). The resource we are most concerned about is oil, but there are other resources in short supply, including fresh water and some minerals.

Research by Joseph Tainter and by Peter Turchin indicates that some of the issues involved in previous resource-based collapses are the following:

Growing Complexity. Citizens who discovered they were reaching resource limits typically tried to work around this problem. For example, hunter-gatherers turned to agriculture when their population grew too large. Later, civilizations facing limits added irrigation to raise food output, or raised large armies so that they could attack neighboring countries. Making these changes required greater job specialization and more of a hierarchical system–two aspects of growing complexity.

This increased complexity used part of the resources that were in short supply, since people at the top of the hierarchy were paid more, and since building new capital goods (today’s example might be wind turbines and solar panels) takes resources that might be used elsewhere in the economy. Eventually, growing complexity reaches limits because costs rise faster than the benefits of growing complexity.

Growing Wage Disparity. With growing complexity, wage disparity became more of a problem.

I have described this problem as “Falling Return on Human Labor Invested.” Ultimately, this seems to be a major cause of collapse. Workers use machines and other tools, so this return on human labor has been leveraged by fossil fuels and other energy resources used by the system.

Spiking Resource Prices. Initially, when there is a shortage of food or fuel, prices are likely to spike. A major impediment to long-term high prices is the large number of people at the bottom of the hierarchy (Figure 8) who cannot afford high-priced goods. Thus, the belief that prices can permanently rise to high levels is probably false. Also, Revelation 18: 11-13 indicates that when ancient Babylon collapsed, the problem was a lack of demand and low prices. Merchants found no one to sell their cargos to; no one would even buy human slaves–an energy product.

Rising Debt. Debt was used to enable complexity and to hide the problems that people at the bottom of the resource triangle were having in purchasing goods. Ultimately, increased debt was not successful in solving the many problems the economies faced.

Ultimately, Failing Governments. Governments need resources for their purposes, whether hiring armies or making transfer payments to the elderly. The way governments get their share of resources is through the use of tax revenue. When people at the bottom of the hierarchy were cut out of receiving adequate resources (through low wages), the amounts they could afford to pay in taxes fell. Governments would sometimes collapse directly from lack of tax revenue; other times collapses occurred because governments could no longer afford large enough armies to defend their borders.

Ultimately, Falling Population. With low wages and governments requiring higher tax levels to fund their programs, people at the bottom of the hierarchy found it difficult to afford adequate nutrition. They became more susceptible to plagues. Loss of battles to neighboring countries could at times play a role as well.

Lessons We Should Be Learning

Even if we made it past peak conventional oil, there is likely a different, very real collapse ahead. This collapse will occur because the economy cannot really afford high-priced energy products. There are too many adverse feedbacks, including increasing wealth disparity and the likelihood of not enough revenue for governments.

We can’t count on long-term high prices. The idea that fossil-fuel prices will gradually rise, and because of this, we will be able to substitute high-priced renewables, seems very unlikely. In the United States, our infrastructure was mostly built on oil that cost less than $20 per barrel (in 2015 dollars). We know that with added debt and greater complexity, we were temporarily able to get oil to a high-price level, but now we are having a hard time getting the price level back up again. We really don’t know how high a price the economy can afford for oil for the long term. The top price may not be more than $50 per barrel; in fact, it may not be more than $20 per barrel.

We need to look for inexpensive replacements for both oil and electricity. Many substitutes are being made to produce electricity, since indirectly, electricity might act to replace some oil usage. There is considerable confusion as to how low these prices need to be. In my opinion, we can’t really raise electricity prices without pushing economies toward recession. Thus, we need to be comparing the cost of proposed replacements, including long distance transport costs and the cost of adjustments needed to match electric grid requirements, to wholesale electricity prices. In both the US and Europe (Figure 9), this is typically less than 5 cents per kWh. (In Figure 9, “Germany spot” is the wholesale electricity price in Germany–the single largest market.) At this price level, producers need to be profitable and to pay taxes to help support governments.

Figure 9. Residential Electricity Prices in Europe, together with Germany spot wholesale price, from http://ift.tt/2ac0xvy

Replacements for oil need to be profitable and be able to pay taxes, at currently available price levels–low $40s per barrel, or less.

We need to be careful in aiming for high-tech solutions, because of the complexity they add to the system. High-tech solutions look wonderful, but they are very difficult to evaluate. How much do they really add in costs, when everything is included? How much do they add in debt? How much do they add (or subtract) in tax revenue? What are their indirect effects, such as the need for more education for workers?

We need to be alert to the possibility that solar PV and most wind energy may be energy sinks, rather than true energy sources. The two hallmarks of providing true net energy to society are (1) being able to provide energy cheaply, and (2) being able to provide tax revenue to support the government. When actually integrated into the electric grid, electricity generated by wind or by solar generally requires subsidies–the opposite of providing tax revenue. Total costs tend to be high because of many unforeseen issues, including improper siting, long-distance transport costs, and costs associated with mitigating intermittency.

Unless EROI studies are specially tailored (such as this one and this one), they are likely to overstate the benefit of intermittent renewables to the system. This problem is related to the issues discussed in my recent post, Overly Simple Energy-Economy Models Give Misleading Answers. My experience is that researchers tend to overlook the special studies that point out problems. Instead, they rely on the results of meta-analyses of estimates using very narrow boundaries, thus perpetuating the myth that solar PV and wind can somehow save our current economy.

Too much debt, and too low a return on debt, are likely to be part of the limit we will be reaching. Investment in complexity requires debt, because complexity requires capital goods such as wind turbines, solar panels, computers and the internet. The return on this additional debt is likely to drop lower and lower, as complex solutions are added that have less and less true value to society.

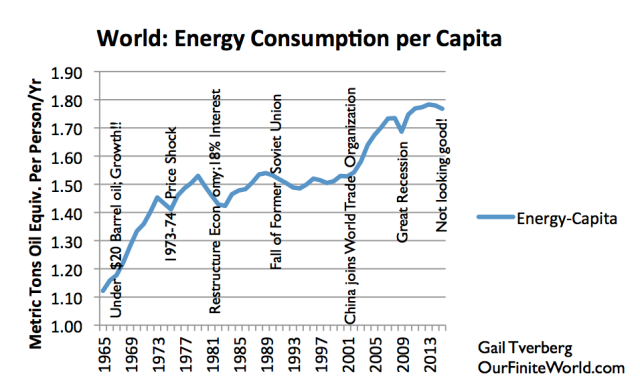

We need to remember that as far as the economy is concerned, it is total consumption of energy resources that is important, not just oil. Wages reflect the leveraging impact of all energy sources, not just oil. If energy consumption per capita is rising, more and better machines can help raise output per capita, making workers more productive. If energy consumption per capita is falling, the world economy is likely moving in the direction of contraction. In fact, we may be headed in the direction of early economies that eventually collapsed.

When we look at the data, we see that world energy consumption per capita appears to have peaked about 2013. In fact, the big drop in oil and other commodity prices began in 2014, not long after energy consumption per capita hit a peak.

Figure 10. World energy consumption per capita, based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2105 data. Year 2015 estimate and notes by G. Tverberg.

The world seems to have hit peak coal, because of low coal prices. In fact, falling coal consumption seems to be the cause of falling world energy consumption per capita. Whether or not most people regard coal highly, coal is pretty much essential to the world economy. A recent decrease in coal consumption is what is pulling world energy consumption per capita down. We do not have any other cheap fuel to make up the shortfall, suggesting that our current downturn in energy consumption (shown in Figure 10) may be permanent.

We should not be surprised if the financial problems that the world is now encountering will eventually resolve badly. This seems to be how the Peak Oil story will finally play out. Without rising energy per capita, the world economy tends to shrink. Without economic growth, it becomes very difficult to repay debt with interest. Wealth disparity becomes more and more of a problem, and it becomes increasingly difficult for governments to collect enough revenue to support their needs. Our problems begin to look more and more like those of earlier economies that hit resource limits, and eventually collapsed.

via http://ift.tt/2bdw2ry Tyler Durden