Reckless global monetary policy, led by the Federal Reserve, has literally forced the smart money to try and think stupid in order to make money. While fund managers are calling it “a new strategy”, we can’t help but see it for what it really is: anything but a vote of confidence for the central banking status quo.

For instance, despite running a $500 million hedge fund, manager Tom Zhou spends most of his time trying to “think like a novice investor,” according to Bloomberg. He has has degrees in civil engineering, economics and finance but, for him, the key to figuring out the $6.6 trillion Chinese stock market isn’t higher education, it’s dumbing things down.

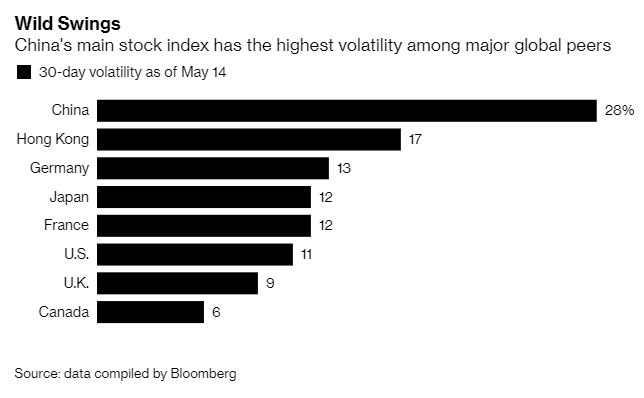

Since the Chinese market is 80% driven by mom and pop investors, quants and fund managers are stuck trying to literally “predict where the dumb money is heading”. It’s a tougher task than some might think, especially because of China’s market volatility and price swings that often defy logic.

So now quants comb through social media posts and use AI to try and anticipate how 147 million retail investors will collectively act. They perpetuate the self-fulfilling prophecy of technical indicators, trying to predict when investors will use them as cues to buy and sell. And they’re spending tons of money buying data from companies like Tencent to gauge sentiment.

As the country is now part of the MSCI Global Indexes, the “strategy” makes light of how global participants in the Chinese market may need to tailor their thinking to adapt to different market psychologies.

Zheng Xu, a former portfolio manager at Millennium Partners said: “In the U.S., quants are trying to make money off other institutional investors with complex models or automated transactions at lightening speed, but in China many strategies don’t work well and quants’ arch rivals are retail investors. Understanding retail investors’ behavior and sentiment is extremely valuable here.’’

Some quants detailed how they have been modeling the impact of retail investors on China’s stock market. For instance, Chinese traders have a tendency to lock-in profits more quickly than their peers, Zhou said. As it relates to an investment thesis, this means that short-term price reversal factors tend to perform better in China than momentum factors.

High Flyer Quant, a firm that manages $870 million in Hangzhou, uses AI to anticipate as many as two days in advance when technical indicators will prompt investors to buy or sell. BlackRock tracks changes in sentiment by analyzing about 100,000 chat room posts a day on websites like Eastmoney.com and Xueqiu.com. The firm tailors its buys to names that attract growing attention in these rooms and sells stocks that fall out of favor.

Wang Pei, chief executive officer of Shenzhen-based Focus Technology Ltd., said his fund netted an additional 7% to 8% annually by incorporating data on the most viewed stocks in trading apps owned by Tencent and Hithink RoyalFlush Information Network Co. This strategy failed to work in 2015, as competitors adopted the same strategy.

China’s unique rules can sometimes make it frustrating for quants, too. For instance, abiding by a rule that prevents investors from buying and selling the same shares in a single day can make some high-frequency trading tactics difficult. Additionally, the country’s censorship of social media is a challenge for those looking to monitor it for investor sentiment.

The median return for funds linked to China’s CSI 300 Index beat the benchmark by 3.63% in 2018. In Q1 of this year, funds underperformed the benchmark by 3.22%.

And other international shops, like Boston-based PanAgora Asset Management Inc., are experimenting with new models based on trying to find these outsized returns.

Mike Chen, who works for PanAgora, developed a model to identify the slang Chinese retail investors use on online message boards. His interest was piqued after he noticed some “strange” moves in Chinese stocks after the 2016 election:

He became interested in the challenge in part because of some quirky moves in Chinese stocks in the wake of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. When the result became clear, a listed Chinese company whose name sounds like “Trump Wins Big’’ in Mandarin surged, while a firm that sounds like “Aunt Hillary’’ slumped.

Chen concluded: “There are a lot of inefficiencies, and many of these are driven by retail investors. You want to understand what they think, but you can’t do it through the traditional financial statements.’’

We can’t help but think that’s a nice way of saying: “The financials don’t matter anymore and, even if they did, you’d be too stupid to read them.”

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2EkPAWI Tyler Durden