Submitted by Peter Verleger of OilPrice.com

In the late sixties, an economic debate began between East Coast economics departments (saltwater universities) and midwestern colleges (freshwater universities). Milton Friedman, the spokesperson for the freshwater universities, made the claim that “money mattered.” Others in the Midwest took this perspective and ran with it to the point where they asserted that “only money mattered.”

Friedman made his point to take on the Keynesians at the saltwater institutions, who for decades had argued it was deficit spending that determined economic activity. Monetary issues tended to be ignored in the standard Keynesian model. If asked, proponents would assert that “liquidity” traps essentially made monetary actions useless.

The debate was eventually resolved, at least partially, when Friedman, Paul Samuelson, and Robert Solow (all Nobel laureates) discussed the issue at MIT and several other locations. Their conclusion at the time was that “money matters.” This did not mean that deficit spending did not matter, as the Republican Congress that just ended has clearly demonstrated. However, monetary policy is important.

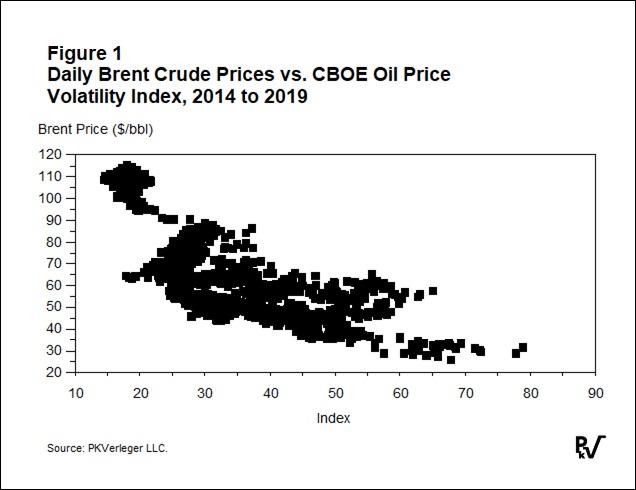

In the same way, oil price volatility matters. To drive the point home, see Figure 1, which compares daily Brent prices to the CBOE’s oil price volatility index. The graph presents 1,274 observations. One does not need a computer, a statistics degree, or a Ph.D. in econometrics to understand that low values of volatility are associated with high prices and high values with low prices.

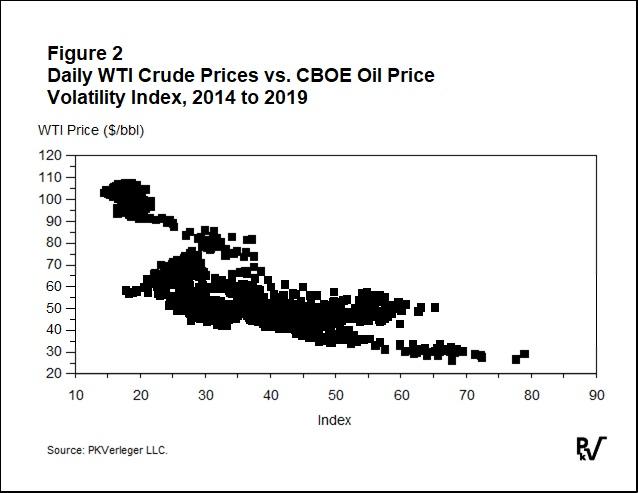

Figure 2 shows the relationship between WTI prices and the same volatility index. Again, the results are clear. High prices are associated with low price volatility and low prices with high volatility. Volatility alone explains forty percent of the day-to-day variation in WTI prices from 2014 to 2019 in a model where adjustments are made to remove autocorrelation.

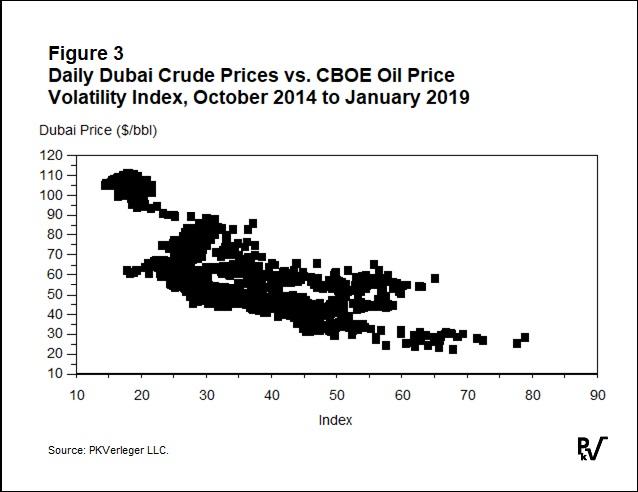

The same results are obtained for Dubai crude, even though it is delivered halfway around the world. The long arm of US markets reaches the Persian Gulf. As can be seen from Figure 3, the relationship is essentially identical to those for Brent and WTI. CBOE volatility explains forty percent of the variance in Dubai crude prices, just as it explains the movement of Brent and WTI prices.

These data make it clear that oil-exporting countries seeking higher prices need to reduce volatility. Simply meeting and talking about production cuts no longer seems to be enough. Perhaps investors or speculators hearing the talk no longer believe anything will be done. It is even possible that some participants hear the talk and sell futures or buy puts, betting against OPEC or OPEC+. Their actions boost volatility and drive prices down.

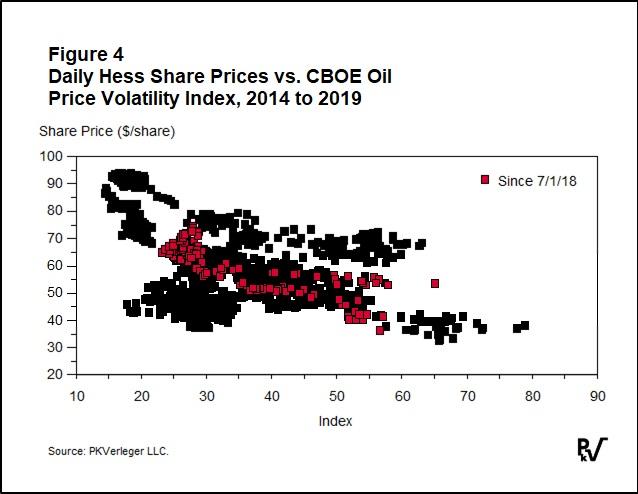

The independent oil producers developing U.S. shale production, as well as participating in offshore developments such as in Guyana, are also affected by price volatility. Take, for example, the impact of price volatility on the share price of Hess, an independent producer, that I show in Figure 4.

In a statistical test in which I regressed the day-to-day change in share price, I found that, since July 1, 2018, changes in volatility explain ninety-seven percent of the variance in the Hess share price. The managers at Hess clearly need to suppress price volatility to boost their share value.

John Hess, Hess’ CEO, has not yet recognized the importance of volatility. (Perhaps he will read of my observation in some report.) Instead, he believes the oil industry needs to hire publicists, as he explained at the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland:

“How do you get the hearts and minds of investors back? That is a real challenge for our industry,” said John Hess, the founder of independent U.S. producer Hess Corp.

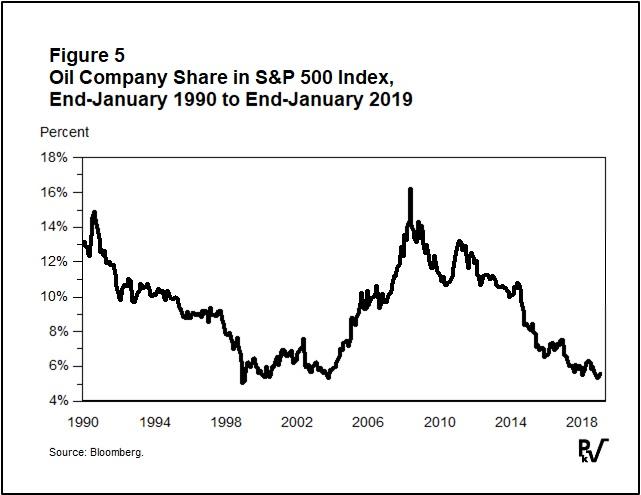

He said investor frustration with the oil industry was manifested by the fact that the share of energy companies in the S&P index had shrunk to 5.5 percent from 16 percent 10 years ago.

“We will have to compete against other industries in the S&P to create the value proposition that makes us more attractive. A new paradigm is coming up which is to generate free cash and share some of this cash with investors,” he said.

Hess later added that “we [oil firms] need to engage with policymakers and the public to understand the huge task we have ahead.” He and other executives from major oil companies pointed to the billions they believe must be invested in exploration and production.

I note first that the Hess share price has declined twenty-one percent from its peak in August 2014. In part, the decline can be explained by the last line of Mr. Hess’ statement, that is, the company has shared some of its free cash with investors. The company’s dividend yield has been put at 1.75 percent. This would be significantly higher if the firm shared more cash with investors and drilled less. ExxonMobil shares yield 4.3 percent, for example, while the dividend yield on Chevron is four percent.

The simple fact is that Hess seems not to be offering investors an attractive reward. However, the firm’s problems go beyond cash-flow generation. At Davos, Hess, executives from other major oil companies, and OPEC secretary-general Mohammed Barkindo all bemoaned the industry’s inability to attract investors. As Figure 5 illustrates, the share of oil companies in the S&P 500 has declined steadily from the sixteen-percent peak achieved in 2008. Investors are just not attracted to oil.

I doubt many readers believe that Hess, the oil industry as a group, or even the oil industry acting in cooperation with OPEC can change investor views through a public relations campaign. Such efforts are almost always counterproductive unless accompanied by other actions.

There is also little likelihood that policymakers will be convinced to do much “to address the huge task [oil firms have] ahead.” Oil producers and the oil industry are on their own.

There is something, though, that oil-producing countries or even states such as Texas and provinces such as Alberta could do to address the investor issue. Even companies acting alone to avoid violating antitrust statutes could help. All they need do is take steps to lower price volatility.

Let me repeat that statement. Oil producers, oil states, and oil provinces with an interest in higher oil prices can reach this goal by lowering oil price volatility, which they can achieve by intervening in the market to slow price declines or increases.

Over the last forty-five years, oil ministers from OPEC, and now other producers who have joined their efforts to manage the market, have operated on the belief that they can move the market by issuing statements on production and export decisions after their sporadic meetings. For example, in November 2018, Saudi oil minister Khalid al Falih said, “We need to do whatever it takes to balance the oil market” in a talk he gave a month before an OPEC meeting. The minister likely expected markets to respond positively the day after this pronouncement. In this case, though, prices were down another seven percent within a week.

The story would have been very different had Minister al-Falih or other Saudi officials stepped in and purchased oil. Saudi Arabia could have bought back a cargo scheduled to load if the original buyer agreed. Alternatively, Saudi Arabia could have acquired oil on the Dubai spot market. For that matter, Saudi Arabia could have purchased a cargo of Brent or WTI. All that was needed was an action that took oil off the market.

An easier, quicker tactic would be to buy oil in the futures markets. Indeed, a government purchase of a relatively small number of futures would have stopped the price decline cold. The action would be equivalent to buying physical oil but could occur instantaneously. The price decrease would have been arrested rapidly if these purchases were followed by an agreement to cut supply.

Today, those interested in stabilizing prices—such as ministers from oil-exporting nations—need to recognize their words have little or no impact unless they are accompanied by immediate actions such as canceling shipments or selling physical oil from stockpiles. Oil markets, particularly futures markets, have grown to a point where traders can add or subtract the equivalent of one day’s global consumption, one hundred million barrels, to or from supply in a minute. Furthermore, these volumes are backed by cash held at the world’s major financial institutions.

In less than one month, representatives from the world oil industry will reconvene at the annual CERAWeek conference in Houston. The topic raised by John Hess in Davos will likely be one of the most important subjects discussed. If the executives gathered in Houston actually want to see higher prices, though, they would focus on a price-stabilization program. The futures markets should be seen as a tool that could help them reach their goal.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2GBHwn8 Tyler Durden