On one hand the US shale industry has never had it better: following dramatic technological and efficiency improvements in recent years, US oil output is not only at an all time high at 11.9MMb/d, but is the highest of any OPEC or non-OPEC nation in the world. Oil production is so high, in fact, that as of October 2018, the US is now energy independent. Alas, this production glut blessing is also a curse, and according to one industry titan, US production growth could slow by as much as half this year.

Continental Resources’ Harold Hamm said that shale growth could decline by as much as 50% this year compared to 2018, OilPrice reported. Hamm said that a lot of shale E&Ps are trying to keep spending within cash flow. This newfound mantra of capital discipline has been imposed on the shale industry after a decade or so of a debt-fueled drilling frenzy.

“Producers have become more disciplined in their approach to capex,” Hamm said at the Argus Americas Crude Summit in Houston this week. “Several years back growth was a huge consideration. That consideration has been much less. The peak consideration now has been — are you overspending cash flow. Are you living within cash flow?”

The signs of a shale slowdown have been mounting. The rig count fell sharply in recent weeks. Production growth has already begun to slow. Schlumberger, the world’s largest oilfield services company, has warned that it is already seeing shale companies pulling back on drilling activity.

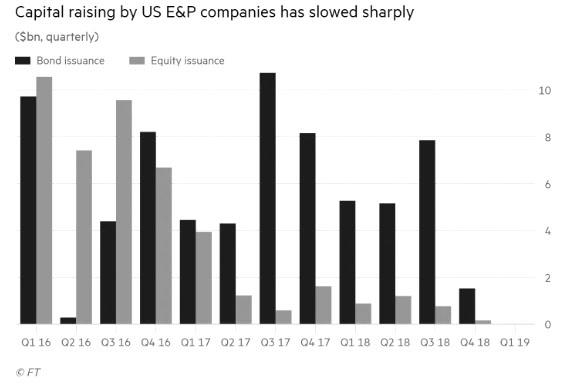

Meanwhile, even though the broader junk bond market has thawed, and new bond deals are once again coming to market, the same is not true for US energy companies. In fact, companies in the E&P sector have not held a single bond sale since the start of November, according to Dealogic, while share sales have also slowed. The data suggest that after a record-breaking boom in US oil output in 2018, growth will be weaker this year… much weaker if Hamm is correct.

Recently the US government’s Energy Information Administration forecast that between December 2018 and December 2019, US crude production will rise by about 500,000 barrels a day. That would represent a sharp slowdown from growth of 1.8m b/d over the previous 12 months.

Of course, for much of the past decade the US shale industry relied heavily on debt to finance its growth, with exploration and production companies raising about $300bn from bond issuance over the past 10 years. However, as crude prices started to slide last October, that source of capital was choked off, with just three bond sales by exploration companies that month, and none at all since November, according to the FT.

Ken Monaghan, co-head of high yield at fund manager Amundi Pioneer said the rise in exploration and production companies’ debt yields had put off potential borrowers, with spreads over US Treasury bonds climbing from 3.9 to 7.5% at their peak before settling back to about 5.9% this year.

“No one wanted to issue debt unless they had to,” Mr Monaghan said. “At the peak, they would have been looking at yields of about 10.25 per cent. That’s awfully expensive.”

But the best place to observe the crash about to hit the E&P sector, is not the E&P sector at all, but the private equity world where firms spent tens of billions in past years to gobble up assets, only to now fund themselves struggling to find buyers for their holdings in the shale patch as listed drillers face mounting pressure to curb spending, executives gathering in Houston said quoted by Bloomberg.

Those long-term investors – all of whom own assets they hope to sell when they’re “ripe” – are holding them for longer, lowering their expectations for returns and seeking mergers for their portfolio companies because of a lack of cash buyers, executives said Thursday at the Private Capital Conference in Houston.

“How many versions of ‘crap’ can we come up with to talk about the A&D market?” said a disgusted Chuck Yates, managing partner at Kayne Anderson Capital referring to the acquisitions and divestitures, or rather lack thereof, in the oil industry. “It’s just horrible. It’s terrible out there.“

Whereas in previous years, the natural buyers of PE energy holdings were listed oil and gas producers, the drop in crude prices has not only led to a drought in the high yield bond market but, combined with investor demands for them to conserve cash, has diminished buyers’ appetites for deals.

“There’s an inability to exit,” said George McCormick, co-founder of Outfitter Energy Capital, speaking about private equity oil and gas holdings as a whole. “The engine on the train is really public companies buying assets from privately backed companies. But public companies aren’t buying today.”

Low oil prices, and thus declining cash flow even as capital spending needs continue to rise, is not the only problem: the other major concern is whether there is oversupply, and how many of the E&P assets currently for sale would be viable one or two years from now, should oil prices fail to rebound. Add to this the bitter memories of 2015 when dozens of PE-sponsored energy names filed for bankruptcy, and one can see why “it’s terrible out there.”

On the face of it, 2018 was a strong year for deals in U.S. energy but many of the biggest transactions, such as Concho Resources’ $7.6 billion purchase of RSP Permian were mostly stock deals. Private equity managers typically prefer their companies to be purchased for cash so they can return the proceeds to their own investors.

That’s a problem: “There are no cash bids coming through,” said Robert Cabes, head of investment management at Intrepid Financial Partners; there is another problem: “There’s a lot of equity that is part of these transactions.” Alas, to monetize that equity it would require selling a major chunk of it, and in a world in which most investors are “buy and hold”, any such attempt to test the market could result in a sharp repricing lower of the already beaten down energy sector.

In the early stages of the U.S. shale boom, companies could buy drilling rights and flip to larger rivals for a handsome profit. Those days are gone, with many companies now being kept private as the “greater fools” have suddenly disappeared, now that funding is increasingly scarce.

That means private equity firms increasingly need to think “strategically” and tap a different kind of management team, one with more operational experience, Stuart Page, managing director at Carlyle, told Bloomberg.

“You need to have the confidence that they can run a development program for five years or more. You can’t flip and get your payback quickly” he said.

The lack of natural buyers has also resulted in a familiar phenomenon within PE land – the infamous hot potato, where leading private players to buy and sell companies to each other, according to Liberty Mutual’s Avtar Vasu.

McCormick said Outfitter’s last three exits have been sales to private players, with two of those private equity firms. Vasu is currently selling an investment to a fellow private buyer because “the public markets are not there,” he said.

And with private equity no longer looking to buy but merely focused on liquidating existing assets in an increasingly uncertain environment, the entire sector has suddenly found itself bidless as the “greater fools” have finally disappeared. .

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2FYGX5J Tyler Durden