“Platforms don’t look like how they work and don’t work like how they look.” – Benjamin H Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty

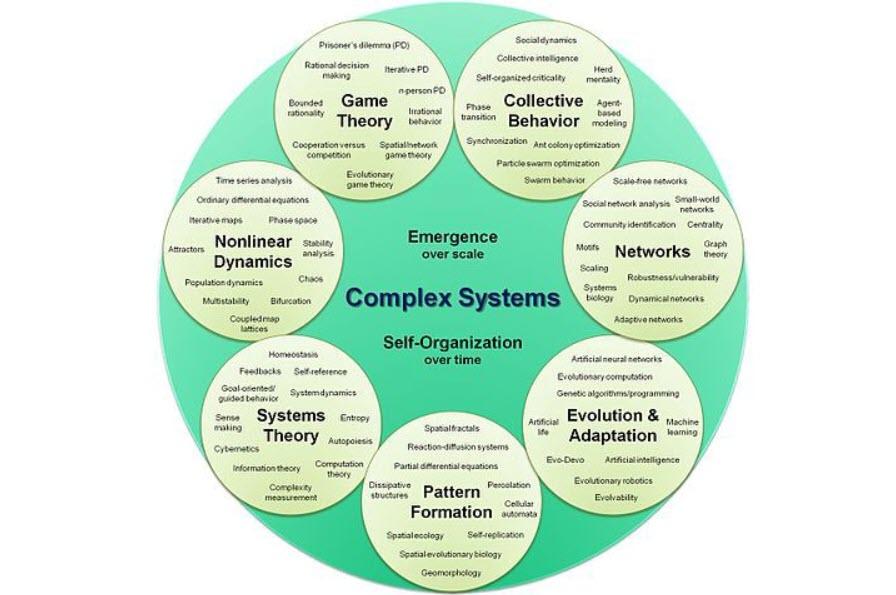

Complex systems by their very nature are, of course, complex. As Sayama’s diagram at the opening of this post demonstrates…

An elementary definition of a complex system is one that is constituted of multifarious units (often simple), interacting with each other in abstruse patterns, which in turn, makes them inherently difficult to model. This difficulty in the modelling process is due to properties that such systems manifest, including emergence, cybernetic feedback loops, adaptation, non-linearity and self-organization. Some common examples include transport networks, biological systems and power grids.

Trans-Continental, technomic, complex systems that encompass nested technomic systems as constituent parts, obviously are recursively complex themselves. From the smallest economic system, recursively building upon themselves we see the emergence of the networks that underlay a socioeconomic structure such as the EU. In other words, the complex systems we see at the state level, manifest at the trans-state level. Take your country’s power grid and scale it up across a continent.

From 1950 onward numerous treaties were signed among European governments, giving birth to the EEC, EEA, Schengen and ultimately the EU. Each set of agreements allowed for evermore emergent properties to manifest. Each overlapping treaty, in turn, allowed for a convergence of networks. Consequently, existing systems became further embedded in a fashion that is difficult to discern until attempting to pry them apart.

And there lies the fundamental problem, with the understanding that many Brexit supporting politicians have of the EU.

To me, Brexit is easy – Nigel Farage, 20 September 2016

Very often the platform does not look like how it works. In the case of the EU, it may appear as simply a group of trade treaties binding together a set of sovereign nation states.

Now, of course, this certainly an aspect of it. What can’t be perceived by simply looking at the platform i.e. the aggregate of treaties and agreements, is the emergent and self-organizing qualities of the European project.

The EU and related interconnecting bodies have become an astonishingly complex interplay of elements that have fed off the evolution of human society, its scientific discoveries, engineering marvels and social transformations.

Power to the people

One such example is the synchronous grid of Continental Europe also known by the acronym CSA (Continental Synchronous Area). Supplying over 400 million customers across 24 EU member states, and running at a phase-locked 50 Hz mains frequency, it forms the largest synchronous electricity grid on earth. It’s formed part of a push towards an internal European energy network and market and also aimed to harmonize with grids located outside of Europe, including those located in North Africa.

This is a concrete realization of the concept of the energy-information networks that underpin the Earth layer of Benjamin Bratton’s Stack.

“… energy-information networks … are central to how the Earth layer functions within The Stack — Benjamin Bratton. The Stack | On Software and Sovereignty”

The CSA which encompasses elements of this layer forms the precursor to the European super grid, which would include not just the various grids in Europe, but those in the mentioned neighbouring areas too.

The UK is not currently apart of the CSA directly but connects to it via the HVDC Cross-Channel link and BritNed (a submarine cable from Kent to Massvlakte). This is known as an electricity island network and has counterparts with Nordic regional group and Baltic regional group.

The body behind the CSA is the ENTSO-E or European Network of Transmission System Operators. This currently represents 36 nation states across Europe (some of which lay outside the EU’s borders). ENTSO-E was established and given a legal mandate by the EU itself, via the Third Package for the Internal Energy market in 2009, but is self-funded by member states. The United Kingdom is represented at ENTSO-E by the National Grid, SONI, SHETransmission and SPTransmission.

So what will be the relationship between ENTSO-E and the UK post-Brexit? Well, it appears nobody actually knows yet. Here is Montel News discussing the subject in August of 2018:

Brexit could overhaul energy relations between the UK and the EU, derailing plans to increase market coupling with the UK and boost investment in interconnectors. — TSOs ready for no-deal Brexit — Entso-E, Montel.

How would the UK remain a part of this body?

Analysts believe the UK can remain a part of the internal energy market as a third country if the British government accept the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice. — TSOs ready for no-deal Brexit — Entso-E, Montel.

And thus the double-bind. The half-cyborg-half-human, British Prime Minister, known as Theresa May by some and the Maybot by others, has already ruled this out. In a paper published in 2017 May’s government had stated the jurisdiction of the ECJ will come to an end with Brexit.

In leaving the European Union, we will bring about an end to the direct jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). — Enforcement and dispute resolution, A Future Partnership Paper — HM Government

As the Montel News article notes, the former Tory politician Tim Yeo told said news agency that leaving the EU internal energy market would force the UK government to complete Hinkley Point nuclear power plant.

But this path leads us into yet another conundrum — Euratom.

The European Atomic Energy Community, better known as Euratom, has its origins in the late 1950s. Its goal was to create an internal market for nuclear power and to then trade any excess to non-market members. Since then it has gone on to concern itself with providing a basis for regulating civil nuclear material and also controlling the supply of fissile materials within the EU.

While Euratom is closely linked to the EU including governance by some of the EU’s institutions it sits outside of the control of the European Parliament and is a legally distinct entity. Thus leaving the EU does not mean one has to leave Euratom.

Adam Vaughan writing for the Guardian in 2017 discussed the problematic situation of the UK leaving this agency, which it intends to do as part of the exiting process:

Failure to put in place alternative arrangements to replace the existing European nuclear treaty, Euratom, which the UK is quitting as part of the article 50 process, would have a “dramatic impact” on Hinkley Point C and other new power stations around the country, the industry said. — Adam Vaughan

It was not until after the referendum the impact of leaving the institution was assessed in the Common Briefing papers CBP-8036.

As of November 2018, exiting still seemed to be in the works and the draft treaty spells out as much. A December 2018 joint statement fleshed out commitments on the behalf of the UK to align its nuclear safeguards with that of Euratom. The devil as ever will be in the detail here. And if May’s deal is rejected? Well….

Many shrewdly will be asking, why exactly is the UK leaving Euratom anyway regardless of what deal is struck?

“It is simply bonkers to leave Euratom,” says Steven Cowley, a theoretical physicist at the University of Oxford who until last year was director of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy, which hosts JET. — Nature.com

Bonkers indeed.

In addition to Hinkley Point C, the mentioned JET project centred on Nuclear Fusion experiments, and based in Oxfordshire had no idea if its EU funding (which forms the bulk) would be replaced by equal UK funding. And truth be told, it’s still not concrete.

Following the impact and confusion Brexit is having on such a fundamental part of the UK’s infrastructure, one has to wonder if anyone in the UK government had actually thought about this prior to triggering article 50?

* * *

And there we have it, even with May’s deal, confusion reigns supreme. Yet according to the Prime Minister, the commons should vote to support her deal, which relies on promises of alignment and funding for Nuclear operations but mentioned nothing of ENTSO-E. Or to quote her retort to Ian Blackford MP:

“He should vote for a deal — simples.” – May aide won bet with Pm’s ‘simple’ comment:report. Politico

It is doubtful that there is a single soul in Europe who can grok the complexity of the EU now, let alone any British politician advocating for exiting it. Pelle Neroth captures the complexity pointedly in this quote:

The EU is a consequence of the complexity of society, a kind of receptacle if you will. Don’t blame the Eurocrats. The EU is not some fictitious them but us: our companies, our NGOs, our trade unions, our scientists. They are in Brussels due to the enormous amount of legislation required to cope with the complicated social and technological interactions that result when all low hanging fruit has been picked. — Pelle Neroth

Instead of facing this truth (and at times it is admittedly, not pretty), Brexiteer politicians and their tribe have created a simulacrum of a mythical EUSSR, from which they are trying to escape. Paradoxically, we find them voting forthe tentacles they argue strangle them.

Fake news whether domestically generated, the intervention of a Surkovianintelligence agency, or the repacking of age-old conspiratorial tropes, cements the anti-EU, post-modernist nightmare, that Brexiteers have constructed for themselves.

Evidence of Leave politicians woeful misunderstanding of the entity they are fighting to exit has been demonstrated over the course of the preceding three years in ample measure.

Euratom suddenly appeared on the radars of the general public post triggering article 50, yet was barely considered during the Referendum campaign. And what of ENTSO-E? When has there been a public discussion regarding this?

Oh and you ask, what about the other complexities that have arisen over the past 60 years? The ones that silently govern our day to day lives? Freight agreements, data transfer, mobile roaming, satellite infrastructure, joint procurement agreements, gas pipelines, medical supplies, food, financial instruments, tourists, conferences, insurance provision … this list goes on and on. And frighteningly this only scratches the surface.

The progression of treaties and accords have paved the way for a rhizomic system to grow from the bottom up organically, and intersect with the molar top-down implementations oftentimes associated with the treaties.

It’s these bottom-up organic developments that are invisible from merely looking at a set of signed agreements.

Networks are often complex

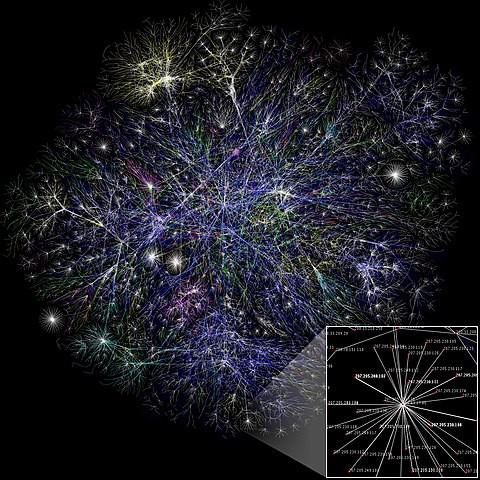

Partial map of the Internet based on the January 15, 2005 data found on opte.org. Wikipedia

For those of you coming from a background in tech, we’ll use a little analogy.

Imagine if society were modelled as one giant switched network. Billions of devices connected through it, sending traffic back and forth. A network administrator may understand the complex cabling and switching equipment in place. But could he be expected to understand every protocol that passes across it, especially at Layer 7?

There are assuredly tools to help and the security analysts in place to monitor the network. But even with the best technology and tools, 100% visibility is improbable. Now scale that network up a billion fold and predict to keep adding nodes Infinitum. Introduce new protocols that none of the networking team understands, or can analyze. Many of these protocols will also be emergent, there’s no standard let alone documentation.

Welcome to how the other layers of Bratton’s Stack have realised themselves in Europe over the course of 60 years and will continue into the future.

The way to build a complex system that works is to build it from very simple systems that work — Kevin Kelly

As Kelly has noted, complex systems that work are often built from simpler building blocks. And this is certainly true of the EU. From the phone call, a florist in England makes to a Dutch flower distributor, to the Irish farmer sending produce to Belfast from Wexford, each act is small and seemingly simple in itself. There are myriad tiny events like this that take place, all predicated on the network existing to allow event X to happen, or item D to get from point N to A. Now scale this up. The complexity is simply impossible to disentangle.

If you imagined globalization and JIT (Just In Time) lead to complexity, you’d be accurate and the EU is an integral part of this process.

What the EU does, for a member state, is eliminate a layer of barriers, allowing the system to become more complex in its interior interconnections, and less complex at the barrier level.

In the EU’s single market (sometimes also called the internal market) people , goods , services , and money can move around the EU as freely as within a single country. Mutual recognition plays a central role in getting rid of barriers to trade. — One market without borders. European Union

You can think of barriers as like firewalls. Within the EU the traffic between nation states is freer flowing, and the firewall rules looser, allowing the complexity to evolve inside the network, rather than at the point of connecting networks, which in the old model was nation-to-nation agreements.

This translates into the real world of not needing to invest effort and time into vast amounts of customs paperwork, visas for travel, roaming charges or work permits.

So now we are presented with a situation where a set of politicians want to yank all the cables from the switches and do a hard reset, disable the wireless access points and start from scratch.

Applications that were running across this network, which our politicians had no concept of are now no longer communicating. All the complex rules for routing traffic, gone!

Our poor network administrators and network users (read civil service, businesses and every person on the street) are now trying to figure out how to rebuild all this, and hope that their applications still run.

And this is basically where the UK finds itself, short on solutions and high on hope.

What next?

This week parliament votes yet again on May’s deal. If it passes, a host of issues will likely come to fore, ones that the public has had little to no visibility on up until now. For example, figuring out what happens with the UK’s relationship with ENTSO-E.

Get used to hearing about all sorts of agencies you never knew existed, and why, after all, they were rather important to the mundane running of day-to-day business.

If we leave without a deal — all bets are off. The headache we will have with May’s deal will turn into a nightmare under none. The gargantuan task of trying to recreate all the network connection we once had, will take years if not decades. The quality of those connections will likely be inferior in many regards. Britain can expect to see its leverage and power projection weakened substantially. The benefits of its soft power tarnished.

And all this because some politicians thought to leave the EU was simple.

Getting out of the EU can be quick and easy — the UK holds most of the cards in any negotiation. — John Redwood MP

Therefore as much as it might hurt these MPs to know, the most complexdecision is to stay, and that would be better for everyone, whether they’d like to admit it or not.

So, perhaps if politicians studied complexity more, they’d propose unfeasible simple options less. Subsequently, events like the EU referendum would be thrown into the dustbin when proposed, which is exactly where they belong.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2VjB775 Tyler Durden