Over the past year, Western media organizations have published a non-stop stream of reports about “Operation Cloudhopper”: The Chinese government’s clandestine program to spy on and siphon economic secrets from some of the world’s largest tech companies.

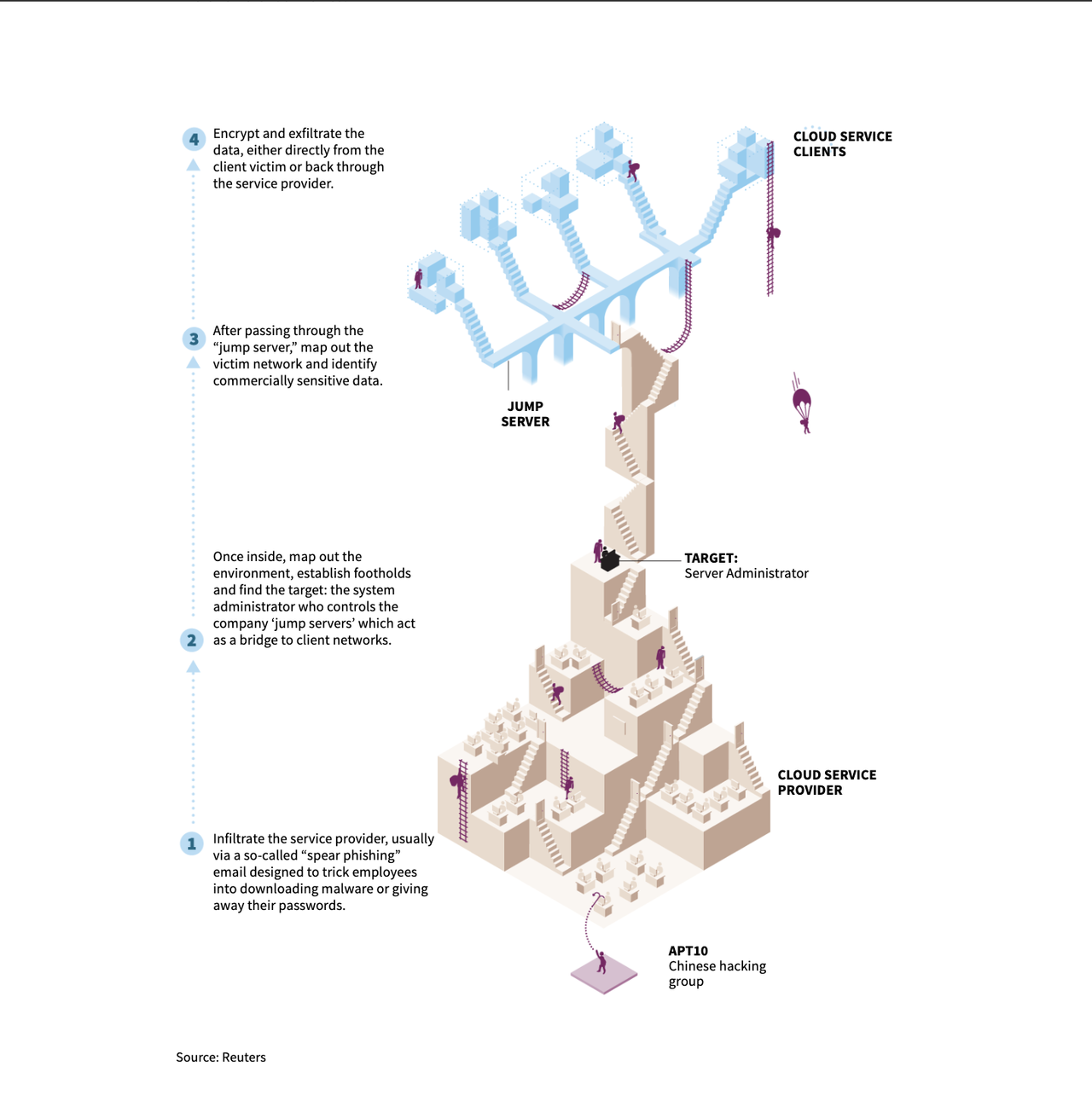

We have shared some details of the program before: China’s Ministry of State Security has worked with a shadowy group of hackers called ‘Advanced Persistent Threat’ 10 to infiltrate American and European enterprise tech firms using a very consistent MO: Hackers would infiltrate the cloud computing networks of ‘managed service providers’, then ‘hop’ from network to network’, gaining entree to the networks of these firms’ clients. Back in December, the US named some of the hackers suspected of working with APT10, and was backed up by Germany, New Zealand, Canada, Britain, Australia and other allies all issued statements.

Notably, the Chinese cyberespionage campaign continued even after Beijing and the Obama Administration agreed to a pact to cease all cyberespionage activities.

But as devastating as these attacks have been, the details have been kept under wraps, as corporate victims have pushed for their privacy to be protected. But for the first time since the US indicted the two suspected APT members, a sweeping Reuters investigation has laid out details of attacks, many of which have been previously reported, but not in quite as much depth.

An investigation by Reuters found that “Cloud Hopper” impacted six additional firms aside from IBM and HPE, which it had previously reported. These included at least five of the world’s 10 largest tech service firms. In addition to HPE and IBM, the hacks emanated out to those firms’ clients, including Swedish telecoms firm Ericsson, and a handful of Japanese fims. Ultimately, industrial and commercial secrets were stolen.

The hacking campaign, known as “Cloud Hopper,” was the subject of a U.S. indictment in December that accused two Chinese nationals of identity theft and fraud. Prosecutors described an elaborate operation that victimized multiple Western companies but stopped short of naming them. A Reuters report at the time identified two: Hewlett Packard Enterprise and IBM.

Yet the campaign ensnared at least six more major technology firms, touching five of the world’s 10 biggest tech service providers.

Also compromised by Cloud Hopper, Reuters has found: Fujitsu, Tata Consultancy Services, NTT Data, Dimension Data, Computer Sciences Corporation and DXC Technology. HPE spun-off its services arm in a merger with Computer Sciences Corporation in 2017 to create DXC.

Waves of hacking victims emanate from those six plus HPE and IBM: their clients. Ericsson, which competes with Chinese firms in the strategically critical mobile telecoms business, is one. Others include travel reservation system Sabre, the American leader in managing plane bookings, and the largest shipbuilder for the U.S. Navy, Huntington Ingalls Industries, which builds America’s nuclear submarines at a Virginia shipyard.

“This was the theft of industrial or commercial secrets for the purpose of advancing an economy,” said former Australian National Cyber Security Adviser Alastair MacGibbon. “The lifeblood of a company.”

Over the course of its reporting, Reuters interviewed 30 people involved in the “Cloud Hopper” investigations, including government officials, company insiders and private security contractors. One of the most stunning aspects of the investigation was how persistent the hackers were. Even after their code was purged from the network, APT managed to find its way back in.

Also incredible: How the security breaches went unnoticed, sometimes for years.

For security staff at Hewlett Packard Enterprise, the Ericsson situation was just one dark cloud in a gathering storm, according to internal documents and 10 people with knowledge of the matter.

For years, the company’s predecessor, technology giant Hewlett Packard, didn’t even know it had been hacked. It first found malicious code stored on a company server in 2012. The company called in outside experts, who found infections dating to at least January 2010.

Hewlett Packard security staff fought back, tracking the intruders, shoring up defenses and executing a carefully planned expulsion to simultaneously knock out all of the hackers’ known footholds.

But the attackers returned, beginning a cycle that continued for at least five years.

Throughout the investigation, the Chinese hackers showed their American peers how woefully ill-equipped they were. Not only did the hackers stay one step ahead of the investigators tracking them, but they littered their code with expletives and taunts.

The intruders stayed a step ahead. They would grab reams of data before planned eviction efforts by HP engineers. Repeatedly, they took whole directories of credentials, a brazen act netting them the ability to impersonate hundreds of employees.

The hackers knew exactly where to retrieve the most sensitive data and littered their code with expletives and taunts. One hacking tool contained the message “FUCK ANY AV” – referencing their victims’ reliance on anti-virus software. The name of a malicious domain used in the wider campaign appeared to mock U.S. intelligence: “nsa.mefound.com.”

Ultimately, it’s impossible to say how many of HP’s customers were impacted by “Cloud Hopper”. Though investigators were able to envision at least one “nightmare scenario” involving an HP client: Sabre Corp., a travel-reservation company and HP client, might become vulnerable to Chinese infiltration. If APT and the MSS could gain access to Sabre’s systems, they could easily track the travel patterns of American corporate executives and other VIPs, exposing them to in-person surveillance and bugging.

The HPE operation had hundreds of customers. Armed with stolen corporate credentials, the attackers could do almost anything the service providers could. Many of the compromised machines served multiple HPE customers, documents show.

One nightmare situation involved client Sabre Corp, which provides reservation systems for tens of thousands of hotels around the world. It also has a comprehensive system for booking air travel, working with hundreds of airlines and 1,500 airports.

A thorough penetration at Sabre could have exposed a goldmine of information, investigators said, if China was able to track where corporate executives or U.S. government officials were traveling. That would open the door to in-person approaches, physical surveillance or attempts at installing digital tracking tools on their devices.

In 2015, investigators found that at least four HP machines dedicated to Sabre were tunneling large amounts of data to an external server. The Sabre breach was long-running and intractable, said two former HPE employees.

Via the breach at HP, APT and the MSS also gained entree to the American defense industry by accessing the server of Huntington Ingalls, a company that builds nuclear powered submarines.

In early 2017, HPE analysts saw evidence that Huntington Ingalls Industries, a significant client and the largest U.S. military shipbuilder, had been penetrated by the Chinese hackers, two sources said.

Computer systems owned by a subsidiary of Huntington Ingalls were connecting to a foreign server controlled by APT10.

In Sweden, Huawei rival Ericcson was a persistent target of MSS, though the company often couldn’t tell what, exactly, the hackers were after.

Like many Cloud Hopper victims, Ericsson could not always tell what data was being targeted. Sometimes, the attackers appeared to seek out project management information, such as schedules and timeframes. Another time they went after product manuals, some of which were already publicly available.

In what has become a pattern for reports about China’s cyberespionage, the Reuters expose was published as President Trump prepares to depart for Osaka for the G-20 summit, where he’s scheduled to meet with President Xi. Under Trump, the DoJ has stepped up its efforts to punish China and individuals spies for their cyberespionage activity. Whether Trump stands his ground on cyberespionage is only one factor here. Even if Beijing grants assurances that it will stop, how can the US be sure that it’s not simply lip service like that paid to the Obama administration?

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2JmpSTF Tyler Durden