The years from 1815 to 1845 are usually called the Jacksonian Era, but no one person can define the lives of millions. If someone could, the better icon for that age might be Samuel Morse, who invented the most transformative, revolutionary device of the entire century. Even the railroads pale in comparison to Morse’s telegraph.

It was a time of decentralized and dispersed but consequential activities. Innumerable tinkerers worked in shops littered across the land, and every day some new machine hit the market—some contraption to repair clothing, protect your hats, heat your home, cook, clean. Undergirding it all was the revolutionary system of cheap and efficient communications: first the steam presses and cheap newspapers, then telegraphy.

It was America’s first singularity.

In geometry, a singularity is the point on a curve beyond which a fixed viewer can no longer see the curve. Imagine you’re on the street looking at a circular building. There will be points at either end where the shape of the curve prevents you from seeing around the bend.

In astrophysics, black holes are singularities. Their gravitational wells are so strong that literally nothing—not even light—can escape. Approach one closely enough and the singularity will never let go. Gradually, it will pull you into itself, distorting your body, breaking it apart into one long strand of atoms. The black hole turns you into a piece of human spaghetti, sucking you up into its own mass.

In modern computing, the singularity is sometimes spelled with a capital s and takes on the flavor of a religion. The believers think our singularity will be the point at which artificial intelligence becomes indistinguishable from human intelligence. Machines could then improve themselves at dramatically increased rates, the costs of creating more intelligence would fall dramatically, and the explosion of intelligence would change everything.

For most people, the very prospect of a technological singularity is probably terrifying. But Americans have lived through one before, and they not only survived it but emerged to snatch global economic and political leadership from Great Britain. The Jacksonian singularity set the United States on track to become a superpower, the leading edge of global prosperity.

Decisions made during a time of singularity are perhaps the most important decisions human beings ever face, because they remake the world. Americans during the Jacksonian singularity both charted the nation’s course toward a brilliant future and made titanic mistakes along the way. We now find ourselves in a historical situation analogous to theirs, but we do not have the luxury of making their mistakes anymore.

As the pace of change quickened in the 1820s and ’30s, a great threat to entrenched power came from an unlikely source: the post office. Delivery of the mail was far and away the most significant single duty of the national government, and the postal service employed more people than all the other federal bureaucracies combined. Even the farthest-flung places in America had post offices, and access was considered a universal, equal right for all citizens.

Because the post was a government monopoly, it was also an early focal point of conflict over slavery. In the 1830s, abolition societies organized themselves into formal social networks and used the postal system and steam-driven presses to flood Southern mail with abolitionist literature. This activism helped spur the cheap postage movement championed by Lysander Spooner and Barnabas Bates; it also prompted a fierce Southern backlash, complete with mobs burning abolition mail. The more the price of communications fell, the more abolitionists reached out to their fellow beings, touched their hearts, opened their minds, and transformed society.

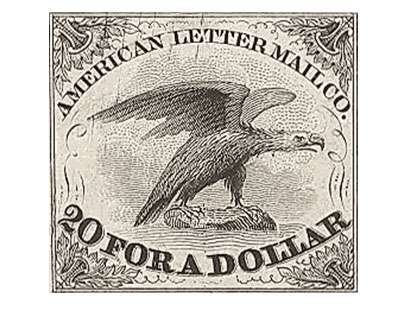

Yet as Spooner understood, slaveholders could easily co-opt the pliant state monopoly, bending it to serve their interests. President Andrew Jackson’s postmaster general, Amos Kendall, set the standard: When Charlestonians mobbed their post office to burn abolitionist literature in 1835, he ignored it and refused to protect equal rights to the mail. Rather than censuring Kendall and Jackson or reforming the postal service, Congress passed the infamous “Gag Rule” to prevent Northern members from considering abolitionist petitions. So Spooner and Bates attempted more radical methods of reform. Spooner established the American Letter Mail Company to directly compete with the postal monopoly, which it did with great success until the government shut it down. Bates diligently lobbied both Whigs and Democrats to lower postage rates in keeping with the British two-cent model. Both men now compete for philatelic recognition as the father of cheap postage in America.

Publishers benefited from privileged prices set by the postal service. Editors across the country exchanged free copies with one another and clipped the choicest articles from distant or significant places to share directly with their audiences. By 1822, more people read newspapers in the United States than anywhere else in the world, though no single paper circulated to more than 4,000 readers. Steam-driven presses and “penny papers” extended the drama even further. In New York City from 1832 to 1836, the circulation of daily papers shot from 18,200 to about 60,000.

Americans became the most literate people in world history. Information flowed across the land as never before and nowhere else on the planet—enough to send anyone reeling.

One randomly selected issue of the New York Daily Plebeian (July 11, 1843) contains advertisements for “marine and fire insurance,” British steamship lines, the Staten Island Ferry, the New York and Erie Railroad, the Housatonic Railroad, the express train to Pittsburgh, and the Daily Express train, which went upstate and then out to Chicago and “the Canadas.” There is an ad for luggage, for a new common school, and for cheap groceries “to suit the times” from Merritt’s Wholesale and Retail Grocery, which offered free delivery to any part of town. There is a very long testimonial praising Sand’s Sarsaparilla and its ability to “throw off…chronic constitutional diseases.” (The copywriter recognizes that “this is sometimes termed quackery” but insists that plenty of “medical profession[als], ministers of the Gospel, officers of justice, and numerous private citizens” swear by it.) If old-timey root beer–like products are not your thing, maybe you’d like to follow in the footsteps of Thomas Parr, “who lived to the unusual and patriarchal age of 182 years…solely attributable to his temperate habits, and…Parr’s Life Pills.” Or you could buy Dr. Hunter’s Red Drop, “warranted to cure in any and all cases of disease of a private nature” (possibly gonorrhea). For my part, I’d rather turn to the next ad and buy some Rock Spring Gin.

After flipping through the news (an uneasy peace between Mexico and Texas), you’ll find that French’s Hotel has expanded. You can follow the shifting values of European currency and then check in on prices to travel with the Northern and Western Emigrant Passage Office. In the “Amusements” section are 50-cent tickets to Niblo’s, which get you a peek at performances by “The astonishing ravel family” of pantomimes and tight rope walkers, including a burlesque show, contortion, and “the Comic Pantomime of Enchantment.” P.T. Barnum’s American Museum features Tom Thumb, “The Prince of all Dwarfs.” At Vauxhall Garden Saloon, you can witness “Chinese Divertisements, with golden balls, rings, plates, spears, &c.,” singing European and “Negro” songs alike, and the “Corpuscular Feats” of Mr. E.H. Conover. If you’re willing to trek across the river to Hoboken, New Jersey, you can visit the Elysian Fields and see more astounding tight rope walking and magic tricks. Perhaps horse racing is more your speed—try the Beacon Course.

There are lease notices for residential and commercial properties, including “a cotton factory of 1500 spindles…in complete working order.” There is an ad for someone named John Brown’s “New Hot Air Cooking Stove”; for a salesman willing to hawk engravings of General Jackson; for “a collection of Wax Figures, large as life, representing distinguished characters.” There is a long set of mortgage sale notices and a section full of legal notices, from the sale of a deceased client’s goods to declarations of debtor insolvency.

One single paper from one single city offers an absolutely bewildering array of information and material wealth. That’s how deeply interconnected New York City’s citizens were by 1843. And in almost every city of appreciable size, you’ll find similarly formatted papers bursting with advertising and news.

Even so, the real singularity was still ahead. Once the telegraph arrived—aided by the ever-growing network of rail lines and steamer companies—cities, states, and regions became connected to one another as if they were neighborhoods in and around Manhattan.

In March 1843, while the Daily Plebian was hawking Parr’s Life Pills, Congress finished mulling over an interesting proposition. Samuel F.B. Morse—a former art professor, failed painter, and amateur technologist—had petitioned it for funds to build a magnetic telegraph from Washington to Baltimore. Packed with development-hungry Whigs and backed by a slaveholding president who fully understood the value of centralized communications, Congress appropriated $30,000.

The first line failed: It went underground but was too poorly insulated. The next line went up on poles. Construction was not yet completed when Morse and his partner, Alfred Vail, sent their first proper message: After Henry Clay won the nomination at the Whig Party’s national convention in Baltimore, Vail sent word to Washington from the Annapolis Junction train station between the two cities. Even without a full connection, the telegraph helped spread the news to the capital an hour and 15 minutes before the usual methods of communication.

If the government had monopolized the telegraph, pro-slavery figures like Andrew Jackson would likely have stayed in command, continuing their policy of censoring abolitionist messages more effectively than ever.

That was May 1, 1844. By May 24, the full line was ready for its first official demonstration. Standing at his machine in the United States Supreme Court, Morse tapped out 21 characters from the Book of Numbers: “what hath god wrought.” About one second later, in Baltimore, Vail’s machine began moving. It recorded the message on paper tape, and the world was immediately and profoundly different. Just like that.

Editorial and news correspondents flocked to Washington and Baltimore to report on Morse’s amazing invention. Probably hoping to inspire as much as inform its audience, the Baltimore Patriot published a long technical description mixed with political warnings. Among the more interesting details is an explanation of how the mechanisms on either end convert the electrical signals into motion and, ultimately, into marks on a continuous paper tape that can be read by the operator or even cyphered for secret communications: “A merchant in New York may write to his correspondent in Philadelphia, without the possibility of its being intelligible to any one except the individual to whom it is addressed. Not even the writer upon the instrument in New York or the attendant in Philadelphia decipher it. With perfect ease the key can be changed every day, or at every 10 words of correspondence. This mode of secret correspondence is more sure and safe than that of ordinary ciphers used for that purpose.”

The Patriot concluded with a call for a state monopoly over the telegraph and government advancement of the new industry: “May this Government foster it with all her care, and give to the Union this bond of her perpetual stability.”

It wasn’t the only voice calling for government control. Just a few days before, the New York Herald had endorsed an open-ended amount of federal support for spreading Morse’s telegraph around the country. “Even amidst the effect of the negligence, bad passions, and folly of both Houses of Congress, we are after all not without some hopes, that such an important project as this will receive some attention,” it editorialized. “The erection of a line of such telegraphs from New York to Washington, [Boston, and New Orleans,] with all the intermediate points, would at once connect the whole of the chief cities of the Union in one magnetic embrace—make them one vast metropolis as it were, producing incalculable benefits in business, government movements, and popular results, and forming a bond of union which nothing could dissever. We do trust that Congress will pass [legislation] on this subject without any delay.”

Some voices warned that if such an important and revolutionary technology were monopolized by the already powerful few, they could control the flow of information and use it to master their fellow human beings. While Morse was still building his first line, the media began warning of a secret cabal of business elites who supposedly already had a working telegraph between Philadelphia and New York. The Philadelphia Gazette reported on this “startling discovery” on June 22, 1844: “No little excitement has just been created in the Stock Board and among the whole circle interested in the Stock business, by the discovery of a telegraphic communication between this city and New York. We remember that the New York correspondent of the North American, several months ago, put the public on its guard against this mode of immediate dispatch practiced by certain parties in both cities. The fact, then doubted, is proved now beyond any question. We need not say that a combination of this sort is entirely at variance with the safe transaction of business by parties not in the secret” (emphases added).

There was indeed an optical telegraph system combining semaphore and cryptography between New York and Philadelphia going back to 1840, and it was reserved for the exclusive use of its businessmen funders. But this was hardly a secret—these networks were the telegraph’s most immediate precursors. Morse’s genius was to replace a long string of semaphore interpreters with cables and electricity, but the skeptics recognized that the line’s owners and operators still functioned as gatekeepers. Many worried that unless the government monopolized the telegraph and built lines to each city as part of the postal service, private actors could usurp control of the nation’s communications for their own benefit and ruthlessly exploit markets or influence elections.

For slaveholders and their allies, of course, the most dangerous private actors were abolitionists, some of whom seemed rich and crazy enough to create a telegraphic version of William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator or Spooner’s American Letter Mail Company. If the government monopolized the telegraph, then pro-slavery figures like Kendall and Jackson would likely stay in command, continuing their censorship policy more effectively than ever. The free flow of information is the greatest enemy a planter ever knew, and Southern laws routinely restricted intellectual and social life, protecting the slave system. It was only reasonable to extend the same practices to new technological frontiers as they opened.

To tame the flow of information, slaveholders would need a government monopoly over the medium, just like Washington’s monopoly over the mail. In the ironically named New Orleans Jeffersonian Republican, the editor warned portentously of “many of the disadvantages and even injuries which may be visited upon the mass of the community if the sole use and control of the Magnetic Telegraph communication be vested in individuals or private companies.” The exclusive right to own and operate a telegraph should “be transferred to the Government, which excludes any monopoly for improper or speculative purposes.” The Republican cited the New York Commercial, which argued that “responsible officials” should manage the industry “in such a manner as to secure the public against the danger of any monopoly of this channel of information.” Telegraphy “in private hands” was unlikely to produce profits or benefit anyone but stock speculators who “could afford to pay larger sums for the nominal monopoly of its use.” Once this happened, the public would surely rise in class revolt and “extinguish it.”

Northern readers of the Commercial saw this kind of class revolt in the 1837 New York City flour riots. Southerners saw it in Nat Turner’s rebellion and the abolition mail campaign of 1835.

The Jacksonian Era was, in fact, the United States’ greatest period of political violence, setting aside the Civil War. Historian David Grimsted studied over 1,200 riots from the 1830s to the 1850s and concluded that they were indeed “a piece of the ongoing process of democratic accommodation, compromise, and uncompromisable tension between groups with different interests.” In the pro-slavery South, this meant a political culture so insistent on protecting white supremacy that “it demanded the cessation of white freedom where it touched that issue: petition, speech, press, assemblage, religion, and—in the 1850s—democratic majoritarianism.”

Fortunately, Congress saw no way to profit from telegraphy and thus passed on the chance to monopolize the industry, to the great benefit of humanity.

As all this social and economic ferment was underway, the locofoco and Young America movements emerged. They developed in tandem in mid-1830s New York City, in the minds and lives of many of the same people, for many of the same purposes. Both movements were partially realized thanks to telegraphy, and they represent the era’s greatest lasting contributions to American life.

Locofocoism was the libertarianism of its day. It began in the Workingman’s Party circles of the late 1820s and early 1830s, and it grew into its own when that Charleston mob burned the abolitionist mail in 1835. After one of New York’s leading young radical editors, William Leggett, began voraciously consuming anti-slavery literature and defending activists’ equal rights to the mail, he was “excommunicated” (his word) from the Democratic Party. Leggett’s work sparked a local rebellion against Tammany Hall and the powers that dominated the state Democratic Party. By taking over their city’s politics, the radicals hoped to force a reformation of the national party and a recommitment to the universal equal rights Leggett defended in the Evening Post. The history of locofocoism is far too detailed for adequate coverage here, but the locofocos did partially retake the Democratic Party, reshaping its policy positions and philosophy. They also inspired two generations of young activists and visionaries in the Young America movement.

Young America began in the private meetings of an informal club called the Tetractys Group led by New York City publisher Evert Duyckinck. The members were publishers, editors, artists, and critics who wanted to create and promote an authentic American national culture distinct from its European antecedents, especially Great Britain. From visual artists like Thomas Cole and Asher Durand to poets like Walt Whitman and novelists like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, Young Americans had already been transforming American culture for a decade before Morse sent his famous messages. They were not all locofocos, but they did imbibe the locofocos’ romantic respect for republicanism, their emphasis on the class nature of U.S. politics and economics, and much of their sense that America’s national destiny depended on strict adherence to liberal moral principles.

Their most serious problem, from a libertarian point of view, was their romantic nationalism, which often reads like naive optimism. Committed locofocos such as Whitman believed politicians such as James K. Polk when he voiced support for free trade, free banking, and free government across the world. Polk was elected quite literally on the strength of about 5,000 locofoco Young American votes in New York, and as soon as he assumed office he betrayed them by rewarding that state’s conservatives and cooking up the slaveholders’ war on Mexico. The anti-slavery Whitman was horrified. He lashed out like Leggett before him, he was fired from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and he emerged from the Mexican War both humbled and radicalized.

The Mexican War divided Young America into two movements: one that supported liberal reform and one that was perfectly willing to make the United States into an empire to advance its political goals. In the 1830s, it was easy to see the groups as allies. When Morse invented the telegraph as part of his own Young American quest to unite the nation’s people into a single great culture, it was at once the opening act in the world’s peaceful new republican destiny and an essential precondition for continental, imperial expansion. Young Americans and locofocos of all stripes could see in the telegraph the fulfillment of their grandest, most astounding dreams, and they ran positively headlong into the unknown future—Mexican War, Civil War, and all.

In Pittsburgh, the radical editor of The Loco-Foco was typical of his peers. Clipping from the New York Herald, he fed his eager campaign-season audience on hearty helpings of jubilant futurism: “We are in the midst of a revolution in society and government on both continents, and one which will produce the most important changes…in the physical and moral world.…The possibility—nay, the practicability of uniting vast communities in one firmly united republic, and the rapid triumph of the social and political system of the United States over all others throughout Europe, are great truths which have for several years past been sinking deep into the minds of civilized man.”

The United States was already “neck and neck” with Great Britain, the Loco-Foco editor wrote, and destined soon to surpass its former overlord. The “extraordinary and wonderful” telegraph now presented the “wonderful spectacle…of a vast continent, as consolidated and united, and possessed as much, nay, in a greater degree, of the means of rapid communication, as the city of New York.” In true Young American language, he continued: “It will tend to bind together with electric force the whole Republic, and by its single agency do more to guard against disunion, and blend into one homogeneous mass, the whole population of the Republic, than all that the most experienced, the most sagacious, and the most patriotic government could accomplish.”

“Every doubt” that constitutional republics could also be continental empires “will now be removed,” the editor exulted. American imperialism now seemed “as natural, justifiable, and safe as the extension of New York to the Harlem river.” Thanks to Morse’s telegraph, “we are indeed on the dawn of a greater era in the history of human progress on this continent than, perhaps, even enthusiasm itself has dreamed.” With the tremendous strength of railroads, steam ships, and vast lands at our backs, “we may, indeed, bid defiance to all enemies.”

The grandest dreamers of all expected that telegraphy would help us conquer death itself. In the late 1840s, one of my favorite 19th century libertarians, a locofoco and Young American named Frances Whipple, was living in Pomfret, Connecticut, when she encountered a man named Samuel Brittan. Brittan was one of the founders of a religion that owed a significant debt to telegraphy: spiritualism, a broad set of mystical beliefs including contact with the dead, the material existence of spiritual beings, the connections between electricity and intelligent life, and other New Agey–sounding things. He quickly converted Whipple to the faith. Through her entire life, she was an advocate for working people’s interests, feminism, abolitionism, and revolutionary republicanism. Once introduced to the new faith, she fell in with the small, swiftly growing, and inordinately influential community of believers and mediums.

Spiritualists practiced séances with the aid of electric batteries and telegraph machines, charging the power of their auras to become “spirit batteries” and communicating with ghosts through “spiritual telegraphy.” For more than two decades, Whipple practiced as a private medium in Rhode Island and California, including at a famous channeling event where a Union colonel, E.D. Baker, purportedly dictated his own funeral oration, which she then delivered herself. (In this way, Baker—as interpreted by Whipple—became the first prominent West Coast politician to advocate emancipation.)

Whipple preached inward reform first and foremost: Technologies like the telegraph might enable us to do great and wonderful things, to aggrandize and exploit our powers like never before, but she felt we must hold ourselves to higher standards than those who have come before us. Rather than use the telegraph to unite a vast and violent empire, she and other feminist mediums argued that we should use the technology to “commune with the wise ones of the ages,” learn from their examples and their grave mistakes, and resolve simply to do whatever we can to be better to each other.

As we enter an age of spiritual machines, with the internet and social media as its substrate and a new Jacksonian populism to match, do we need our own tech-embracing spiritual reform movement? Could individualist libertarianism, with its sacrosanct respect for autonomy and voluntarism, be our answer to the singularity of our times?

Perhaps, but we all know that’s a minority position. Our Jacksonian forebears answered their own existential quandary with expansionist, nationalistic, and fundamentally naive bluster. Pro-slavery Jacksonians saw themselves leading the world into true modernity and used their new powers to expand the Cotton Kingdom to continental proportions. The largely anti-slavery Young Americans—convinced they could bend national power to their own dreams for global republican revolution—diluted their movement with every vote for a status quo politician.

In the end, battles over the mail monopoly translated into a far larger conflict about the national state’s powers and privileges over its component parts. When Abraham Lincoln won the presidency in 1860, Southerners knew what it meant for them: swarms of Republican officeholders invading their ports and taking command of the postal service; abolitionists once again flooding the mail with their messages (at newly reduced rates, thanks to Bates and Spooner); and no power on Earth able to effectively check them. In time, there would even be Republican parties in the Southern states themselves, and Southern newspapers would turn abolitionist. Vast networks of railroads, steam ships, and magnetic telegraphs would transform into the greatest liberating force the world had ever seen. The very thought was intolerable.

For the remnants of locofoco Young America (including Frances Whipple), the Civil War was no mere horror show: It was a grand historical moment for revolution and rebirth, the true fulfillment of our Manifest Destiny. The Jacksonians’ gravest mistake—and they made many—was burying the revolutionary republican tradition in a mountain of nationalistic naiveté. In so doing, they devolved the United States from a grand experiment in self-government into one of history’s more familiar tales: the rise-decline-fall cycle of empire.

Today, the same mistakes might mean the end of civilization itself. But spaghettification is hardly imminent, even if we’re moving dangerously close to that black hole’s gravity well. With as much preparation as we can muster, with serious study of the best examples of how to live freely in turbulent times, with a will to maintain our integrity and a stubborn refusal to make the same mistakes as our ancestors, we just might survive this ride through the historical wormhole without losing our lunch.

from Latest – Reason.com http://bit.ly/2L8wPM8

via IFTTT