Did you know legendary American consulting firm McKinsey ran an in-house hedge fund? Apparently, neither did many of the firm’s clients.

According to a report in the New York Times, the fund has recently attracted a series of lawsuits and scrutiny from the DOJ and Congress over its failure to disclose conflicts of interest between investments held by its $4 billion in-house fund, McKinsey Investment Office, and its clients.

McKinsey launched the fund in the 1990s in the midst of a brutal war for talent with Wall Street firms. The fund was intended to incentivize high performing employees to stay with the firm. But though the firm defended its refusal to disclose these conflicts by claiming there maintains that there’s is a wall between the two businesses, lawmakers, judges and others are beginning to question whether or not this is true, particularly after it was revealed that senior employees in McKinsey’s consulting business sit on the fund’s board.

Virginia bankruptcy court where a judge reopened a case involving a coal company after discovering the MIO was one of the bankrupt firm’s secured creditors.

After the NYT published its report, the DOJ announced that it had reached a settlement with McKinsey over cases involving its disclosure of conflicts in bankruptcy advisory cases. As part of the settlement, McKinsey agreed to pay out $15 million to creditors it represented in these bankruptcy cases, and stated that if McKinsey doesn’t remedy its disclosure practices, DOJ could seek further penalties.

Former employees of MIO confirmed to the Times that one reason the in-house hedge fund has been so secretive is that McKinsey doesn’t want anybody “connecting the dots” between its investments and its clients. Instead of housing its money at its headquarters in NYC, McKinsey stashes its $4 billion on the English Channel island of Guernsey.

Here are a few other highlights from the sprawling NYT report:

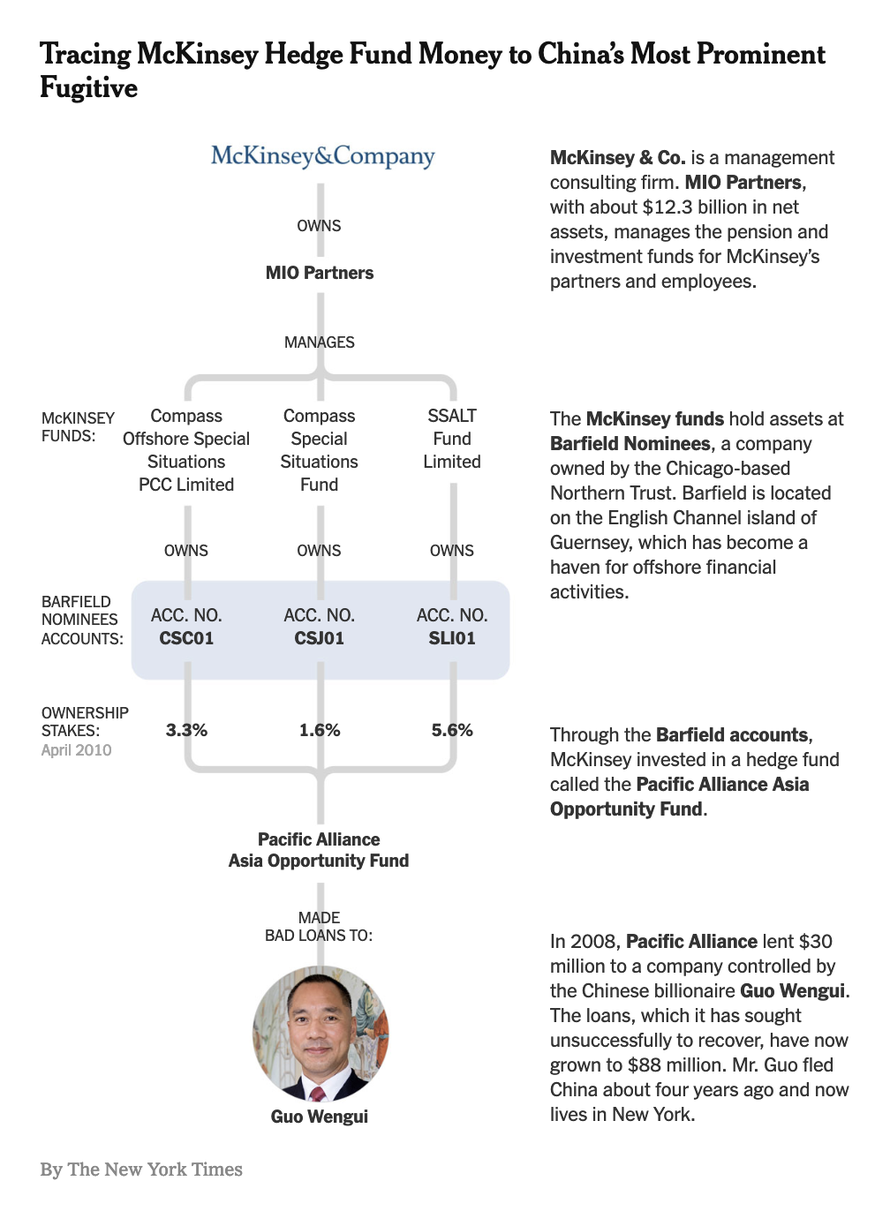

A fund in which MIO has invested is a creditor to China’s highest-profile fugitive.

The McKinsey fund took stakes in two China-focused PAG funds. In a 2010 London exchange filing, PAG disclosed that MIO had a stake of more than 10 percent in one fund, worth about $20 million. At the end of 2015, MIO also owned more than a quarter of another China-focused PAG fund.

In 2008, Pacific Alliance had made a big bet on a real estate mogul who owned a colossal office and luxury apartment complex next to the site of that year’s Summer Olympics in Beijing. Court records show that it lent $30 million to a company controlled by the mogul, who had deep ties to China’s intelligence community and was already notorious for allegedly orchestrating the downfall of a Beijing vice mayor with a sex tape.

PAG says it was never repaid its loan. The mogul has fled China for New York. In China, he faces corruption and rape charges, which he says are false. PAG sued him in a New York court in 2017, saying he owed it about $88 million, court records show.

His name is Guo Wengui, though he also goes by Miles Kwok. He is China’s highest-profile fugitive, and for years McKinsey was, through PAG, one of his creditors, a fact hidden through Barfield Nominees. There is no evidence that McKinsey knew its investment would find its way to Mr. Guo, with whom the firm said it had no direct dealings.

The NYT even produced an infographic to illustrate the connections between McKinsey’s money and the fugitive in question, who is wanted on rape and corruption charges.

One advocate from a nonprofit that seeks to bring more scrutiny to tax havens pointed out that McKinsey’s use of tax havens for its investments contradicts its consulting business’s espousing of corporate best practices.

But John Christensen, a founder of the Tax Justice Network, a group based in Britain that seeks to bring more transparency to tax havens, said there was a disconnect between McKinsey’s mission of spreading corporate best practices and its use of tax havens like Guernsey.

“I can’t think of any legitimate, genuinely economic reason for using a place like that,” Mr. Christensen said. He should know: For 11 years, Mr. Christensen was the economic adviser to Jersey, a neighboring tax haven.

The longtime manager of MIO, Todd Tibbetts, is a virtual ghost. The NYT’s investigation turned up almost nothing on the money manager, despite his track record of reporting multiple decades of market-beating returns. Tibbetts enforces a code of silence among his managers that is so intense, they are even prohibited from attending industry events for fear of interacting with other market participants.

In its statement, McKinsey said, “We continue to stand by our disclosures, which have always fully complied with the law, and we are confident that Alix’s fraud claims will be exposed as completely meritless.”

Until the flurry of attention from the bankruptcies and the Puerto Rico controversy, the very existence of McKinsey’s hedge fund had largely escaped public notice. McKinsey declined to make Todd Tibbetts, the fund’s longtime chief investment officer, or any other officials available for interviews for this article.

For someone who manages such a large and successful portfolio, there is surprisingly little public information about Mr. Tibbetts. So secretive is the fund under Mr. Tibbetts that its managers were discouraged from attending industry events and, even when they did, from talking to participants, one former fund executive said.

McKinsey’s in-house fund was invested in Puerto Rico bonds while also advising the government of Puerto Rico during the restructuring, presenting what Elizabeth Warren described as a clear conflict of interest.

In Puerto Rico, where McKinsey is advising a board that seeks to reduce the island’s crippling debt, The New York Times reported last year that the hedge fund was invested in bonds that gave it a stake in the outcome. Afterward, a bipartisan group of House members introduced a bill to compel advisers like McKinsey to disclose potential conflicts of interest.

And Representative Nydia M. Velázquez, a New York Democrat, and Senator Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts Democrat now running for president, wrote to McKinsey, assailing its conflict-of-interest disclosure as “opaque or nonexistent.” McKinsey responded that there was no relationship between its work in Puerto Rico and the fund’s bond investments.

While McKinsey was advising Valeant Pharmaceuticals – a company that was at one time run by a former McKinsey partner – it held a stake in the “pharmaceutical Enron” indirectly through outside hedge funds, meaning that these funds were potentially trading in the company while McKinsey was giving Valeant advice about which drugmakers to buy.

As McKinsey consultants were advising Valeant in late 2014, two of MIO’s funds, Compass TPM and Compass Offshore TPM, acquired an indirect stake in Valeant, through Visium Asset Management, a fund soon to implode in an insider-trading scandal.

Through another outside hedge fund, Aristeia Capital, two other MIO funds acquired shares in Valeant in early 2015, after the company agreed to buy Dendreon, a bankrupt drugmaker. The McKinsey funds were listed among the eight noteholders of Dendreon, entitled to a portion of the $495 million, in cash and Valeant shares, that Valeant paid for the company.

In a statement, Aristeia said it had learned of McKinsey’s role advising Valeant only when contacted by The Times. “Aristeia never sought input from MIO on potential conflicts, because MIO had no investment discretion in respect to these assets,” the company said.

McKinsey, in its statement, said its hedge fund “had no input into the investment decisions made by Visium and Aristeia,” its third-party managers. Valeant, now called Bausch Health, said it hadn’t been advised by McKinsey on mergers and acquisitions since May 2016.

MIO’s flagship fund has posted market beating returns more often than not. Between 2000 and 2010, the fund posted an average return above 9%, compared with roughly 1.6% loss for the S&P 500. And while McKinsey prefers to hide behind this wall of separation between the fund and its consulting business, experts told the NYT that it’s impossible to completely rule out the possibility of a conflict.

“The mistake people make is to say, ‘Well, conflicts of interest aren’t so dangerous, because well-meaning professionals can navigate them objectively,'” said Daylian Cain, who teaches business ethics at the Yale School of Management. “But the research is out on this: No, they can’t.”

Particularly not when the leader of the firm’s bankruptcy practice also holds a seat on the hedge-fund’s board.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2E4tarH Tyler Durden