Last month, we reported that Boeing slashed production of the troubled 737 Max from 52 to 42 airplanes per month. Now, a new report from the Financial Times shows how production cuts are set to drive some of the company’s suppliers into financial hardship.

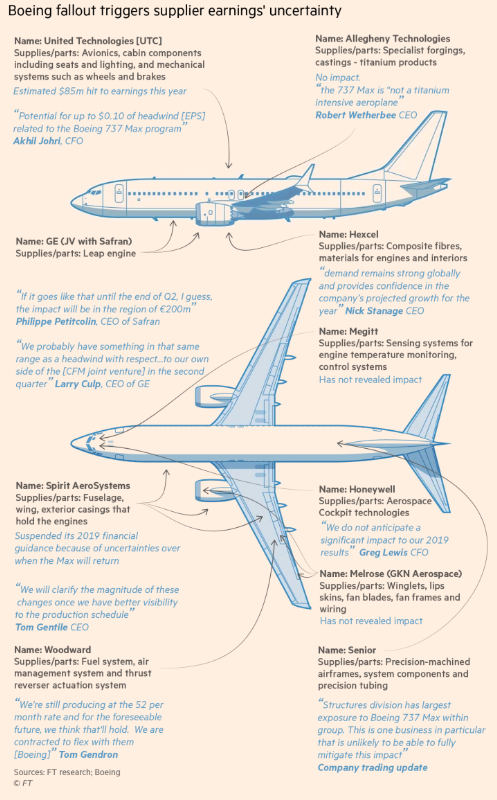

Spirit AeroSystems, a 737 Max supplier that produces 70% of the plane’s aerostructure, pulled its 2019 financial guidance, warning that past guidance is no longer valid because of the production cuts and no visible timeframe of when the planes will be back in the air.

Financial Times notes that Spirit AeroSystems is for right now, insulated from the cuts because it worked out a deal with Boeing to continue producing at the old rate (52 planes). The supplier is quickly building inventory at its facilities. They’re only a few of the suppliers that are producing at the old rate, while others have transitioned to 42 per month, a 20% decline from the old rate.

Safran, a French multinational aircraft engine company with a joint venture with General Electric that produces engines for the Max, expects a $224 million hit in the next quarter.

GE’s new chief executive Henry Culp recently confirmed a similar view: “We probably have something in that same range as a headwind with respect . . . to our own side of the [CFM joint venture] in the second quarter.”

Woodward, a Max supplier that produces avionics, seats and engine covers, said its production hadn’t been affected by the Max slowdown, though it said the company holds no contractual agreements with Boeing that guarantees a specific production rate. “We are contracted to flex with them,” chief executive Thomas Gendron told investors on an earnings call. Gendron said like many other suppliers in the Max supply chain, the downtime has been used to catch up on previous production delays.

He warned about “uncertainties and some risks in the second half” due to limited guidance from Boeing about production and ungrounding of the planes.

We reported that Boeing plans to coordinate with customers and suppliers to blunt the financial impact of the slowdown, and for now it doesn’t plan to lay off workers from the Max program.

“When the Max returns to the skies, we’ve promised our airline customers and their passengers and crews that it will be as safe as any airplane ever to fly,” Boeing Chief Executive Officer Dennis Muilenburg said in an April statement.

Boeing had planned to hike output of the Max, a workhorse for budget carriers, about 10% by midyear, to meet the backlogs.

As we noted, suppliers who provide the 600,000 parts needed for each plane had already started moving toward a 57-jet monthly pace under a carefully orchestrated schedule set in place long before the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines disasters, and it seems those suppliers could be hit with production declines in 2Q or possibly sometime in the 2H.

The bigger question, as we previously detailed, is what effect a 20% cut to Boeing’s production will have on US GDP in Q2?

…a recessionary catalyst may be the fiasco involving the Max, which according to JPM economist Michael Feroli, could begin impacting the economic dataflow. According to the biggest US bank, the issues affecting the Max should have no short-run impact on GDP, as the production of this airplane is continuing, but will affect the composition of GDP, implying more growth in inventories and less growth of business investment and gross exports.

However, if the issues are not resolved in a timely manner and production of the Max needs to be halted for an extended period of time, it would send many of Boeing’s suppliers into financial stress and could even shave off about 0.15% off the level of GDP, or about 0.6%-point off the quarterly annualized growth rate of GDP in the quarter in which production is stopped.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2H6KT3d Tyler Durden