Love him or hate him, JPMorgan’s head quant, Marko Kolanovic has a facility and efficiency with words, able to say just what is needed and rarely more, which is naturally a great skill in a time when traders and investors are already bombarded with non-stop information and newsflow, and instead of reading rambling, post-modernist essays would much rather see 2-3 bullet points that get to the point and cover what needs to be covered.

And in this vein, Kolanovic’s recent recap of the key forces that led to the December market rout, while inaccurate, was at least refreshingly concise, to wit:

Fake and real media, domestic political opposition, and foreign geopolitical adversaries welcomed these policies and the instability created in foreign relations, the business community, and financial markets. We hope that some of this negative impact can be reversed, based on the recent progress made at the G20. Trade resolution could provide a much needed boost to equity valuations in 2019.

We brings this because while Kolanovic may be concise, his Deutsche Bank quant peer, Aleksandar Kocic – who according to some, surely himself, is the second coming of James Joyce and if his employer does eventually go tits up he can at least write a 5,000 page book which doubles down as a post-modernist philosophy and linguistics textbook – is not.

And whereas Kolanovic was at least succinct enough to blame recent market volatility on “fake news” in general (and “specialized websites that mass produce a mix of real and fake news. Often these outlets will present somewhat credible but distorted coverage of sell-side financial research, mixed with geopolitical news, while tolerating hate speech in their website commentary section”), Kocic was just a little more…. meandering. Consider the following “explanation” by the Deutsche Bank quant strategist for the reasons behind recent market instability:

At the core of current market developments lies cognitive instability — a cumulative erosion of traditional frames of reference, changes in interpretive frameworks and proliferation of intersecting narratives. There is too much new information, and not enough understanding. This “agitates” community and spontaneously creates the urgency for stabilization. There is an open contest for a narrative — not necessarily the most accurate, but one capable of providing the best fit — that would restore stability. The challenge is to construct from amorphous mass of unintelligible information, tendencies and speculations an acceptable narrative that restores the cognitive equilibrium.

Typically when normal run of things is interrupted, the following three signs define the discursive mode:

- Refusal to engage with the complexity of the situation,

- Emergence of conviction that there must be an “agent” (external or a disruptive force from within) responsible for the mess, and

- Refusal to know (ignoring or mistrusting the evidence).

In our view, all three factors are currently at play at reinforcing the existing market tensions.

And while Kocic’ argument tends to swing wildly from one extreme to another and everywhere inbetween as all self-respecting stream of consciousness writers, even those working in finance, tend to do, he does have a point in how the market rationalizes any diversion from the ordinary: a refusal to address the complexity, an attempt to create a fake narrative, and a refusal to know, all of which can be simply summarized as “denial” (with a dose of “bargaining” thrown in for good measure).

That said, the point of this post is not to criticize the communication style of Wall Street analysts (well maybe a little, we find it amusing that we have reached a point when financial strategists try to differentiate themselves by highlighting which post-modernist philosophical school they adhere to as evidenced by their writing), but to point out a relevant point from Kocic’s latest note (one which can be summarized simply by saying that the Fed continues to enable the drug-addicted patient, the market, with a constant supply of drugs, or as Kocic puts it, “a decade of stimulus and convexity supply has acted as a powerful “drug” whose withdrawal requires extraordinarily fine tuning, in the same way an abrupt withdrawal of substance can be damaging or even lethal for the addicted subject, while a slow withdrawal might be ineffective“) in which the DB strategist gives his response to the market’s emerging conviction that there must be an “agent” (external or a disruptive force from within) responsible for the current market mess, and also the market’s “Refusal to know” or merely ignoring/mistrusting the evidence.

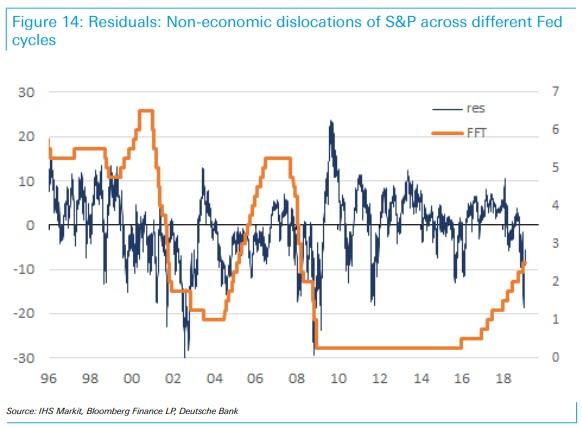

According to Kocic, the following chart serves to define the central point of the current market’s anxiety, a state he calls “hysterical recession”, and the underlying debate regarding its interpretation. It shows the history of S&P, used as a proxy for financial markets, overlaid with scaled PMI as a measure of economic health. “The two series show high degree of coordination with occasional outlier departures associated with times of financial troubles and recessions.”

As the DB strategist points out, “the mode of recent convergence and the market focus on the balance sheet unwind is very illuminating” and “shows that the Fed is still running a considerable “addiction liability.”

This is a problem because it confirms that 10 years after the crisis, monetary accommodation and central bank liquidity continue to be perceived as the main mechanism of economic growth and source of market stability (and instability, when the Fed threatens to remove them). Sure enough, financial markets staged a dramatic sell-off, and only when the Fed softened its rates path (in response to tighter financial conditions) did stability return.

To Kocic, “it would be difficult to construct a more convincing example of addiction than this. These shifting roles between the market and the Fed is not a new regime, but may simply be a return to the pre-crisis norm where the interplay was more two way.“

Furthermore, when stock prices are adjusted for a given economic regime (i.e. S&P regressed on PMI), extreme downward spikes of the corresponding residuals can be interpreted as indicators of recessionary markets (sharp drop in blue line on chart above). In the past, “residual outliers always showed up during the easing cycles”, according to Deutsche Bank, which adds that that while rate cuts start before residual spikes show up, “this does not mean that rate cuts are catalysts of recession” (needless to say, as we explained in detail several weeks ago when he showed why Powell is trapped, we completely disagree with this).

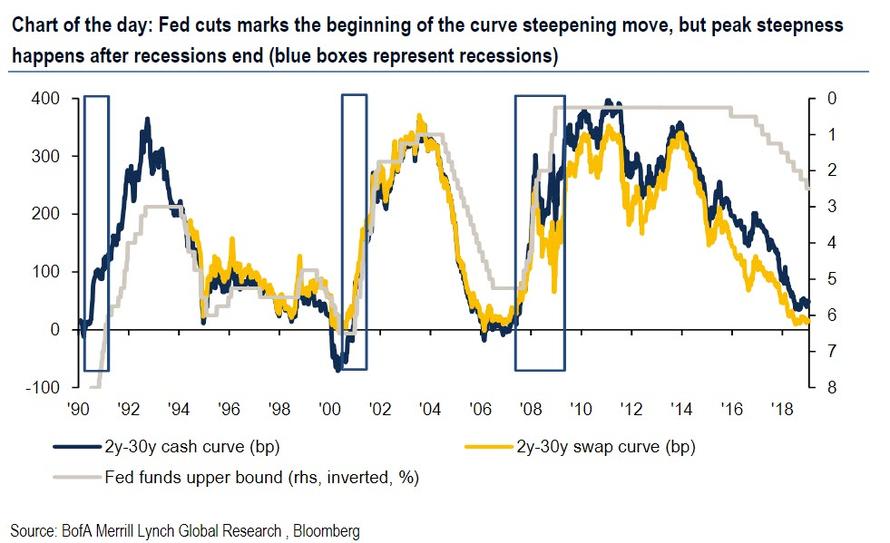

Rather, to Kocic, “the Fed begins to ease in anticipation of recession, in order to prepare the markets for economic slowdown and soften the shock ahead of time (if you expect cold weather along the way, you will bring warm cloths).” What we find surprising is that for a strategist who has defined his analysis for the past 3 years by analyzing the reflexivity between the market, the economy and the Fed, he is unable to grasp that by “trading itself into a recession”, the market is quite capable of creating the self-fulfilling prophecy in which mere expectations of a recession are realized once the Fed greenlights pre-recessionary trades. This also explains why, as BofA said on Friday, the most popular recession hedge right now is forward curve steepeners, as the market is convinced that the Fed did a “policy mistake”, and the next recession will begin over the next 12 months.

In any case, back to Kocic’s analysis, which finds that this time, the large negative residuals are showing up while the Fed is already tightening. To DB, this is notable as this departure from historical patterns is “behind the current perception of the Fed as a “disruptive force.” This is the central point of what Kocic has defined as the “ongoing confusion where the spike is misdiagnosed as a signal of recession and not for what it is – the restriking of the Fed put and a deliberate Fed’s effort to normalize the markets.” And, continuing along the same path of misguided logic, Fed tightening is misinterpreted as a policy mistake, or as Marko Kolanovic would call it, “fake news.”.

In conclusion, Kocic writes that while he disagrees with the recessionary interpretation of the current market configuration and perception of the Fed’s role in it, he does highlight the risk of reflexivity extending too far, and “shares concerns about the risks such interpretation can create, in the sense of it becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy, along the same lines as abrupt withdrawal of addictive substance can have fatal consequences for the patient.”

As a result, while Deutsche Bank believes that the risk of recession is being exaggerated by the market prices, it would “fade it cautiously”, especially if even more people start believing the recession narrative, and trade accordingly, in the reflexive process making a recession the new reality for both the market and the economy.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2RhIoOL Tyler Durden