Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

Just recently, David Robertson ran an article discussing the deviation which has grown between “fantasy” and “reality” in the investing markets.

“The phenomenon of extreme differences is also increasingly appearing in financial numbers, which are the life blood of markets. Andrew Smithers conducted research on the usefulness of accounting numbers and his work was summarized by Jonathan Ford.

‘Corporate data now provide worse information than before.’

The ironic consequence of all this is that investors increasingly rely on non-Gaap numbers for valuation. These are not only idiosyncratic, and thus not always capable of comparison, they are also devised by bosses whose views may well be richly coloured by their own outsize incentives.’

Henny Sender highlights some prominent examples of “unusual measures of corporate performance.” Specifically, she mentions “gross merchandise value” as a metric commonly used by e-commerce firms and “community adjusted” earnings which is a controversial metric recently introduced by WeWork.

The entire article is a great read. However, what struck a cord with me was it brought up the memories of the late 1998-2000 bull market run when start up-IPO internet companies were being valued with “eyeballs per page” since most traditional measures of profitability, such as cash flows, earnings, and revenue were non-existent.

I know…most of you reading this article probably weren’t investing in the late 90’s, however, the few of you who were in the trenches with me will remember it all to well. Names like Enron, Worldcom, Global Crossing, Lucent Technologies, and a vast graveyard of others have long been forgotten and are now ancient artifacts of an age gone by.

Much like then, today we see companies going public like Lyft, Uber, Instagram, and others who have massive cash burn rates, little to no prospect for profitability in the near future, and astronomical valuations. Companies that are public, like Facebook (FB), are valued on “Monthly Average Users” or “MAU’s” which is highly suspect given that studies have suggested that as much as 50% of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube’s users may be “fake.” Further, there is no verification process for what constitutes a valid account and as such, the stats are mostly just taken at the companies word. Importantly, the point is that creative use of new “metrics” are being used to justify valuations to satiate investor appetites.

Much like the late 1990’s, no one “really” wants to know the real answer, they just want to buy high and sell higher.

This is what Wall Street does, and does very well, as David noted in his missive.

“The potential to create a very misleading impression of financial condition with alternative metrics was the subject of a report on the cloud software industry in the FT’s Alphaville. The article highlights the fact that the average free cash flow margin for the cloud companies is 8.6% which is impressive. However, that margin falls to a far less impressive -0.6% when the real expenses of stock compensation are included.

At the end of the day, alternative metrics like these are better designed to tell stories than to provide information content. Sender notes, rightly, that such alternative measures “are no substitutes for profits or a path to them.” As the Alphaville report also points out, however, ‘Investors don’t seem to care that much.’”

Well, they may not care much at the moment.

But they will.

If You Can’t Make It, Fake It?

I just recently reviewed the latest completed earnings season (Q4). As has become the norm, companies once again beat drastically lowered earnings estimates with a variety of measures. To wit:

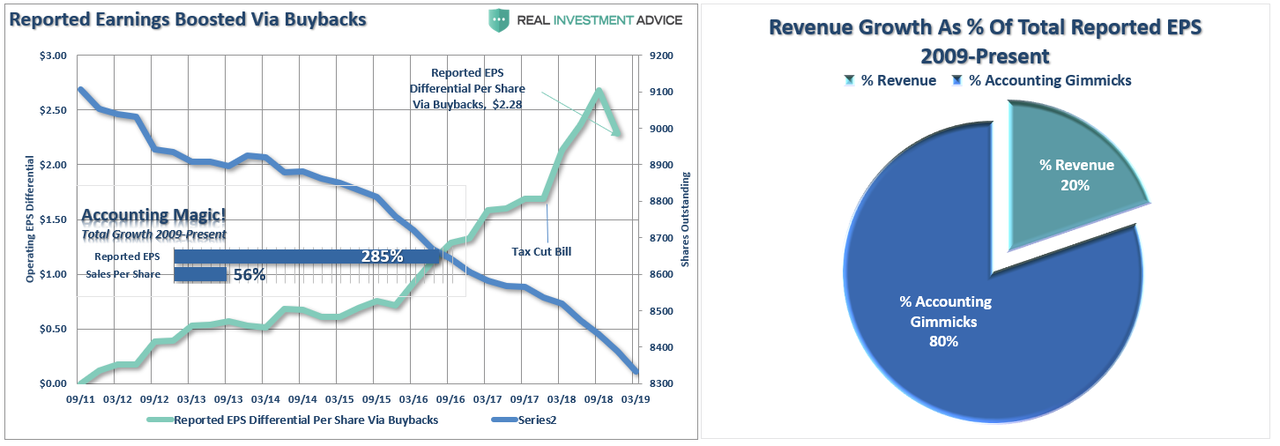

“Since the recessionary lows, much of the rise in “profitability” have come from a variety of cost-cutting measures and accounting gimmicks rather than actual increases in top-line revenue. While tax cuts certainly provided the capital for a surge in buybacks, revenue growth, which is directly connected to a consumption-based economy, has remained muted.

Since 2009, the reported earnings per share of corporations has decreased from 353% in Q2-2018 to just 285% in Q4. However, even with the recent decline, this is still the sharpest post-recession rise in reported EPS in history.

Moreover, the increase in earnings did not come from a commensurate increase in revenue which has only grown by a marginal 56% during the same period. (Again, note the sharp drop in EPS despite both tax cuts and massive share buybacks. This is not a good sign for 2019.)”

The reality is that stock buybacks create an illusion of profitability. Such activities do not spur economic growth or generate real wealth for shareholders, but it does provide the basis for with which to keep Wall Street satisfied and stock option compensated executives happy.

However, the recent downturn in corporate profitability may be more than just due to an economic “soft patch” as currently suggested by the majority of Wall Street analysts. The problem with cost cutting, wage suppression, labor hoarding and stock buybacks, along with a myriad of accounting gimmicks, is that there is a finite limit to their effectiveness and a long term cost that must eventually be paid.

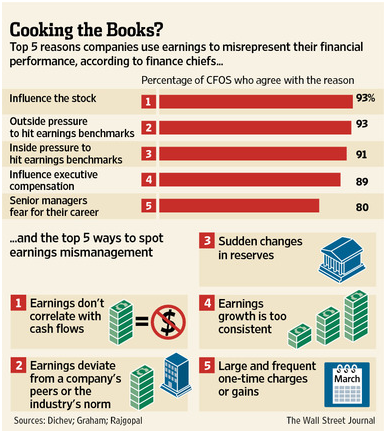

Wall Street is well aware that “missing earnings,” even by the slightest margin, can have an extremely negative impact on their current share price. As such, it should come as no surprise that companies manipulate bottom line earnings to win the quarterly “beat the estimate” game. By utilizing “cookie-jar” reserves, heavy use of accruals, and other accounting instruments they can mold earnings to expectations.

“The tricks are well-known: A difficult quarter can be made easier by releasing reserves set aside for a rainy day or recognizing revenues before sales are made, while a good quarter is often the time to hide a big ‘restructuring charge’ that would otherwise stand out like a sore thumb.

What is more surprising though is CFOs’ belief that these practices leave a significant mark on companies’ reported profits and losses. When asked about the magnitude of the earnings misrepresentation, the study’s respondents said it was around 10% of earnings per share.“

It should not be surprising that more than 90% of the companies surveyed pointed to “influence on stock price” and “outside pressure” as reasons for manipulating earnings.

Note: For fundamental investors this manipulation of earnings skews valuation analysis particularly with respect to P/E’s, EV/EBITDA, PEG, etc.

A couple of years ago, the Associated Press has a fantastic article entitled: “Experts Worry That Phony Numbers Are Misleading Investors:”

“Those record profits that companies are reporting may not be all they’re cracked up to be.

As the stock market climbs ever higher, professional investors are warning that companies are presenting misleading versions of their results that ignore a wide variety of normal costs of running a business to make it seem like they’re doing better than they really are.

What’s worse, the financial analysts who are supposed to fight corporate spin are often playing along. Instead of challenging the companies, they’re largely passing along the rosy numbers in reports recommending stocks to investors.“

Here are the key findings of the report:

-

Seventy-two percent of the companies reviewed by AP had adjusted profits that were higher than net income in the first quarter of this year. That’s about the same as in the comparable period five years earlier, but the gap between the adjusted and net income figures has widened considerably: adjusted earnings were typically 16 percent higher than net income in the most recent period versus 9 percent five years ago.

-

For a smaller group of the companies reviewed, 21 percent of the total, adjusted profits soared 50 percent or more over net income. This was true of just 13 percent of the group in the same period five years ago.

-

Quarter after quarter, the differences between the adjusted and bottom-line figures are adding up. From 2010 through 2014, adjusted profits for the S&P 500 came in $583 billion higher than net income. It’s as if each company in the S&P 500 got a check in the mail for an extra eight months of earnings.

-

Fifteen companies with adjusted profits actually had bottom-line losses over the five years. Investors have poured money into their stocks just the same.

-

Stocks are getting more expensive, meaning there could be a greater risk of stocks falling if the earnings figures being used to justify buying them are questionable. One measure of how richly priced stocks are suggests trouble. Three years ago, investors paid $13.50 for every dollar of adjusted profits for companies in the S&P 500 index, according to S&P Capital IQ. Now, they’re paying nearly $18.

The obvious problem, when it comes to investing in individual companies, is that playing “leapfrog with a unicorn,”pun intended, ultimately has very negative outcomes. While valuations may not matter currently, in hindsight it will become clear that such valuation levels were clearly unsustainable. However, by the time the financial media reports such revelations it will be long after it matters to anyone.

As David noted in his article, it is important to be aware of the difference, and ultimately what constitutes, “Fantasy”and “Reality.” Most portfolio managers are using valuation measures today based on recent 5- or 10-year averages, or worse, forward “operating earnings.” They will be unpleasantly surprised by the depth of the reversion when it eventually comes.

A couple of years ago, Wade Slome, penned an excellent article pointing out four things to look for when analyzing corporate earnings:

-

Distorted Expenses: If a $10 million manufacturing plant is expected to last 10 years, then the depreciation expense should be $1 million per year. If for some reason the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) suddenly decided the building would last 40 years rather than 10 years, then the expense would only be $250,000 per year. Voila, an instant $750,000 annual gain was created out of thin air due to management’s change in estimates.

-

Magical Revenues: Some companies have been known to do what’s called ‘stuffing the channel.’ Or in other words, companies sometimes will ship product to a distributor or customer even if there is no immediate demand for that product. (Think Autos) This practice can potentially increase the revenue of the reporting company, while providing the customer with more inventory on-hand. The major problem with the strategy is cash collection, which can be pushed way off in the future or become uncollectible.

-

Accounting Shifts: Under certain circumstances, specific expenses can be converted to an asset on the balance sheet, leading to inflated EPS numbers. A common example of this phenomenon occurs in the software industry, where software engineering expenses on the income statement get converted to capitalized software assets on the balance sheet. Again, like other schemes, this practice delays the negative expense effects on reported earnings.

-

Artificial Income: Not only did many of the troubled banks make imprudent loans to borrowers that were unlikely to repay, but the loans were made based on assumptions that asset prices would go up indefinitely and credit costs would remain freakishly low. Based on the overly optimistic repayment and loss assumptions, banks recognized massive amounts of gains which propelled even more imprudent loans. That said, relaxation of mark-to-market accounting makes it even more difficult to estimate the true values of assets on the bank’s balance sheets.

These points are more valid today than they were then. The abuses to financial statements to meet earnings estimates have continued to grow. However, most investors don’t look beyond the media headlines before click the “buy” button on the latest “bull call de jour” on CNBC.

However, for longer term investors who are depending on their “hard earned” savings to generate a “living income” through retirement, understanding the “real” value of a stock will mean a great deal. Unfortunately, there are no easy solutions, on-line tips or media advice will not supplant rolling up your sleeves and doing your homework.

Investors would do well to remember the words of the then-chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission Arthur Levitt in a 1998 speech entitled “The Numbers Game:”

‘While the temptations are great, and the pressures strong, illusions in numbers are only that—ephemeral, and ultimately self-destructive.’”

The reality is that this “time is NOT different.” The eventual outcome will be the same as every previous speculative/liquidity driven bubble throughout history. The only difference will be the catalyst that eventually sends investors running for cover.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2IFsHAn Tyler Durden