Authored by Binoy Kampmark via Oriental Review,

“The founder of Netscape said software is going to eat the world.”

Tristan Harris, Centre for Humane Technology, June 25, 2019

Monsters and titans share the stage of mythology across cultures as the necessary realisations of the human imagination. From stone cave to urban dwelling, the theme is unremitting; kept in the imagination, such creatures perform, innocently enough, benign functions. The catch here is the human tendency to realise such creatures. They take the form of social engineering and utopia. Folly bound, such projects and ventures wind up corrupting and degrading. The monster is born, and the awful truth comes to the fore: the concentration camp, the surveillance state, newspeak, the armies of censorship.

The technology giants of the current era are the modern utopians, indulging human hunger and interests by shaping them. One company gives us the archetype. It is Google, which has the unusual distinction of being both noun and verb, entity and action. Google’s power is disproportionately vast, a creepy sprawl that cherishes transparency while lacking it, and treasuring information while regulating its reach. It is also an entity that has gone beyond being a mere repository of searches and data, an attempt to induce behavioural change on the part of users.

Google always gives the impression that its users are in the lead, autonomous, independent in a verdant land of digital frolicking. The idea that the company itself fosters such change, teasing out alterations in behaviour, is placed to one side. There are no Svengalis in Googleland, because we are all free. Free, but needing assistance amidst chaos and “multitasking”.

People have what the company calls “micro-moments”, those, as behavioural economist Dan Ariely describes as “on-the-go mobile moments” where decisions are reached by a user while engaged, simultaneously, in a range of tasks: hotels to book, travel choices to make, work schedules to fulfil. While Ariely is writing more broadly from the perspective of the ubiquitous digital marketer, the language is pure Googleleese, smacking of part persuasion and part imposition. “Want to develop a strategy to shape your consumer decisions?” asks Google. “Start by understanding the key micro-moments in their journey.” Understand them; feed their mind; hold their hand.

The addiction to Google produces what can no longer be seen as retarding, but fostering. A generation is growing up without a hard copy research library, a ready-to-hand list of classics, and the means to search through records without resorting to those damnable digital keys. Debates are bound to be had (some already pollute the digital space) about whether this is necessarily a condition to lament. Embrace digital amnesia! To Google is to exist.

What is undeniable is that the means to find information – instantaneous, glut-filled, desperately quick – has created users who inhabit a space that guides their thinking, pre-empting, cajoling and adjusting. One form of literacy, we might kindly say, is being supplanted by another: the Google imbecile is upon us.

Given the nature of such effects, it is little wonder that politicians find Google threatening to their mouldy and rusted on craft. The politician’s preserve is sound – or unsound – communication; success at the next election is dependent upon the idea that the electors understand, and approve, what has been relayed to them (whether that material is factual, or not, a lie or otherwise, is beside the point: the politician yearns to convince in order to win).

The old search engine titan supplies something of a snag in this regard. On the one hand, it offers the political classes the means to reach a global audience, an avenue to screech and promote the next hair-brained scheme that comes into the mind of the political apparat. But what if the message stymies on the way, finding delays in the means of what is called “search engine optimisation”? Is Google to blame, or bog standard ordinariness on the part of the politician?

US politicians think they have an answer. Only they are permitted control of the narrative, and disseminating the lie. Of late they have been trying to sketch out a path they are not used to: regulating industries once hailed as sentinels of freedom, promoters of liberty. Their complaints tend to lack consistency. On the one hand, they find various Google algorithms problematic (preference for alt-right sites, conspiratorial gruel as damaging), but their slant is wonky and skewed. Had these algorithms been driving favourable search terms (conformist, steady, unquestioning, anti-Trump), the matter would be a non-starter. Our message, they would say, is getting out there.

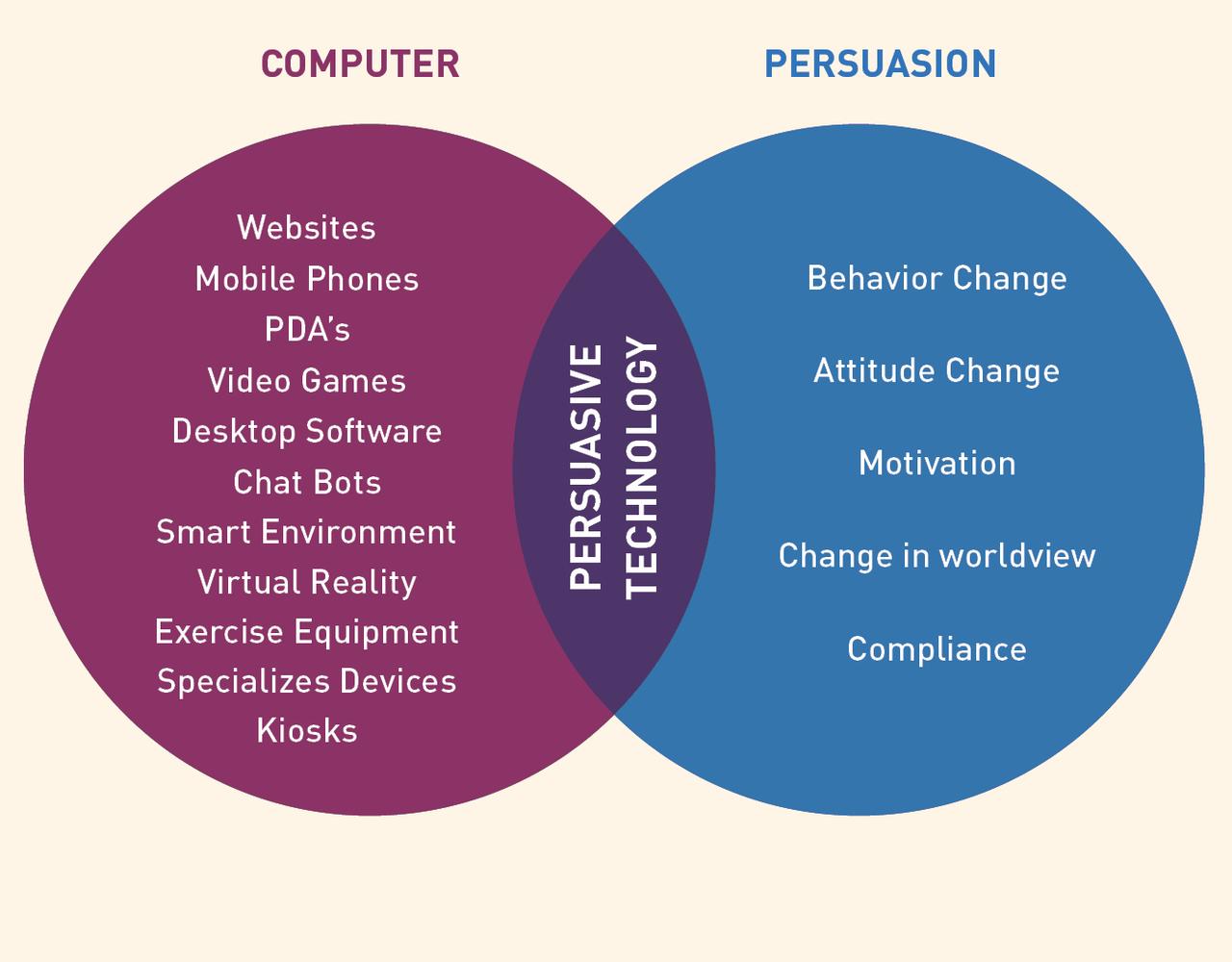

This week, the US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation tried to make sense, in rather accusing fashion, of “persuasive technology”. Nanette Byrnes furnishes us with a definition: “the idea that computers, mobile phones, websites, and other technologies could be designed to influence people’s behaviour and even attitudes”. The Pope does remain resolutely Catholic.

The committee hearing featured such opinions as those of Senator John Thune (R-SD), who wished to use the proceedings to draft legislation that would “require internet platforms to give consumers the option to engage with the platform without having the experience shaped by algorithms.” The Senator is happy to accept that artificial intelligence “powers automations to display content to optimize engagement” but sees a devil in the works, as “AI algorithms can have an unintended and possibly even dangerous downside”. This is tantamount to wanting a Formula One Grand Prix without fast cars and an athletics competition in slow motion.

Facing the senators from Google’s side was Maggie Stanphill, director of Google User Experience. Her testimony was couched in words more akin to the glossiness of a travel brochure with a complimentary sprinkling of cocaine. “Google’s Digital Wellbeing Initiative is a top company goal, focusing on providing our users with insights about their digital habits and tools to support an intentional relationship with technology.” Google merely “creates products that improve the lives of the people who use them.” The company has provided access that has “democratized information and provided services for billions of people around the world.” When asked about whether Google was doing its bit in the persuasion business, Stanphill was unequivocal. “We do not use persuasive technology.”

The session’s theme was clear: oodles and masses of content are good, but must be appropriate. In Information Utopia, where digital Adam and Eve still run naked, wickedness will not be allowed. If people want to seek content that is “negative” (this horrendous arbitrary nature keeps appearing), they should not be allowed do. Gag them, and make sure the popular terms sought are white washed of any offensive or dangerous import. Impose upon the tech titans a responsibility to control the negative.

Senator Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) complained of those companies “letting these algorithms run wild […] leaving humans to clean up the mess. Algorithms are amoral.” Tristan Harris, co-founder and executive director of the Centre for Humane Technology, spoke of the competition between companies to use algorithms which “more accurately predict what will keep users there the longest.” If you want to maximise the time spent searching terms or, in the case of YouTube, watching a video, focus “the entire ant colony of humanity towards crazytown.” For Harris, “technology hacks human weaknesses.” The moral? Do not give people what they want.

The rage against the algorithm, and the belief that no behavioural pushing is taking place in search technology, is misplaced on a few fronts. On a certain level, all accept how such modes of retrieving information work. Disagreement arises as to their consequences, a concession, effectively, to the Google user as imbecile. Stanphill is being disingenuous for assuming that persuasive technology is not a function of Google’s work (it patently is, given the company’s intention of improving the “intentional relationship with technology”). In her testimony, she spoke of building “products with privacy, transparency and control for the users, and we build a lifelong relationship with the user, which is primary.” The Senators, in turn, are concerned that the users, diapered by encouragements in their search interests, are incapable of making their own fragile minds up.

The nature of managed information in the digital experience is not, as Google, YouTube and like companies show, a case of broadening knowledge but reaffirming existing assumptions. The echo chamber bristles with confirmations not challenges, with the comforts of prejudice rather than the discomforts of heavy-artillery learning. But the elected citizens on the Hill, and the cyber utopians, continue to struggle and flounder in the digital jungle they had seen as an information utopia equal to all. For the Big Tech giants, it’s all rather simple: the attention grabbing spectacle, bums on seats, and downloads galore.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2FKpeOu Tyler Durden