Authored by Bryce Coward via Knowledge Leaders Capital blog,

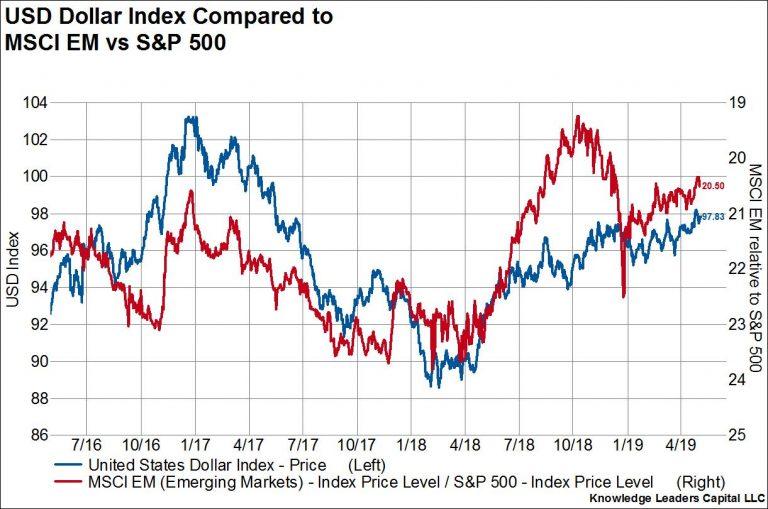

The relationship between the performance of emerging market stocks and the US dollar is one of the tightest macro relationships that exists in investing. As we can see in the first chart, the relative performance of EM stocks vs the S&P 500 is highly negatively correlated with the level of the dollar. That is, when the dollar goes up, EMs underperform US large caps and when the dollar goes down they outperform. It’s like clockwork really. But that observation is nothing new. Indeed, given the recent strength of the dollar we’ve written about it twice in the last two weeks here and here. But it’s also a good time to not just remind readers of the relationship, but also to describe the mechanics of it. That’s what I’ll do here, using the Philippines as our case study. I have no particular bias one way or the other with the Philippines, it’s just one example of many in the EM world for which dollar strength equals trouble, and vice versa.

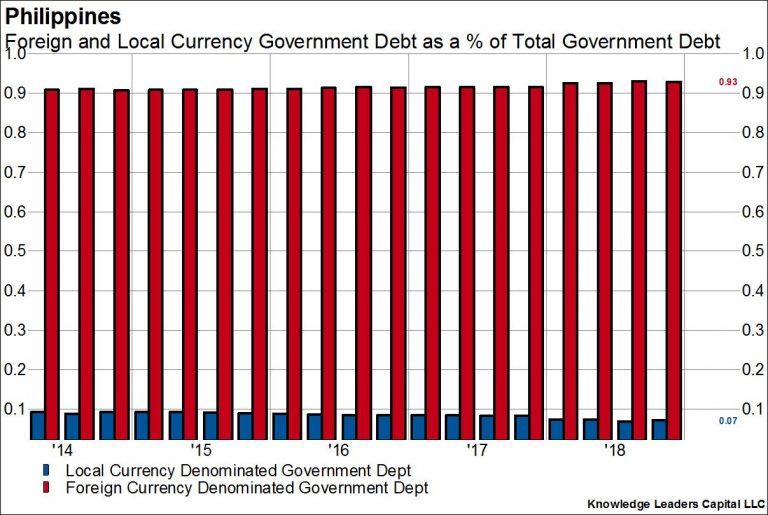

The reason EM stocks and economies tend to struggle in the face of dollar strength is largely due to the quantity of US dollar denominated debt those countries tend to carry as a share of total debt. Why would they carry USD denominated debt instead of local currency denominated debt? The answer is lower interest rates and the ability to place larger amounts of debt. Of course, there are consequences to issuing debt in a currency a country’s central bank cannot print, one of which is that it makes the economy of the issuing country extremely procyclical. That is, economic outcomes are amplified both to the upside and to the downside. This is opposed to many developed market countries which tend to have built in mechanisms in the economy and financial markets that taper cyclicality in both directions.

For example, in the case of a developed market country, when growth and inflation are strong and rising the central bank may raise short-term rates and the bond market will experience higher longer-term rates. With a lag and all else equal, this will tend slow down the economy. When growth and inflation are low and slowing, a developed market central bank may lower short rates or take other measures to boost demand while longer-term rates will naturally fall. With a lag and all else equal, this will provide a cyclical boost to the economy.

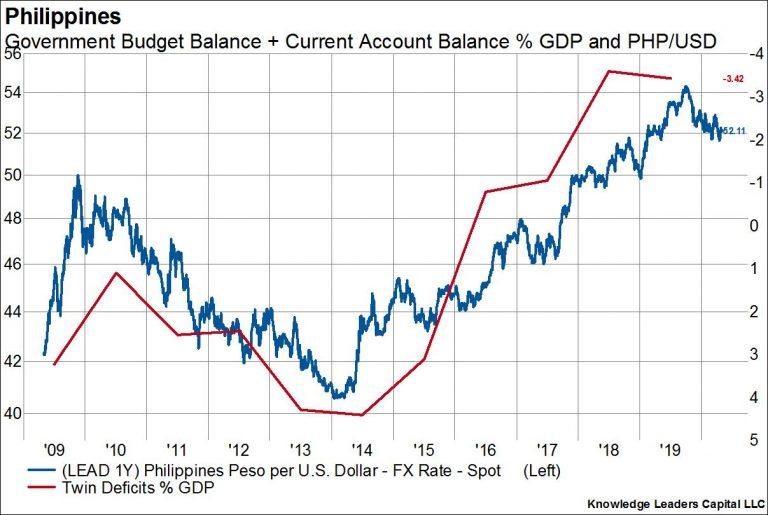

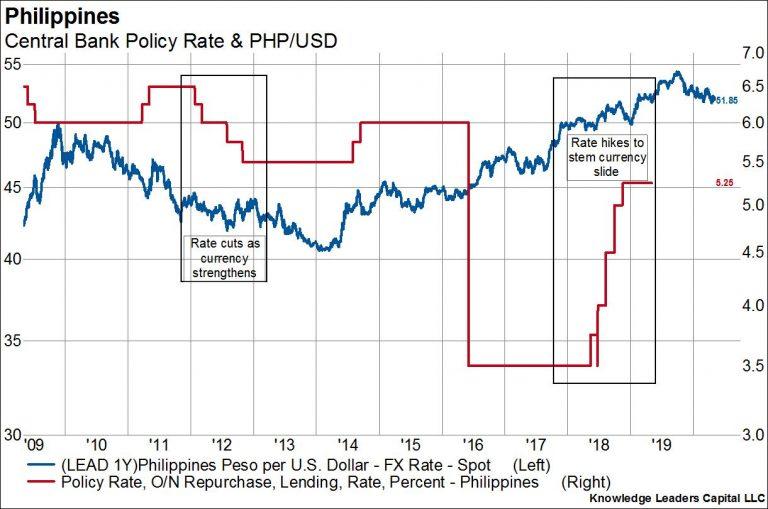

However, when a country’s debt is denominated in a different currency all that changes. Economic booms cause the currency to strengthen and inflation to fall, which allows the central bank to lower policy rates. Because rates are falling and the currency is strengthening, interest and principle payments on foreign currency denominated debt go down, making economic agents feel richer. The government budget balance improves, often moving to surplus and bringing the current account with it. Long-term rates fall in sympathy with short rates, which lower default risks and provides further stimulus. Investment increases, wages rise, growth picks up even more and the currency continues to strengthen. It’s a self reinforcing loop of strength begetting strength.

It’s ugly when it happens in reverse. Weakness in growth causes the currency to fall, which then causes inflation to rise. Higher inflation means the central bank must tighten policy despite the economy turning down. The government surplus turns to deficit, and the need for imported capital causes the current account to turn negative too. The rising short rates and a lower currency causes foreign currency denominated debt payments to increase rapidly. There is a cash flow squeeze, and especially a shortage of US dollars with which to make debt payments. Non-performing loans rise, growth slows more, investment is cut, wages fall, and the currency weakens even more. It’s a self reinforcing loop of weakness begetting weakness. With that, let’s dig into the Philippines example.

This first chart breaks down the local currency and foreign currency denominate government debt as a percent of the total. Local currency debt accounts for only 7% of total debt issuance in the Philippines. The remainder is largely USD denominated debt.

Here we show the twin deficit as a percent of GDP (right axis, inverted) overlaid on the Philippine peso per USD exchange rate (left axis). The exchange rate leads by one year. As the currency rises (blue line going down), the twin deficits improve materially, as they did from 2009-2014. When the currency falls the twin deficits deteriorate as USD debt payments become more onerous.

Currency rises and falls bring inflation with it. When the currency strengthens (blue line going down) inflation tends to fall, and vice versa.

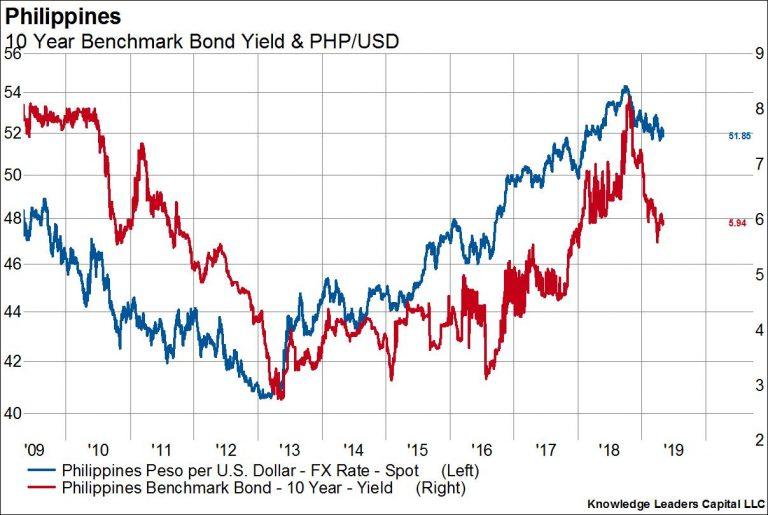

The inflationary dynamics cause the central bank to act. In the case of the Philippines, this meant rate cuts from 2011-2012 as the currency was strengthening and rate hikes in 2018 as the currency was falling precipitously. In this case, currency moves led central bank action by about a year.

Of course, economic strength caused by the rising currency pushes down long-term bond rates credit risk abates. The opposite is true when the currency weakens.

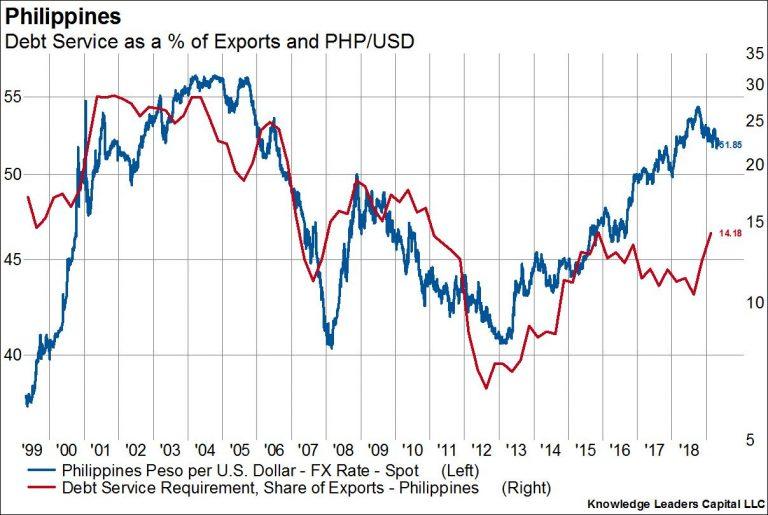

When the currency is falling, debt service gets harder. The government and companies must come up with US dollars with which to pay the lenders. The way they earn those US dollars is through exports. As the currency falls, a larger and larger portion of the US dollars the country earns through exports get used in debt repayment. In other words, US dollar liquidity tightens dramatically, which only reinforces the currency weakness. Of course, the opposite is also true when the currency is strong.

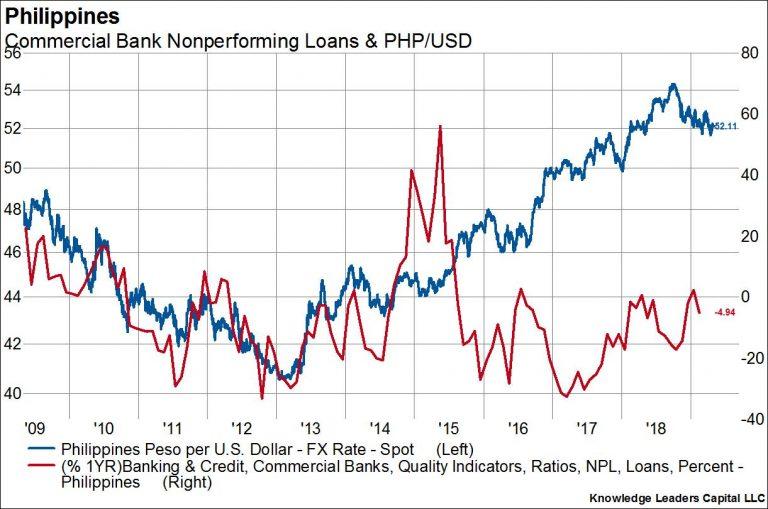

Non-performing loans are highly correlated to changes in the exchange rate. A rising local currency means debt payments are easier to meet and NPLs fall. A falling currency means debt payments are much more difficult to meet and NPLs rise.

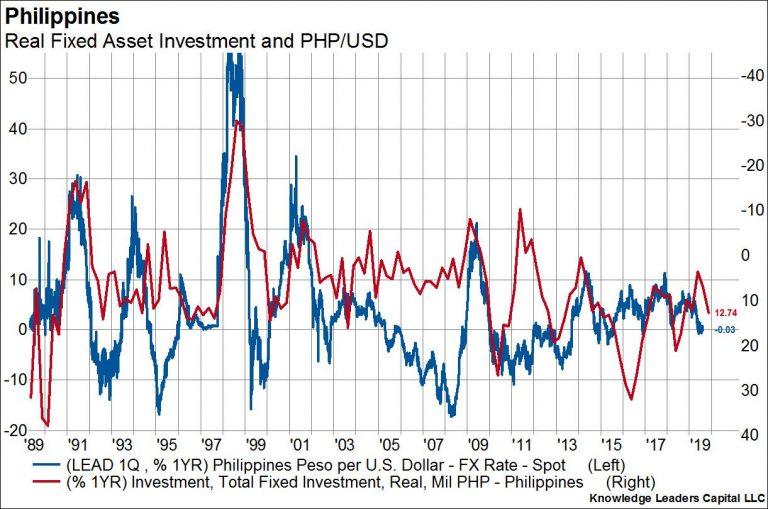

If companies are flush because their debt obligations are lower, they are more inclined to invest, and vice versa. Dramatic currency strength or weakness feeds right into the real economy through investment.

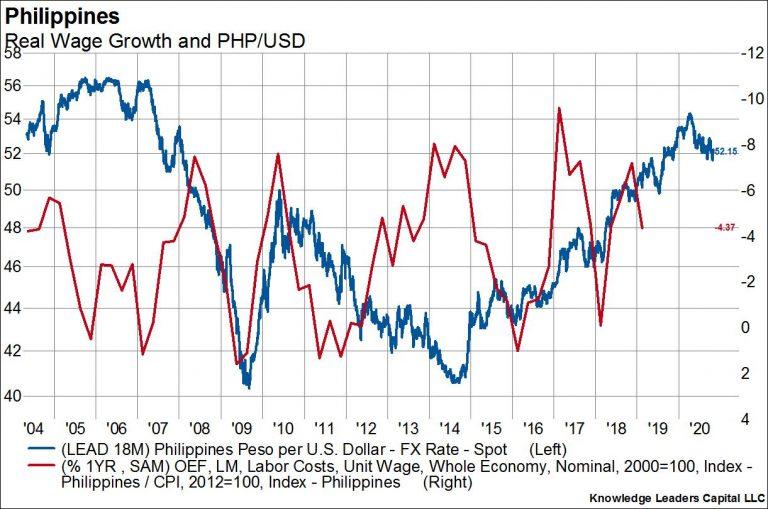

While unemployment may or may not be affected by the currency, real wages (wage growth after inflation) do tend to be highly correlated to the currency, with a lag of 18-24 months. Higher wages obviously raise consumption and reinforce the growth while falling wages reinforce the downturn.

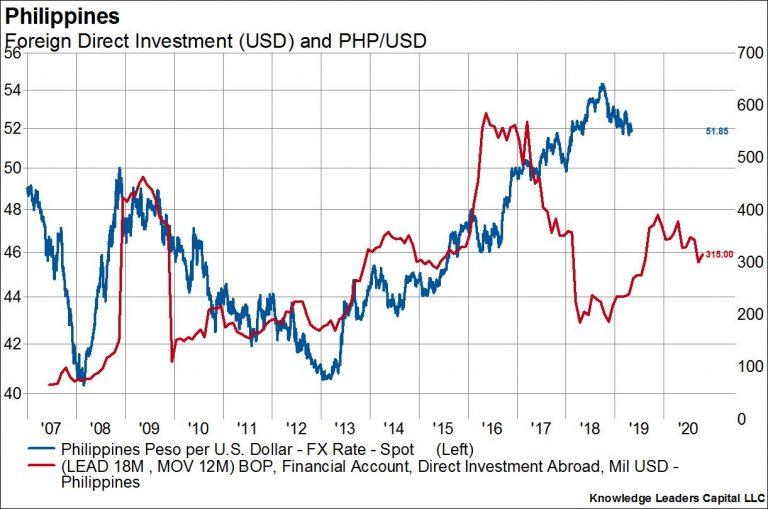

The cycle ends when the currency gets to such extreme levels that foreigners add to or subtract from foreign direct investment. When the currency is so low that the future ROIC of foreign direct investment is exceedingly high, dollars will start to flow back into the country. This was 2009 and 2016 in the case of the Philippines. Foreign investors were rather tepid from 2010-2013 and then again in 2018, but may be coming back in. Foreign direct investment flows lead currency moves by 12-24 months.

As readers can see, there happen to be logical, almost mechanical, relationships between EM currencies and the economy that reinforce either growth or a slowdown. In the end, it all comes back to debt, and the propensity of EMs to issue debt denominated in currency other than the one they print. The result for investors is a very predictable EM relative performance pattern that is directly tied to the US dollar.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2DXPLav Tyler Durden