In one of the world’s most developed economies, soaring costs for housing and education are rapidly widening the wealth-distribution gap between the younger and older generations amid the backdrop of one of the longest economic expansions in the country’s history. As younger workers grapple with the notion that they may never be able to afford a home, a backlash is stirring in the political arena, as younger voters embrace progressive (some would say “socialist”) politicians.

No, we’re not talking about the US. We’re talking about Australia.

After six years of tumultuous Liberal rule, the Labour Party is hoping to wrest back control of the government during elections later this year. And it sees tackling this intergenerational divide as the best way to do it. And combating the country’s increasingly unaffordable housing bubble is a key plank of its proposals. The party has pledged to curb tax breaks for property investors that helped drive up home prices (alongside an influx of foreign capital).

Labor leader Bill Shorten has promised to scrap tax refunds worth A$5 billion ($3.6 billion) a year for share investors. The benefits are already being seen in the polls, where Labour is seeing a slight advantage.

After 27 years of uninterrupted economic growth, Australians are struggling with the fact that the wealthy have enjoyed the bulk of the economic benefits.

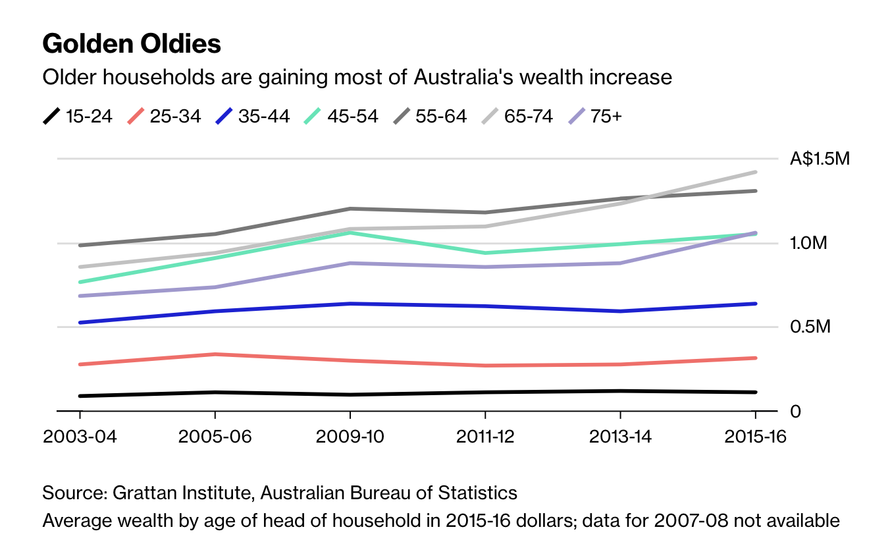

While Australia has avoided recession for 27 years, the spoils have not been shared evenly as older people capture a greater share of the nation’s wealth. According to the Grattan Institute, households headed by people aged 65-74 were on average A$566,000 wealthier in 2015-16 than the same age group was 12 years earlier. That far outstrips growth in other bands and compares with just A$38,000 for the 25-34 age group.

And economists are worried that such an extreme concentration of wealth among older Australians…

…could hurt the country’s economy.

Such a concentration of wealth among older Australians can hurt the real economy, according to Danielle Wood, an economist at the Melbourne-based think tank. Younger Australians priced out of the property market, for instance, are forced to live further from cities – lengthening their commutes and reducing the likelihood of second income-earners working full time, she said in an interview with Bloomberg Television Thursday.

“Housing affordability has clearly been the No. 1 economic issue for younger Australians in the past decade,” Wood said.

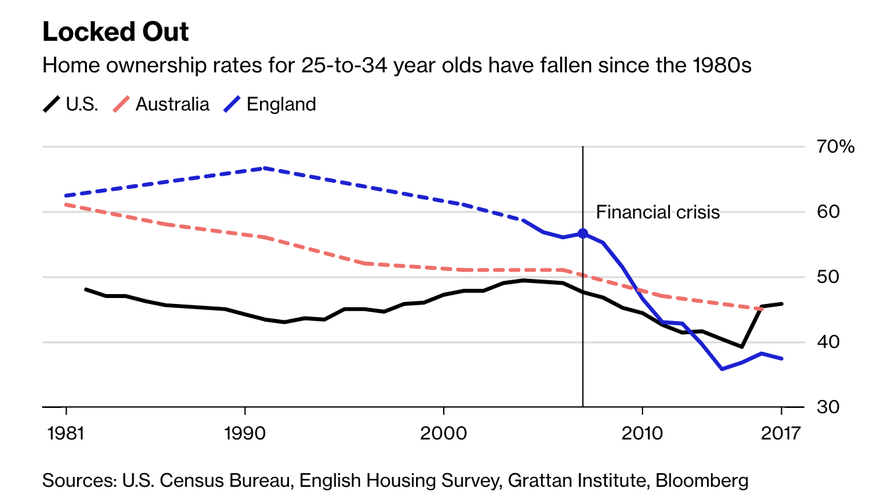

And as home prices have soared, home ownership rates among younger Australians have plummeted.

To try and combat this, Shorten proposed that a tax break known as negative gearing which allows homeowners to treat costs associated with owning a rental home as a tax deduction (though, to be fair, that certainly sounds like it could have some unintended consequences for the property market). He has also promised to subsidize rents and build homes.

Though as the bubble in the country’s hottest housing markets deflates from a mid-2017 peak, the risk of sparking a destabilizing crash are also probably worth considering.

While Sydney’s median house price is still more than A$900,000, and the city remains the world’s third least-affordable housing market where only 45% of residents aged 25-34 own their own home (down 16% points from the 1980), prices have already fallen 12% since their mid-2017 peak.

To be sure, this is just one market. But with China clamping down on capital outflows, the risks of a domino effect are certainly worth considering.

But we’re sure that, if Australia’s progressives do prevail during the May election and the housing bubble does collapse, they won’t make the same mistake the US did and choose to bail out the people who paid for these overpriced homes, and not the banks that enabled them.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2IpxF5E Tyler Durden