Though millennials catch the most flack for taking out hundreds of thousands of dollars in student loans to pay for worthless college degrees that do little to improve their financial prospects in the “real world,” for older Americans who take out loans to finance their education later in life, the repercussions can be ten times worse.

Ante Grgas-Cice

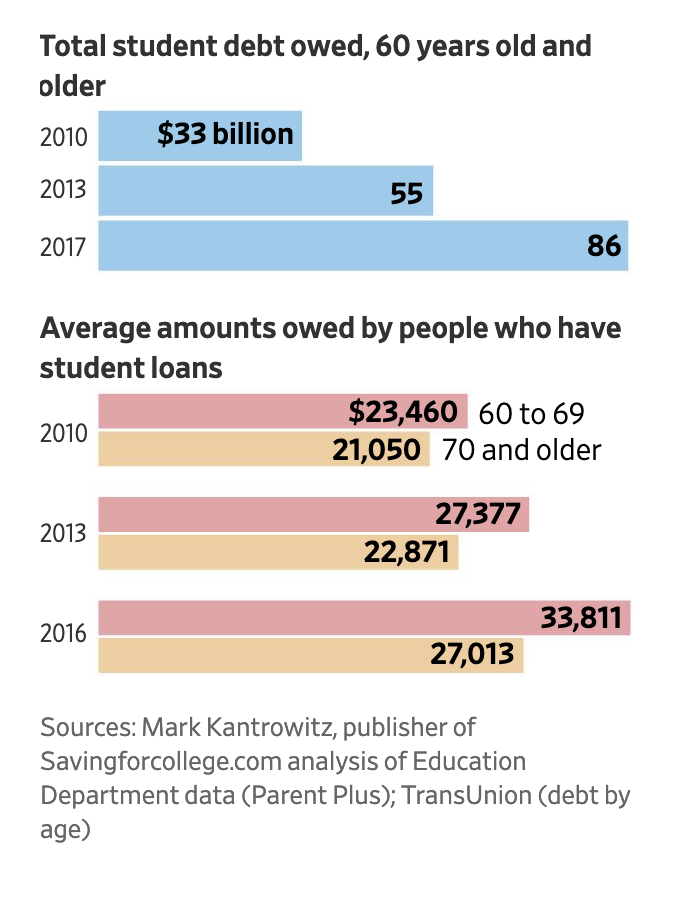

While it might not seem like much compared with the overall $1.4 trillion mountain of student loan debt rattling around the American economy, according to the Wall Street Journal, Americans over the age of 60 are struggling to pay down an aggregate $86 billion in student loan debt.

Student loan borrowers in their 60s, on average, owed $33,800 in 2017, up 44% from 2010, according to data compiled by credit-reporting firm TransUnion. Total student loan debt for people aged 60 and older rose 161% between 2010 and 2017, the biggest increase of any age group.

Rising student debt is the biggest contributor to the overall increase in the debt burden. for Americans aged 60 and older. US consumers who are 60 or older owed around $615 billion in credit cards, auto loans, personal loans and student loans as of 2017, up 84% since 2010, the largest increase of any age group.

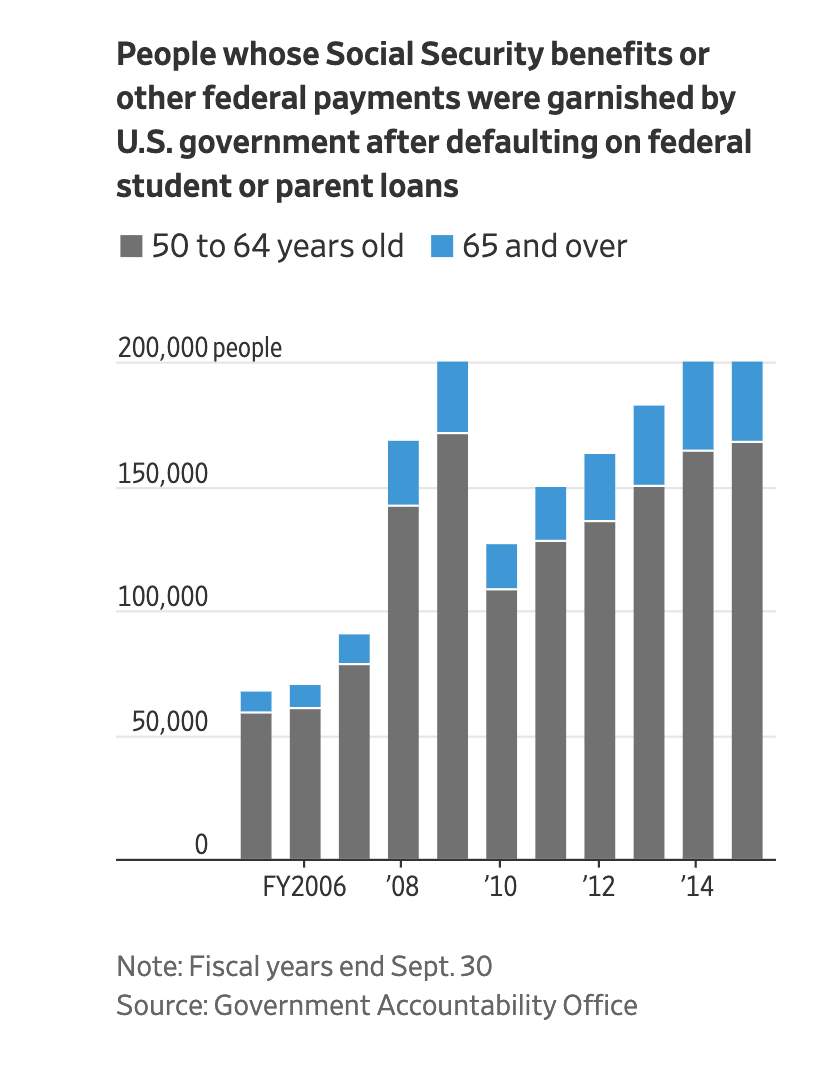

And for many, the results are nothing short of ruinous. Take Ante Grgas-Cice, 66. After a restaurant venture failed, he took out loans to go back to school, a decision he said “will haunt him for the rest of his life.” Because he has had difficulty paying down his $30,000 debt burden, the government garnished his social security check for a period last year.

At 66, Ante Grgas-Cice owes about $29,000 in student loans. His only income is a roughly $1,600 monthly Social Security check, which the federal government garnished for a period last year because he wasn’t paying his student loans.

Mr. Grgas-Cice said his decision to go back to school continues to haunt his life.

He signed up for student loans to attend the Art Institute of New York City in 2003 and 2004, after a restaurant venture failed. At the Art Institute, he studied culinary art and restaurant design and layout to upgrade his skills, he said. Subsequent restaurant ventures didn’t work and he’s currently unemployed.

To try and save money, Grgas-Cice traveled back to Croatia to live with his elderly mother for a period of time. He now relies on financial help from relatives to survive, and limits his food purchases to $7 a day.

“I put all my money to better myself,” Mr. Grgas-Cice said, adding that he was cautious in his spending. He says it’s painful to think about his current conditions.

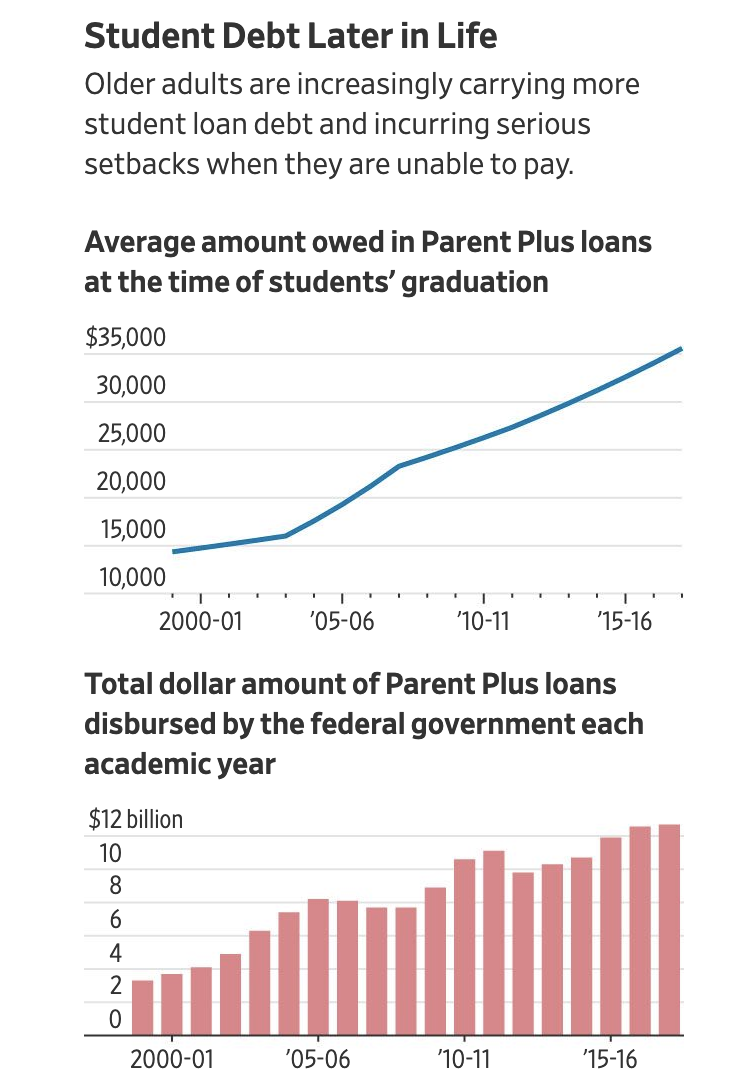

But most Americans who find themselves in this predicament took out loans on behalf of their children. In recent years, Sallie Mae and Citizens Financial Group have been marketing “Parent Plus” loans to concerned parents who want to help out with their children’s college education, but who don’t have the money to pay outright. The upshot of these loans is that parents often get stuck with a tab they can’t afford.

An interesting loophole has contributed to this situation. The federal government caps the amount that undergraduate students can borrow, but there’s no limit on the money that can be borrowed by their parents.

Hence, the “Parent Plus” loan, one of the most economically harmful consumer debt products of its time.

The federal government disbursed $12.7 billion in new “Parent Plus” loans during the 2017-18 academic year, up from $7.7 billion a decade prior and $3.3 billion in 1999-2000, according to an analysis of Education Department data by Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of Savingforcollege.com.

Its underwriting standards are generally looser than banks and other private lenders, making it easier for more applicants to qualify. Parents on average owed an estimated $35,600 in these loans at the time of their children’s college graduation last spring, according to Mr. Kantrowitz. They owed nearly $6,400 on average (not adjusted for inflation) in the spring of 1993.

One parent who falls into this category is Christopher Raymond of North Danville, Vt., who was a high-school history teacher for 32 years.

One parent who spoke with WSJ described how “Parent Plus” upended their retirement after he signed up for $136,000 in loans to pay for the education of his two children.

Each month, he and his ex-wife pay a combined $1,900. They believe they will be stuck paying off these loans into their 70s. “It’s a very dark cloud that’s always in the back of my mind,” he said.

Another parent described how payments toward his Parent Plus loans led him to rack up $40,000 in credit card debt. Living with this debt isn’t only financially ruinous, he said. It impacts his ability to live a health life.

Raymond Abdullah, 65 years old, has around $40,000 of credit-card debt and a balance of about $11,000 on a federal Plus loan he signed up for to pay for his son’s tuition about 22 years ago.

The credit card debt grew over the past decade after he retired from work as a jeweler. He finds himself turning to cards more often to pay for everyday expenses including gas and groceries. He says he needs to keep cash on hand to pay for other expenses, including the $400 monthly payment towards the college loan.

The debt, he says, “affects your blood pressure, it affects your overall well-being,” he said. “At this age you don’t expect to be in debt. It’s not where you want to be.”

For some, relief can be found through various federal programs that can halt the garnishing of wages or social security checks. But while most millennials with loans can at least hope that one day they will eventually conquer this burden, older Americans must live with the knowledge that the dark cloud of their debt will follow them for the rest of their natural lives.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2SjXKXJ Tyler Durden