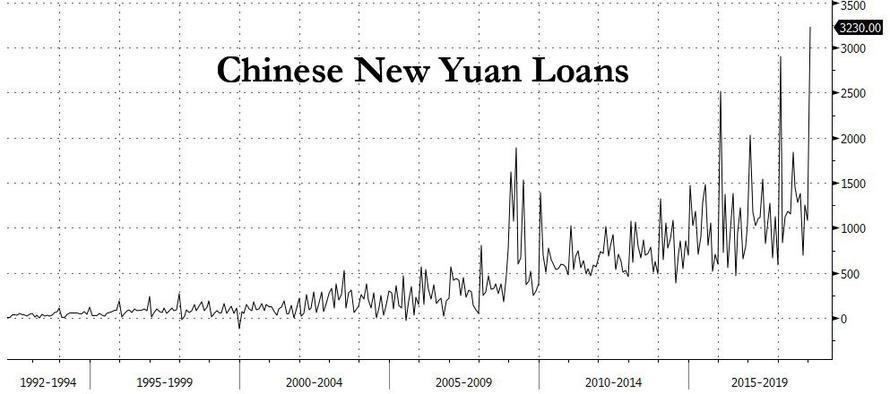

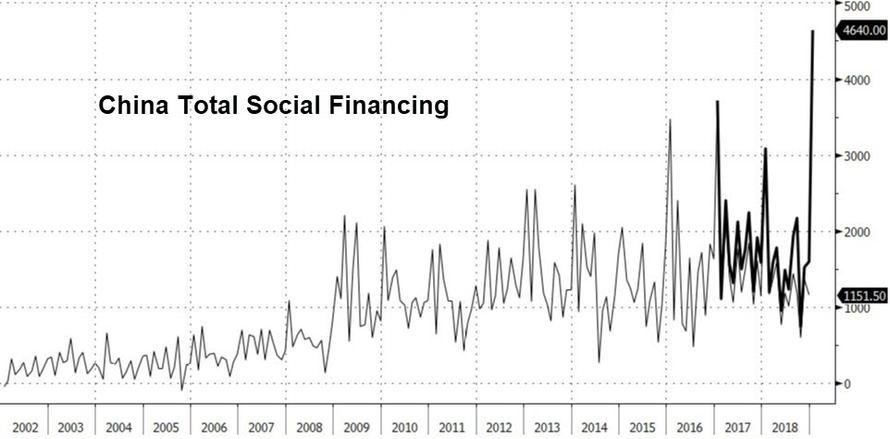

Months before Beijing abandoned its deleveraging plans and approved a gargantuan 4.64 trillion yuan credit injection (including the “shadow” credit that the government had vowed to curb) – which, as we pointed out at the time, resembled the January 2016 “Shanghai Accord” intervention (when Beijing famously intervened to stop global stock markets from careening off a cliff) – a team of S&P credit analysts warned in an October report that China’s debt burden might be much larger than previously believed.

Against a backdrop of soaring corporate defaults, the team from S&P warned that investors could safely tack on another ~40% of debt/GDP to China’s total (with even more likely hidden from view) after a careful analysis of a new source of shadow debt being tapped by local governments to further their development plans. These Local Government Financing Vehicles, or LGFVs, represented “an iceberg with titanic credit risks” as local officials had increasingly turned to these sources of shadow financing to finance development projects while bureaucrats in Beijing struggled to turn off the credit taps.

Now that Beijing has reckoned with the idea that now is not the time to try and contain the country’s massive debt load, even as the percentage of bad debt balloons, it increasingly appears that these measures might be too little, too late for investors who financed these LGFVs, as the Wall Street Journal revealed in a report about how a local government in China’s impoverished Southern had caused a stir by stiffing its creditors after racking up a debt pile – largely through these LGFVs – equivalent to roughly three times the government’s annual revenue.

When a group of wealthy investors traveled to Sanhe to confront the local government, they were swiftly rebuffed, leaving them little recourse to recover their money.

Meanwhile, many of the buildings that their money helped to finance stood half-finished.

A building splurge in this impoverished pocket of rural China ended in half-finished projects and a trail of angry investors from some of the country’s wealthiest areas.

On a recent winter workday, investors and representatives from private fund companies in Shanghai and elsewhere descended on Sandu, a county in the deep south where tens of thousands of locals live on less than a dollar a day. After taxi rides from the high-speed rail station that took them past incomplete buildings and a gigantic golden statue of a man on horseback, they sat in government offices, demanding repayment.

“We sympathize with you investors,” Jian Shiwei, deputy general manager of a Sandu government-backed investment company that borrowed hundreds of millions of yuan to develop the area. “But there’s no money right now.”

Though it might be tempting to chalk this up to the mismanagement of Sanhe’s local officials, WSJ claimed that situations like this are playing out in rural areas across China.

The standoff in Sandu is a microcosm of China’s mounting debt problem. Across the country, local governments and their more than 2,000 financing companies have run up trillions of dollars of debt to borrow and build their way to prosperity, tapping into ready financing from well-off investors chasing higher returns. Now the bills are coming due, and China’s slowing economy, curbs by Beijing on risky financing—and the massive scale of borrowing—are plaguing repayment and leaving some investors in limbo.

After the confrontation with investors and just before this month’s Lunar New Year holiday, Sandu hustled out interest payments for some overdue obligations. Still, investors and brokers estimate that the government and its companies will need to deliver two billion yuan ($297.6 million) more in payments this year, nearly three times Sandu’s annual revenue.

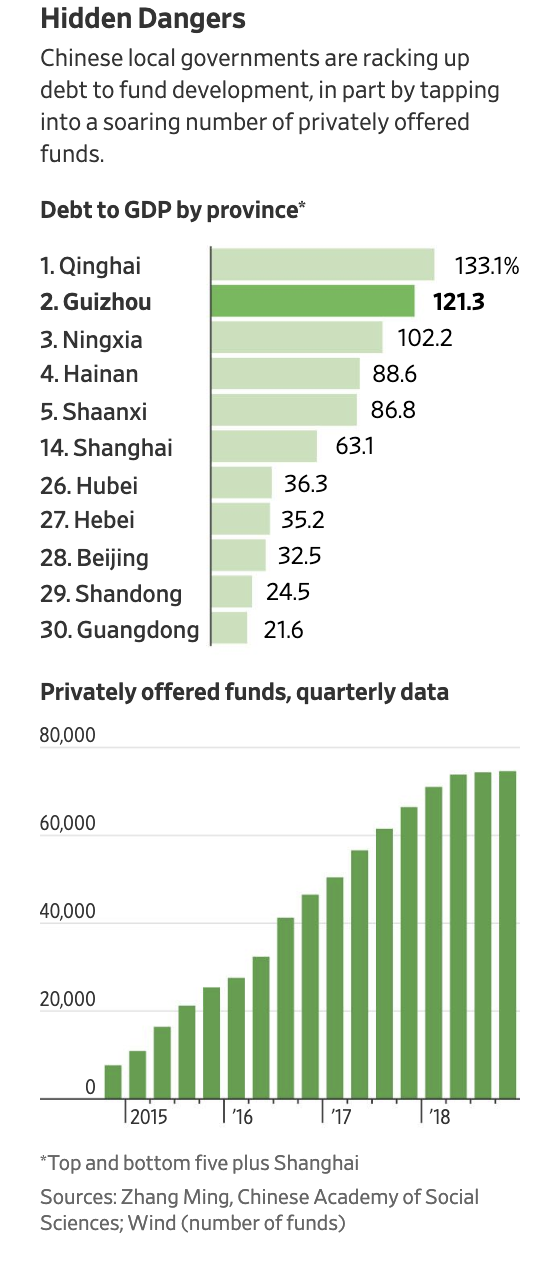

Many regional governments are already struggling with debt piles in excess of 100% debt-to-GDP, and that’s before factoring in the shadow financing sources.

And it’s not just wealthy Chinese fund managers who are being left in the lurch; many residents opted to invest in these vehicles after being seduced with high advertised returns – only to see their savings vanish. One investor who spoke with WSJ claimed that the shortfall wasn’t the local government’s fault, but a result of mismanagement and regulatory failures impacting the entire Chinese financial system.

“Sandu has its problems, but we can’t blame it,” said Jiang Xiaqiu, a factory owner and investor who bought 1.6 million yuan of Sandu’s debt via a private fund in Beijing, with an advertised 9% annual return. “It’s the whole financial system and how poorly regulated the private fund industry has been.”

Sandu’s government debt totaled 3.73 billion yuan in 2017, according to official figures. Deputy propaganda chief Wu Maohua declined to comment on what the sum includes; some economists, analysts and experts say it doesn’t cover recent borrowings by government-backed investment companies, including off-the-book borrowing from private funds.

In Sanhe, problems first arose after the local Communist Party chief was removed in a bribery investigation last year. The region missed its first debt payment in September, but has been struggling to make up these payments.

Mr. Wu said the county is working to resolve its debts, pointing to the overdue payments given to some investors. “You can see the government is being very diligent,” he said.

For its borrowing spree, Sandu turned to funds like the one Ms. Jiang invested in. These privately offered funds have mushroomed, with more than 74,000 of them, nearly 10 times the number five years ago. Independent brokers and wealth advisers market the funds to well-off clients. Ms. Jiang said a broker connected her with fund managers.

While putting a number on thee amount of shadow debt in the system is difficult due to the opacity of the Chinese financial system, one economist at a domestic think tank estimated that off-balance-sheet borrowings by local governments could be as much as 23.6 trillion yuan, as of the end of 2017, meaning that total is likely higher today, as governments have been forced to tap these vehicles during Beijing’s deleveraging campaign.

The proliferation of private funds and other money-raising channels for local governments makes it difficult for economists and for Beijing to track the total amount of borrowings. Official figures pegged the sum of local and central government debt at 29.95 trillion yuan ($4.457 trillion) in 2017, roughly 36% of the economy.

[…]

Off-balance-sheet borrowings by local governments are estimated to be nearly just as much, at 23.6 trillion yuan by 2017, according to Zhang Ming, an economist at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a government think tank. When this hidden debt is factored in, he said, total government debt is about 67% of the economy. But the proportion is much higher in some places, such as less-developed areas trying to catch up, and Mr. Zhang’s estimates don’t capture all borrowings, especially those involving private funds outside banking channels.

Fortunately, Beijing’s latest reversal should at least reopen the taps for on-the-books debt, allowing governments to restart some of these projects, and potentially raise money to pay back the LGFVs. But whether this could work as a long-term solution is doubtful, as most see it as just another episode of can-kicking by Beijing, in the absence of real structural reforms.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2IK0PwJ Tyler Durden