Authored by Alexander Mercouris via ConsortiumNews.com,

A British elite challenged by large parts of the British population is rallying around trumped-up fear of Russia as a means of protecting its interests…

Hostility to Russia is one of the most enduring, as well as one of the most destructive, realities of British life. Its persistence is illustrated by one of the most interesting but least reported facts about the Skripal affair.

This is that Sergey Skripal, the Russian former GRU operative who was the main target of the recent Salisbury poisoning attack, was recruited by British intelligence and became a British spy in 1995, four years after the USSR collapsed, at a time when the Cold War was formally over.

In 1995 Boris Yeltsin was President of Russia, Communism was supposedly defeated, the once mighty Soviet military was no more, and a succession of pro-Western governments in Russia were attempting unsuccessfully to carry out IMF proposed ‘reforms’. In a sign of the new found friendship which supposedly existed between Britain and Russia the British Queen toured Moscow and St. Petersburg the year before.

Yet notwithstanding all the appearances of friendship, and despite the fact that Russia in 1995 posed no conceivable threat to Britain, it turns out that British intelligence was still up to its old game of recruiting Russian spies to spy on Russia.

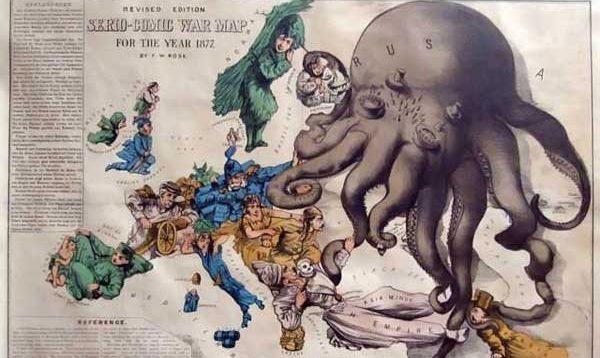

Britain’s Long History of Russophobia

This has in fact been the constant pattern of Anglo-Russian relations ever since the Napoleonic Wars.

Brief periods of seeming friendship – often brought about by a challenge posed by a common enemy – alternating with much longer periods of often intense hostility.

This hostility – at least from the British side – is not easy to understand.

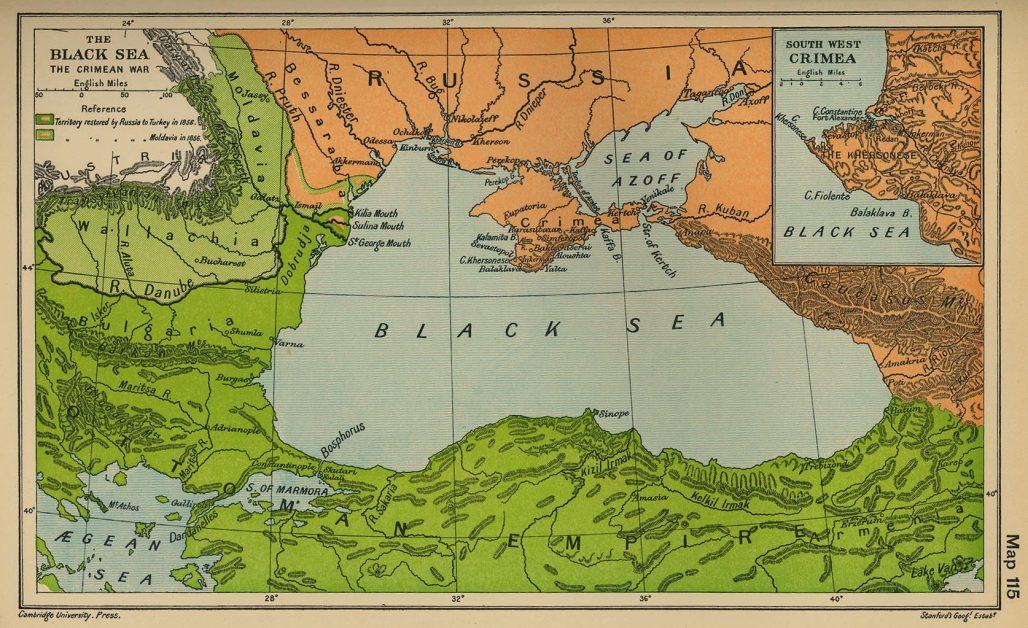

Russia has never invaded or directly threatened Britain. On the only two occasions when Britain and Russia have fought each other – during the Crimean War of 1854 to 1856, and during the Russian Civil War of 1918 to 1921 – the fighting has all taken place on Russian territory, and has been initiated by Britain.

Nonetheless, despite its lack of any obvious cause, British hostility to Russia is a constant and enduring fact of British political and cultural life. The best that can be said about it is that it appears to be a predominantly elite phenomenon.

British Russophobia Peaks

If British hostility to Russia is a constant, it is nonetheless true that save possibly for the period immediately preceding the Crimean War, it has never been as intense as it is today.

Moreover, not only has it reached levels of intensity scarcely seen before, but it is becoming central to Britain’s politics in ways which are now doing serious harm.

This harm is both domestic, in that it is corrupting British politics, and international, in that it is not only marginalising Britain internationally but is also poisoning the international atmosphere.

Why is this so?

Elite British Consensus

For Britain’s elite, riven apart by Brexit and increasingly unsure of the hold it has over the loyalty of the British population, hostility to Russia has become the one issue it can unite around. As a result hostility to Russia is now serving an essential integrating role within Britain’s elite, binding it together at a time when tensions over Brexit risk tearing it apart.

To get a sense of this consider two articles that have both appeared recently in the British media, one in the staunchly anti-Brexit Guardian, the other in the equally staunchly pro-Brexit Daily Telegraph.

The article in the Guardian, by Will Hutton and Andrew Adonis, is intended to refute a narrative of British distinctiveness supposedly invented by the pro-Brexit camp. As such the article claims (rightly) that Britain has historically always been closely integrated with Europe.

However when developing this argument the article engages in some remarkable historical misrepresentation of its own. Not surprisingly, Russia is the subject. Just consider for example this paragraph:

“…..note for devotees of Darkest Hour and Dunkirk: Britain was never “alone” and could not have triumphed [in the Second World War against Hitler] had it been so. Even in its darkest hour Britain could call on its then vast empire and, within 18 months, on the Americans, too.”

Russia’s indispensable contribution to the defeat of Hitler is deleted from the whole narrative. The U.S., which became involved in the war against Hitler in December 1941, is mentioned. Russia, which became involved in the war against Hitler in June 1941, i.e. before the U.S., and whose contribution to the defeat of Hitler was much greater, is not.

Whilst claiming to refute pro-Brexit myths about the Second World War the article creates myths of its own, turning the fact that Russia was an ally of Britain in that war into a non-fact.

The article does however have quite a lot to say about Russia:

“Putin’s Russia is behaving like the fascist regimes of the 1930s, backed by sophisticated raids from online troll factories. Citizens – and ominously younger voters in some European countries – are more and more willing to tolerate the subversion of democratic norms and express support for authoritarian alternatives.

Oleg Kalugin, former major general of the Committee for State Security (the KGB), has described sowing dissent as “the heart and soul” of the Putin state: not intelligence collection, but subversion – active measures to weaken the west, to drive wedges in the western community alliances of all sorts, particularly Nato, to sow discord among allies, to weaken the United States in the eyes of the people of Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and thus to prepare ground in case the war really occurs. To make America more vulnerable to the anger and distrust of other peoples.”

Churchill and Stalin in Moscow in 1942.

History is turned on its head. Not only is the fact that Russia was Britain’s ally in the war against Nazi Germany now a non-fact, but Russia it turns out is Nazi Germany’s heir, a fascist regime like Nazi Germany once was, posing a threat to Britain and the West like Nazi Germany once did.

Moreover who does not agree, and who does not see facing up to Russia as the priority, is at best a fool:

“In Brexit-voting Weymouth, Captain Malcolm Shakesby of Ukip is unruffled by Putin or European populism. He inhabits the cartoon world of British exceptionalism, and his main concern today is Mrs May’s “sellout” of the referendum result.”

Compare these comments about Russia in the staunchly anti-Brexit Guardian with these comments about Russia by Janet Daley in the staunchly pro-BrexitDaily Telegraph.

Janet Daley does not quite say like Hutton and Adonis that Russia is a “fascist regime”. However in her depiction of it she comes pretty close:

“The modern Russian economy is a form of gangster capitalism largely unencumbered by legal or political restraint. No one in the Kremlin pretends any longer that Russia’s role on the international stage is to spread an idealistic doctrine of liberation and shared wealth.

When it intervenes in places such as Syria, there is no pretence of leading that country toward a great socialist enlightenment. Even the pretext of fighting Isil has grown impossibly thin. All illusions are stripped away and the fight is reduced to one brutal imperative: Assad is Putin’s man and his regime will be defended to the end in order to secure the Russian interest. But what is that interest? Simply to assert Russia’s power in the world – which is to say, the question is its own answer.”

Though Moscow has made clear in both word and action that intervention in Syria at Syria’s invitation was to prevent it becoming a failed state and a terrorist haven, Russia it turns out is focused on only one thing: gaining as much power as possible. This is true both of its domestic politics (“gangster capitalism largely unencumbered by legal or political restraint”) and in its foreign policy (“what is that [Russian] interest? Simply to assert Russia’s power in the world – which is to say, the question is its own answer”)

As a result it must be construed as behaving in much the same way as Nazi Germany once did:

“…..we now seem to have the original threat from a rogue rampaging Russia back on the scene, too. A Russia determined to reinstate its claim to be a superpower, but this time without even the moral scruples of an ideological mission: the country that had once joined the respectable association of modern industrialised nations to make it the G8, rather than the G7, prefers to be an outlaw.”

On the question of the threat from Russia both the pro and anti-Brexit wings of the British establishment agree. Standing up to it is the one policy they can both agree on. Not surprisingly at every opportunity that is what they do.

Intolerance of Dissent Construed as a “Threat from Russia”

In this heavy atmosphere anyone in Britain who disagrees risks being branded either a traitor or a fool.

Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader, who is known to favour dialogue with Russia, recently had to endure an ugly media campaign which insinuated that he had been recruited as in effect a Communist agent in the 1980s by Czech intelligence.

That claim eventually collapsed when a British MP went too far and said openly what up to then had only been insinuated. As a result he was forced to retract his claims and pay compensation under threat of a law suit. However the question mark over Corbyn’s loyalty is never allowed to go away.

During last year’s general election Corbyn also had to endure an article in the Telegraph by none other than Sir Richard Dearlove, the former head of Britain’s external intelligence agency MI6 (the British equivalent of the CIA). Dearlove also insinuated that Corbyn had been at least a Communist sympathiser or fellow traveller during the Cold War whose sympathies were with the Eastern Bloc and therefore with the various anti-Western and supposedly Communist backed terrorist groups which the Eastern Bloc had supposedly supported:

“Today, Britain goes to the polls. And frankly, I’m shocked that no one has stood up and said, unambiguously, how profoundly dangerous it would be for the nation if Jeremy Corbyn becomes Prime Minister. So let me be clear, the leader of the Labour Party is an old-fashioned international socialist who has forged links with those quite ready to use terror when they haven’t got their way: the IRA, Hizbollah, Hamas. As a result he is completely unfit to govern and Britain would be less safe with him in No 10.

I can give an indication of just how serious this is: if Jeremy Corbyn was applying to join any of this country’s security services – MI5, GCHQ or the service I used to run, MI6 – he would not be cleared to do so. He would be rejected by the vetting process. Far from being able to get into MI5, in the past MI5 would actively have investigated him. And yet this is the man who seeks the very highest office, who hopes in just 24 hours time to run our security services.

Young people in Britain have been terribly affected by recent terror attacks. It is only natural that they should be desperately worried about security problems, and to me it is just such a great shame that they don’t understand the political antecedents of the Labour leader. It is these young people, in particular, I am keen to address. I want to explain just what Corbyn’s whole movement has meant.

During the Cold War the groups he associated with hung out in Algeria, and moved between East Germany and North Korea. It is hard, today, to understand the significance of that. When I talk to students about the Cold War, they assume I am just talking about history. But it has a direct bearing on our security today. Only a walk along the armistice line between North and South Korea, with its astonishing military build up, might give some idea of what was at stake.

……Jeremy Corbyn represents a clear and present danger to the country.”

In light of this the crescendo of criticism Corbyn came under during the peak of the uproar in March following the

Dearlove: Corbyn is a “clear and present danger” (to the establishment.)

Salisbury poisoning attack on Sergey and Yulia Skripal is entirely unsurprising.

Corbyn’s call – alone amongst senior politicians – for the investigation to be allowed to take its course and for due process to be followed, simply confirmed the doubts about his loyalty and his sympathy for Russia already held by the British establishment and previously expressed by people like Dearlove. His call was not seen as an entirely reasonable one for proper procedure to be followed. Rather it was seen as further proof that Corbyn’s sympathies are with Russia, which is Britain’s enemy.

Corbyn is not the only person to be targeted in this way. As I write this Britain is in the grip of a minor scandal because the right-wing businessman Arron Banks, who partly funded the Leave campaign during the 2016 Brexit referendum, is now revealed to have had several meetings with the Russian ambassador and to have discussed a business deal with a Russian businessman.

Though Banks claims to have reported these contacts to the CIA, and though there is not the slightest evidence of impropriety in any of these contacts (the proposed business deal never materialised) the mere fact that they took place is enough for doubts to be expressed about Banks’s reasons for supporting the Leave campaign. Perhaps even more worrying for Banks is that scarcely anyone is coming forward to speak up for him.

Even a politically inconsequential figure like the pop singer Robbie Williams is now in the frame. Just over a year ago Williams gained wide applause for a song “Party like a Russian” which some people interpreted (wrongly in my opinion) as a critique of contemporary Russia. Today he is being roundly criticised for performing in Russia during the celebrations for the World Cup.

Russophobia Undermining British Democracy

The result of this intolerance is a sharp contraction in the freedom of Britain’s public space, with those who disagree on British policy towards Russia increasingly afraid to speak out.

Since establishment opinion in Britain conceives of itself as defending liberal democracy from attack by Russia, and since establishment opinion increasingly conflates liberal democracy with its own opinions, it follows that in its conception any challenge to its opinions is an attack on liberal democracy, and must therefore be the work of Russia.

This paranoid view has now become pervasive. No part of the traditional media is free of it. It has gained a strong hold on the BBC and it is fair to say that all the big newspapers subscribe to it. Anyone who does not has no future in British journalism.

This is disturbing in itself, but as with all forms of institutional paranoia, it is also having a damaging effect on the functioning of Britain’s institutions.

Amid Growing Influence of Intelligence

One obvious way in which this manifests itself is in the extraordinary growth in both the visibility and influence of Britain’s intelligence services.

Historically the intelligence services in Britain have operated behind the scenes to the point of being almost invisible. Until the 1980s the very fact of their existence was in theory a state secret.

Today, as Dearlove’s article about Corbyn in the Daily Telegraph shows, their leaders and former leaders are not only public personalities, but the intelligence services have come increasingly to fill the role of gatekeepers, deciding who can be trusted to hold public office and who cannot.

Corbyn is far from being the only British politician to find himself under this sort of scrutiny.

Boris Johnson, some time before he became Britain’s Foreign Secretary, made what I am sure he now considers the mistake of writing an article in the Telegraph praising Russia’s role in the liberation of the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria from ISIS.

The result was that on his appointment as foreign secretary, Johnson had a meeting with British intelligence chiefs who ‘persuaded’ him of the need to follow a tough line with Russia. He has in fact followed a tough line with Russia ever since.

Russophobia Infects the Legal System

Steele: Paid for political research, not intelligence.

Establishment hostility to Russia is also enabling interference by the intelligence services in the British legal process.

There is a widespread and probably true belief that the British intelligence services actively lobbied for the grant of asylum to the fugitive Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky, who they seem to have considered some sort of ‘agent of influence’ in Russia. This despite the fact that it is now widely acknowledged that Berezovsky’s background and activities in Russia should have denied him asylum in Britain.

However what is still largely rumour in Berezovsky’s case is indisputable fact in the Alexander Litvinenko case and in the Skripal cases.

I have previously explained how in the Litvinenko case the claim of Russian state involvement in Litvinenko’s murder made by the British public inquiry is not supported by the publicly available evidence.

What has now become clear is that the main evidence of Russian state involvement in Litvinenko’s murder was not the publicly available evidence, but evidence provided to the public inquiry in private by the British intelligence services. This evidence was seen only by the Judge who headed the inquiry, but seems to have had a decisive effect in forming his view of the case and shaping his report.

American readers may be interested to learn that this evidence was put together by none other than Christopher Steele, the person who gave us the “golden showers” dossier, which has played such an outsized role in the Russiagate affair.

How strong or reliable this evidence is it is impossible to say since, as it is secret, it cannot be independently scrutinised. All I would say is that on two other occasions when Steele is known to have produced similar reports about Russian state activities subsequent enquiries have failed to support them. One is Steele’s “golden showers” dossier, which the FBI has admitted it cannot verify, and which scarcely anyone any longer believes to be true. The other is a report produced by Steele which alleged that Russia had bought the 2018 World Cup by bribing FIFA officials, which subsequent investigation has found was untrue.

It turns out that the evidence used to support the British claim of Russian guilt in the Skripal case is the same: evidence provided in private by British intelligence, which is not subject to independent scrutiny. As in the Litvinenko case, the British authorities have nonetheless not hesitated to use this evidence to declare publicly that Russia is guilty. This whilst a police investigation is still underway and before any suspect has been identified.

Indeed in the Skripal case the violation of due process has been so gross that it is not even denied. Instead articles have appeared in the British media which say that due process does not apply in cases involving Russia.

That there can be no rule of law without due process, and that excluding cases involving Russia from the need to follow due process is racist and discriminatory appears to concern no one.

Discrimination in Britain Against Russians

Where the intelligence services have led the way, others have been keen to follow.

Recently a House of Commons committee published a report which openly puts pressure on British law firms to refuse business from Russian clients. The best account of this has been provided by the Canadian academic Paul Robinson:

“……that leads me onto the thing which really struck me about this document [The House of Commons committee report – AM]. This was a statement about the British law firm Linklaters, which managed the flotation of EN+. Shortly before this, the report says ‘Both the EN+ IPO [Initial Public Offering] and the sale of Russian debt in London appear to have been carried out in accordance with the relevant rules and regulatory systems, and there is no obvious evidence of impropriety in a legal sense.’Yet, it then goes on to say the following:

“We asked Linklaters to appear before the committee to explain their involvement in the flotation of EN+ … They refused. We regret their unwillingness to engage with our inquiry and must leave others to judge whether their work at ‘the forefront of financial, corporate and commercial developments in Russia’has left them so entwined in the corruption of the Kremlin and its supporters that they are no longer able to meet the standards expected of a UK-regulated law firm.”

This is quite outrageous, and also cowardly. The committee in effect accuses Linklaters of corruption, while avoiding complaints of libel by use of the weasel words ‘we leave to others to judge’ – a way of making an accusation while claiming that one hasn’t. What’s so outrageous about the statement is that comes straight after a confession that the EN+ flotation was completely above board. Linklaters didn’t do anything wrong, and the House of Commons committee knows it. Nevertheless, it sees fit to suggest that the company is ‘no longer able to meet the standards expected of a UK-regulated law firm.’

The implication here is that any company which has extensive dealings with Russian enterprises is ‘entwined in the corruption of the Kremlin’and so unfit to do business. I cannot interpret this as anything other than an attempt by the committee to threaten British companies and intimidate them into dropping their lawful activities. I consider this disgraceful.

The committee’s attitude can be seen again towards the end of the report, when it writes that ‘instead of participating in the rules-based system, President Putin’s regime uses asymmetric methods to achieve its goals, and others – so-called useful idiots – magnify that effect by supporting its propaganda. So, there you have it. People who do with business with Russia are to be publicly shamed as unworthy of the standards expected of the British people, while those who would dare to point this sort of thing out are to be denounced as ‘useful idiots’. Having any dealings with Russia makes one a Kremlin stooge.”

Taking their cue from the House of Commons committee, identical pressure on British law firms to refuse to act for Russian clients is now coming from the media, as explained in this article by the Guardian’s Nick Cohen, which talks of potential Russian clients in these terms:

“In this conflict, it’s no help to think of oligarchs as businessmen. They are closer to the privileged servants of a warlord or mafia boss. Their wealth is held at Putin’s discretion. If they are told to buy influence in the Balkans or fund an alt-news website, they obey. Companies that raise funds on the London markets or oligarchs who move into Kensington mansions may look like autonomous organisations and individuals but, as Garry Kasparov told the committee: “They are agents of a rogue Russian regime, not businessmen. They are complicit in Putin’s countless crimes. Their companies are not international corporations, but the means to launder money and spread corruption and influence.”

To which I would add that in law-governed states even criminals have the right of legal representation and advice. In Britain, if the House of Commons committee and Nick Cohen gets their way, Russians – whether criminals or not – will be the exception.

What is so bizarre about this is that the spectre of massive Russian economic penetration of Britain conjured up by the House of Commons committee is so far removed from reality. The Economist (no friend of Russia) provides the actual figures:

“….the high profile of London’s high-rolling Russians belies the relatively small role that their money plays in the wider economy. Foreigners hold roughly £10 trillion of British assets. Russia’s share of that is just 0.25%, a smaller proportion than that of Finland and South Korea.

Parts of west London have acquired many new Russian residents, and shops to serve them (including an outfitter of armoured luxury cars). Yet even in “prime” London – that is, the top 5-10% of the market – buyers from eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union account for only 5% of sales, according to data from Savills, a property firm. Outside the capital’s swankiest districts, Russians’ influence is minuscule. The departure of oligarchs might affect prices on some streets in Kensington, but not beyond.

The same is true of Britain’s private schools. Some have done well out of Russian parents. But of the 53,678 foreign pupils who attend schools that belong to the Independent Schools Council, only 2,806 are Russian. China, by contrast, sends 9,008 pupils from its mainland, and a further 5,188 from Hong Kong.

Looking at these figures it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that it is the mere presence of Russians, not their number or their wealth or the illicit way in which some of them supposedly came by their money, which for the British establishment is the problem.”

Quite simply, Russians are not welcome, not because they are wealthy or because they are corrupt, but because they are Russians.

Against Russian Media

The same discriminatory approach appears to inform the persistent attacks launched by the British authorities against the Russian television broadcaster RT.

Over the last two years RT has had to repel an attempt by the British authorities to close down its British bank account, has been forced to respond to a succession of complaints from the British media regulator Ofcom, has faced threats of having its British broadcasting licence withdrawn, and has had to endure a campaign of vilification aimed in part at dissuading British public figures from appearing as guests on its programmes.

As to what exactly RT has done – other than vague and unspecific claims that it is a ‘propaganda’ channel – which justifies this treatment, has never been fully explained.

Again it is difficult to avoid the impression that the British establishment’s fundamental problem with RT is that it is simply a Russian channel broadcasting in Britain that scrutinizes establishment policies and actions – a fundamental responsibility of journalism, which is largely missing in British media.

Free speech is a human right in Britain except apparently for Russians.

This discriminatory approach towards Russia and Russians replicates the increasingly ugly and frankly racist way in which Russians are regularly depicted in Britain today.

As to the general effect of that on British society, I repeat here what I wrote back in 2016:

“Racial stereotyping is always something to complain about. It is dehumanising, intolerant and ugly. It is racist and profoundly offensive of its target. This is so whenever it is used to mock or label any ethnicity or national or cultural group. Russians are not an exception.

A society that indulges in it, and which tolerates those who do, forfeits its claim to anti-racism and interracial tolerance. The fact that it is treating just one ethnic group – Russians – in this way, denying them the moral and legal protection which it accords others, in no way diminishes its racism and intolerance. It emphasises it.”

British society is not just the poorer for it. It is deeply corrupted by it, and this corruption now touches every aspect of British life.

Britain Becoming Marginalised

If the result of the British establishment’s paranoia about Russia is deeply corrosive within Britain itself, its effect on British foreign policy has been entirely negative.

At its most basic level it has meant a total breakdown in relations between Britain and Russia.

British and Russian leaders no longer talk to each other, and summit meetings between British and Russian leaders have come to a complete stop. Boris Johnson’s last visit to Russia is universally acknowledged to have been a complete failure, and following the Skripal affair British officials and members of Britain’s Royal Family are now even boycotting the World Cup in Russia.

Indeed British public statements about the World Cup have been all of a piece with the British establishment hostility to Russia, with Johnson recently comparing it to Hitler’s 1936 Olympics and with another House of Commons committee warning British fans of the supposed dangers of going to to Russia to watch them.

This complete absence of dialogue with Russia is a serious problem for Britain as some British officials quietly acknowledge.

Russia is after all a powerful nation and any state which still wishes to exercise influence on world affairs must engage with Russia in order to achieve it. The British establishment’s hostility to Russia however makes that impossible.

The result is that major international questions such as the Ukrainian crisis, the Syrian conflict and the gathering crisis in the Middle East caused by the U.S.’s withdrawal from the Iranian nuclear deal – in all of which Russia is centrally involved – are being handled without British involvement.

May: Becoming a bit player.

Where Angela Merkel of Germany and Emmanuel Macron of France talk to Russia and have thereby managed to carve out for themselves important roles in world affairs, Britain’s Theresa May is a bit player.

However, instead of drawing the obvious conclusion from this, which is that refusing to talk to the Russians is the high road to nowhere, the British have doubled down, seeking to regain relevance by leading an international crusade against Moscow.

The strategy – which bears the unmistakeable imprint of Johnson – was set out in grandiose terms in a recent article in The Guardian:

“The UK will use a series of international summits this year to call for a comprehensive strategy to combat Russian disinformation and urge a rethink over traditional diplomatic dialogue with Moscow, following the Kremlin’s aggressive campaign of denials over the use of chemical weapons in the UK and Syria.

British diplomats plan to use four major summits this year – the G7, the G20, Nato and the European Union – to try to deepen the alliance against Russia hastily built by the Foreign Office after the poisoning of the former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal in Salisbury in March.

“The foreign secretary regards Russia’s response to Douma and Salisbury as a turning point and thinks there is international support to do more,” a Whitehall official said. “The areas the UK are most likely to pursue are countering Russian disinformation and finding a mechanism to enforce accountability for the use of chemical weapons.”

Former Foreign Office officials admit that an institutional reluctance to call out Russia once permeated British diplomatic thinking, but say that after the poisoning of Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, that attitude is evaporating…..

Ministers want to pursue a broad Russian containment strategy at the coming summits covering cybersecurity, Nato’s military posture, sanctions against Vladimir Putin’s oligarchs and a more comprehensive approach to Russian disinformation.”

It has taken no more than a few weeks since that article appeared on 3 May 2018 for this whole grandiose strategy to fall apart.

Not only have Merkel and Macron each visited Russia since the article was published, but Italy now has a new Russia-friendly government, and Spain may soon do so also. Adding insult to injury, Germany is now casting doubt on Britain’s actions following the Salisbury poisoning attack,

All of this however is eclipsed by Donald Trump’s comments at the G7 saying that Russia should be readmitted to the G7 and having his officials inform the British media that he is becoming increasingly irritated by the British prime minister’s lectures.

In the event not only did Trump fail to meet May one-to-one at the G7 summit, but he refused to agree the summit’s final communique, which criticised Russia.

Needless to say, amidst the collapse of the summit, the plan May had apparently intended to unveil at the summit for anew international rapid response unit to respond to Russian-backed assassinations and cyber attacks fell by the wayside.

Far from gaining relevance by leading an international crusade against Russia, the British are increasingly finding that no one else is interested and that May’s and the British establishment’s obsession with Russia instead of enhancing Britain’s importance is making Britain increasingly irrelevant.

Poisoning the International Atmosphere

The British establishment is in fact making the fundamental mistake of thinking that other countries not only share their obsession with Russia, but that they necessarily value their relations with Britain more than with Russia.

This is a strange view given that Russia is arguably a more powerful nation than Britain.

It is nonetheless true that the British establishment’s anti-Russian fixation is having an internationally damaging effect.

Many Western governments have their own issues with Russia, and in such a situation it is not surprising that British paranoia about Russia finds a ready echo.

The most recent example of this is of course the orchestrated expulsion by various Western governments of Russian diplomats in the immediate aftermath of the Salisbury poisoning attack.

However the most damage has been done in the U.S.

Britain and Russia-gate

The full extent of the British role in the Russiagate scandal is not yet clear, but there is no doubt that it was both extensive and crucial.

The individual who arguably has played the single biggest role in generating the scandal is Christopher Steele, the compiler of the “golden showers” dossier, who is not only British but who is a former British intelligence officer.

It is now becoming increasingly clear – as Joe Lauria wrote last year in Consortium News– that the dossier has played a key role in the whole scandal, being accepted for many months by U.S. investigators – including it turns out by Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigators – as providing the ‘frame-narrative’ for the case of alleged collusion between the Russians and the Trump campaign.

The Steele dossier is in fact very much of a piece with the paranoid conception of Russia which has taken hold in Britain, though (as I have pointed out previously) the dossier’s description of how government decisions are made in Russia isabsurd.

Critics of the dossier in the United States rightly draw attention to the fact that it is ‘research’ paid for by Donald Trump’s political opponents in the Hillary Clinton campaign, whilst there is also a view popular amongst some Republicans (wrongly in my opinion) that it is a provocation concocted by Russian intelligence in order to disrupt the U.S. election process and embarrass Trump.

By contrast, insufficient attention is paid, in my opinion, to the fact that it is a British compilation put together in Britain by a former British spy at a time when Britain is in the grip of a particularly bad bout of Russia paranoia.

Steele himself is someone who by all accounts has fully bought into this paranoia. Indeed his previous role in preparing reports about Russia’s supposed role in Litvinenko’s murder and the World Cup bid, and also apparently in the Ukrainian crisis, suggests that he has played no small role in creating it.

Steele is not however the only British official or former official to have played an active role in Russia-gate.

Steele himself is known for example to have a close connection to Dearlove, the former MI6 Director who called Corbyn “a clear and present danger.” It seems that Dearlove and Steele discussed the “golden showers” dossier at a meeting in London’s Garrick Club at roughly the same time that Steele was in contact about it with the FBI.

Another far more more important British official to have taken an active role in the Russiagate affair was Robert Hannigan, the head of GCHQ – Britain’s equivalent to the NSA – who visited the U.S. in the summer of 2016 to brief the CIA about British concerns over alleged contacts between the Russians and Trump’s campaign.

Hannigan: Brought Steele dossier to the CIA.

Though Hannigan’s trip to Washington in the summer of 2016 was first spoken of in April 2017, it has never been confirmed that the Steele dossier, which he brought with him to show to the CIA, was part of the evidence of supposed contacts between the Russians and Trump’s campaign. That it was, however, is strongly suggested by an article in The Washington Post on June 23, 2017, which amongst other things said the following:

“Early last August, an envelope with extraordinary handling restrictions arrived at the White House. Sent by courier from the CIA, it carried “eyes only” instructions that its contents be shown to just four people: President Barack Obama and three senior aides.

Inside was an intelligence bombshell, a report drawn from sourcing deep inside the Russian government that detailed Russian President Vladimir Putin’s direct involvement in a cyber campaign to disrupt and discredit the U.S. presidential race.

But it went further. The intelligence captured Putin’s specific instructions on the operation’s audacious objectives — defeat or at least damage the Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, and help elect her opponent, Donald Trump…..

The CIA breakthrough came at a stage of the presidential campaign when Trump had secured the GOP nomination but was still regarded as a distant long shot. Clinton held comfortable leads in major polls, and Obama expected that he would be transferring power to someone who had served in his Cabinet.

The intelligence on Putin was extraordinary on multiple levels, including as a feat of espionage.

For spy agencies, gaining insights into the intentions of foreign leaders is among the highest priorities. But Putin is a remarkably elusive target. A former KGB officer, he takes extreme precautions to guard against surveillance, rarely communicating by phone or computer, always running sensitive state business from deep within the confines of the Kremlin.”

This almost certainly refers to the early entries of Steele’s dossier, which is the only report known to exist which claims to have been “sourc[ed from] deep inside the Russian government [and to have detailed] Russian President Vladimir Putin’s direct involvement in a cyber campaign to disrupt and discredit the US Presidential race”.

The Washington Post says that the CIA’s report to Obama drew on “critical technical intelligence on Russia provided by another country”.

That points to Hannigan being the source, with Hannigan being known to have visited the U.S. and to have briefed the CIA at about the time the CIA sent its report to Obama.

Hannigan likely provided the CIA with a mix of wiretap evidence and the first entries of the dossier.

The wiretap evidence probably detailed the confused but ultimately innocuous contacts the young London- based Trump campaign aide George Papadopoulos was having at this time with the Russians. It is highly likely the British were keeping an eye on him at the request of the U.S., which the British would have been able to do for the U.S. without a FISA warrant since Papadopoulos was based in Britain.

Taken together with the first entries of the dossier, the details of Papadopoulos’s activities could easily have been misconstrued to conjure up a compelling case of collusion between the Trump campaign and the Russians. Given the paranoid atmosphere about Russia in Britain it would not be surprising if this alarmed Hannigan.

Needless to say if extracts from the dossier really were provided to the CIA by the head of one of Britain’s most important intelligence agencies, then it becomes much easier to understand why the CIA and the rest of the U.S. intelligence community took it so seriously.

Halper: Infiltrated Carter and Trump campaigns.

Then there is the case of Stefan Halper, an American academic lecturing at Cambridge University, who is friends and a business partner with Dearlove. Halper was inserted by the FBI into the Trump campaign in early July 2016 to befriend Papadopoulos in London. In 1980, the CIA inserted Halper into Jimmy Carter’s reelection campaign to help the Reagan camp by stealing information, including a Carter briefing book before a presidential debate.

Suffice to say that just as the British origin of the dossier has in my opinion been overlooked, so has the extent to which it circulated and was given credence in top circles within Britain before it made its full impact in the United States.

Overall, though the extent of the British role in the Russiagate affair is still not fully known, what information exists points to it being very substantial and important. In fact it is unlikely that the Russiagate scandal as we know it would have happened without it.

As such the Russiagate scandal serves as a good example of how British paranoia about Russia can infect the political process in another Western country, in this case the U.S.

Campaigning against Russia

Russia-gate is in fact only the most extreme example of the way that Britain’s anti-Russian obsession has damaged the international environment, though because of the effect it has had on the development of domestic politics in the United States it is the most important.

There have been countless others. The British have for example been the most implacable supporters amongst the leading Western powers of the ongoing sanctions drive against Russia. Britain for instance is known to have actively – though so far unsuccessfully – lobbied for Russian banks to be cut off from the SWIFT interbank payments system, which were it ever to happen would be by far the most severe sanction imposed by the West on Russia to date.

Beyond the effect on the international climate of the constant anti-Russian lobbying of the British government, there is the further effect of the ceaseless drumbeat of anti-Russian agitation which pours out of the British media and various British-based organisations and NGO.

These extend from well-established organisations like Amnesty International – which misrepresented the case against the Pussy Riot performers by claiming that they had been jailed for “holding a gig in a church” – to other less established organisations such Bellingcat and the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, both of which are based in Britain. As it happens, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights is known to have received funding from the British government, as apparently have the White Helmets.

In addition Bill Browder, the businessman who successfully lobbied the U.S. Congress to pass the Magnitsky Act, and who has since then pursued a relentless campaign against Russia, is now also based in Britain and has British citizenship.

The great international reach of the British media – the result of the worldwide use of the English language and the international respect some parts of British media such as the BBC still command – means that this constant stream of anti-Russian publicity pouring out of Britain has a worldwide impact and is having an effect that has to be taken into account in any study of current international relations.

Rami Abdul Rahman: The one-man Observatory

The Price of an Obsession

The British establishment’s obsession with Russia is something of a puzzle.

Britain today is not a geopolitical rival of Russia’s as it was in the nineteenth century and as the U.S. is today. British antagonism to Russia cannot therefore be explained as the product of a geopolitical conflict.

Russia is not a military or political threat to Britain. There is no history of Russia threatening or invading Britain. Russia is not an economic rival, and Russian penetration of the British economy is minimal and vastly exaggerated.

It is sometimes said that there are things about modern Russia that the British find culturally, ideologically or politically distasteful, and that this is the reason for Britain’s intense hostility to Russia. However Britain has no difficulty being best of friends with all sorts of countries such as the Gulf Monarchies or China which are culturally, ideologically and politically far more different from Britain than Russia is. Logically that should make them more distasteful to Britain than Russia is, but it doesn’t seem to do so. In these cases economic interests clearly take precedence over any concerns for human rights.

Ultimately however the precise cause of the British establishment’s obsession with Russia does not actually matter. What does matter is that it is an obsession, which should be recognised as such, and that like all other obsessions is ultimately destructive.

In Britain’s case the obsession is not only corrupting Britain’s domestic politics and the working of its institutions.

It is also marginalising Britain, limiting its options, and causing growing exasperation amongst some of its friends.

In addition it blinds the British to their opportunities. If the British were able to put their obsession with Russia behind them they might notice that at a time when they are quitting the European Union Russia potentially has a great deal to offer them.

It is sometimes said that Britain produces very little that Russia needs, and it is indeed the case that trade between Russia and Britain is very small, and that most of Russia’s import needs are met by countries like Germany and China.

However Britain is able to provide Russia with the single thing that Russia arguably needs most at this stage in its development. This is not machinery or technology, all of which it is perfectly capable of producing itself, but the one thing it is truly short of: investment capital.

In the nineteenth century British capital played a key role in the industrialisation of America and in the opening up of the American West. There is no logical reason why it could not do something similar today in Russia. Indeed the marriage between Europe’s biggest financial centre (Britain) and Europe’s potentially most productive economy (Russia) is an obvious one.

In the twentieth century Britain’s long history of economic involvement in the U.S. paid handsome political dividends. Perhaps the same might one day be the case between Britain and Russia. Regardless of that, economic engagement with Russia would at least provide Britain with a plan for an economic future outside the EU, something which because of Brexit it urgently needs but which currently it completely lacks.

For anything like that to happen the British will first have to address the reality of their obsession, and the damage it is doing to them. At that point they might even start to do something about it. Britain’s relative success since the 1960s in overcoming other forms of racism and prejudice which had long existed in Britain shows that such a thing is possible if the problem is recognised and addressed. However I have to say that there is no sign of it happening at the moment.

In the meantime the rest of the world needs to understand that when it comes to Russia, the British are suffering from a serious affliction. Failing to do that risks the infection spreading, with the disastrous consequences we have seen with the Russia-gate scandal in the US.

There is even a chance that refusing to listen to the British about Russia might have a good effect on Britain. If the British realise that the world is no longer listening to them then they might start to understand the extent of their own problem.

If so than the world would be doing Britiain a favour, even if at the moment the British cannot see it.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2HS44zT Tyler Durden