Every six month or so, the Bank of International Settlements, also known as the central banks’ central bank, publishes some dire warning about the increasingly precarious state of the global financial system – largely as a result of an unprecedented monetary experiment that is now pushing on a string – and every six months or so the world’s most important central bankers congregate on 18th floor of the circular BIS tower in Basel where they decide to ignore all the warnings and double-down on policies that haven’t worked in a decade, with the expectation that they will work this time (or at least make the world’s richest even richer, while destroying the middle class).

Well, today is one of those days, because at midnight on June 30, the BIS published it Annual Economic Report for the year 2019, and of course, this report too and the speech delivered alongside the Annual General Meeting in Basel by Agustin Carstens, will be summarily ignored by those who matter, until the next financial crisis strikes and everyone is shocked how there were no signals indicating the arrival of what will soon be the greatest financial catastrophe in world history.

Of course, the BIS won’t make any such dire predictions – the last thing it needs is to be accused of sowing the panic that unleashes a crisis – it will however warn that after a failed attempt by central banks to renormalize monetary policy, governments must step in to stimulate their economies and fix policy imbalances that have forced central banks to use up most of their firepower: “The continuation of easy monetary conditions can support the economy, but make normalization more difficult, in particular through the impact on debt and the financial system,” the BIS warned.

As a result of central banks going all in again in what some have dubbed the last rate to the bottom, “the narrow normalization path has become narrower.”

If that wasn’t enough, in his speech, Carstens explicitly brought attention to this critical issue:

While the near-term outlook is still good, there are many vulnerabilities further out. For the global economy to remain on course towards clear skies, other policies need to play a bigger role and policymakers must take a longer-term perspective. In particular, a better mix is required between monetary policy, fiscal policy, macroprudential measures and structural reforms. And navigating the way to clear skies also means balancing speed with stability as well as conserving some fuel to cope with possible headwinds. This matters all the more given the many uncertainties and risks we face today.

The above excerpt comes from the speech by BIS general manager Agustin Carstens who urge politicians to “ignite all engines” to overcome a global soft patch, which can no longer be punted on central banks in hopes that lower rates will stimulate the global economy for one simple reason: with rates at all time lows, there is virtually nothing left to cut. Worse, rates are now so low that – at least the BIS admits – banks are now suffering as a result of monetary policy:

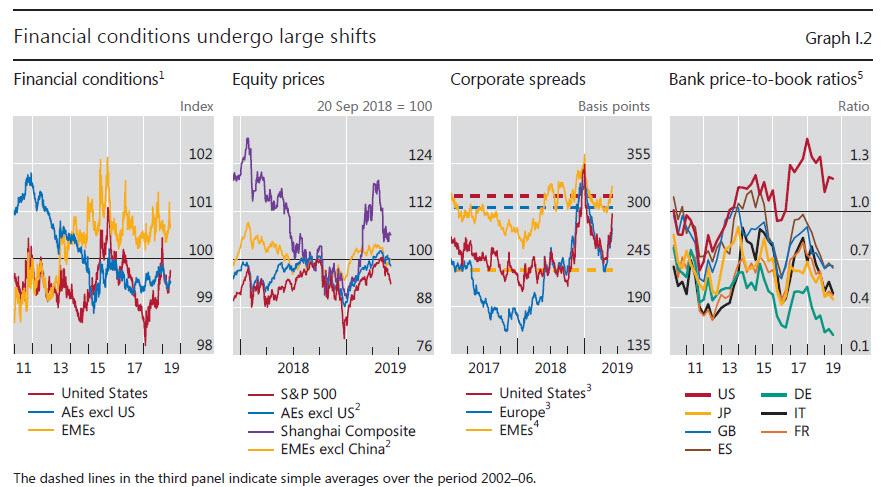

Price stability – central banks’ key mandate – naturally reinforces the case for maintaining policy accommodation, or easing further, as inflation is below target. Closely related is the need to bring inflation expectations back towards target. This approach is even more compelling if financial markets look fragile, as they appeared late last year, and could impact the economy adversely. The greater the uncertainty about conditions in the financial system and the macro economy, the stronger the case for a more gradual strategy.

At the same time, the gains from such a strategy could be associated with costs and less room for policy manoeuvre in the future. The possible costs arise mainly through financial channels. The historically low-for-long interest rates tend to compress banks’ margins, lower profits and hence reduce banks’ ability to build up capital, essential for a productive economy.

And here is the #timestamp for you warning, so that the next time banks complain that nobody could have possibly seen the catastrophe coming, one can counter that their very supervisor warned them (and again, and again), of what was coming:

Very easy financial conditions may boost growth in the near term but may further build up vulnerabilities. And persistently low rates may undermine efficient resource allocation and productivity

Under such circumstances, the BIS warns, the future room for policy manoeuvre could shrink for two reasons:

- To the extent that normalization does not end up weakening economic activity, a more gradual approach would reduce policy space directly.

- More subtly, the side effects of very accommodative policies might themselves sap the economy’s ability to withstand higher rates, making any normalisation harder.

Meanwhile, since monetary policy has been “unconventional” for more than a decade, the BIS also points out that in addition to the conventional recent bogeymen of trade protectionism and China’s deleveraging, as a result of the prolonged period of easy financial conditions “many vulnerabilities have built up and could throw the global economy off course,” i.e. there are now bubbles everywhere, including household debt, the leveraged loan market, and emerging markets feasting on USD-denominated debt:

- One such vulnerability is high household debt in many advanced economies, especially those not directly affected by the Great Financial Crisis. These historically high debt levels limit the scope for households to drive economic activity.

- Another vulnerability is clear signs of overheating in the corporate sector in a number of advanced countries. Following high growth, the leveraged loan market is now some USD 3 trillion in size, comparable to the collateralised debt obligations that amplified the subprime crisis. Structured products such as collateralised loan obligations (CLOs) have surged. Credit standards have been declining as investors have searched for yield. Should the leveraged loans sector deteriorate, the economic impact could be amplified through the banking system and other parts of the financial system that hold leveraged loans and CLOs. There could be sharp price adjustments and funding tensions. These risks should be seen in the broader context of the longer-term deterioration in credit quality and the generally high corporate leverage in many advanced economies.

- High levels of debt also point to vulnerabilities in a number of emerging market economies (EMEs). In some cases, these are in the household sector. Most often, they are in the corporate sector, not least as foreign currency debt has expanded strongly since the crisis. The current vulnerabilities reflect in part spillovers from prolonged accommodative monetary policies in advanced economies, as EMEs are especially vulnerable to capital flow reversals and exchange rate fluctuations.

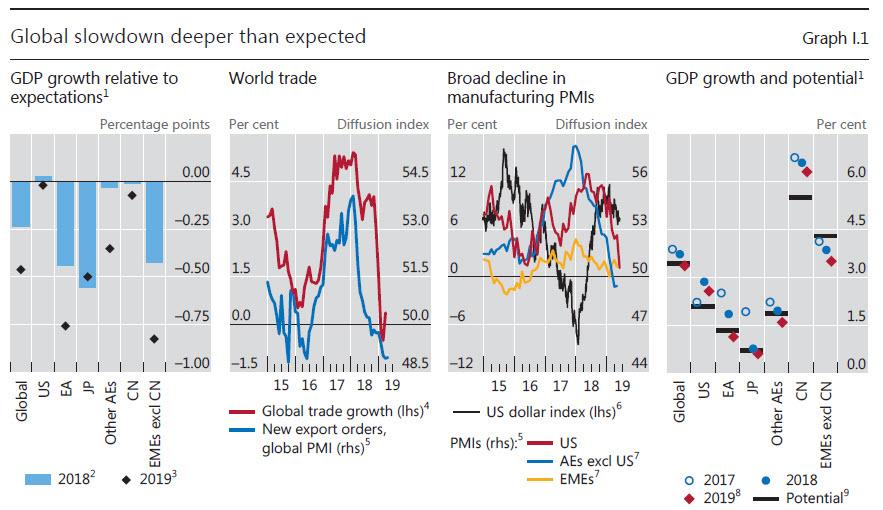

Meanwhile, even as central bank ammunition has dwindled to almost nothing, global growth is slowing: “If anything, the slowdown appears to be worsening and spreading since the Report went to press. There are signs of weaker consumption and investment.”

Not only that, but as the BIS also warns, significant near-term risks exist. Notably, the trade tensions that contributed to the slowdown could flare up again, even as financial conditions are undergoing major shifts.

Other threats include political economy risks in some countries. China’s deleveraging is not complete. And if past experience is anything to go by, the contraction phase of the financial cycles under way in many countries is likely to act as a headwind for global growth.

The BIS’ bottom line, with monetary policy now helpless, structural reforms are vital and fard as it is politically, it is essential to revive the flagging efforts to implement structural policies designed to boost growth. These days, policies to adapt economies to rapid technological and other structural changes are especially important.

Clear skies may be over the horizon, but we have yet to cross it. Many risks and vulnerabilities exist, and political uncertainty is high. The course towards normalisation has called for some deviations. A sustainable flight path requires the long-overdue full engagement of all four policy engines, rather than short-term turbo charges. By taking a longer view, one can better balance the needs of today with the needs of tomorrow.

The punchline: “hard as it is politically, it is essential to revive the flagging efforts to implement policies designed to boost growth… Monetary policy can no longer be the main engine.”

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2JgyvPl Tyler Durden