While the market has been far more focused to comparisons between the current period and what happened during the bursting of the credit bubble in 2006/2007 and the subsequent global financial crisis of 2008 primarily in the monetary arena, where the Fed launched a rapid sequence of rate cuts which ultimately culminated with the GSE nationalization, the Lehman failure, the AIG fiasco and the start of QE, another, perhaps more interesting observation was made recently by Deutsche Bank’s FX strategist Robin Winkler who writes that “the cyclical stress on global financial imbalances has reached levels last seen on the eve of the financial crisis.”

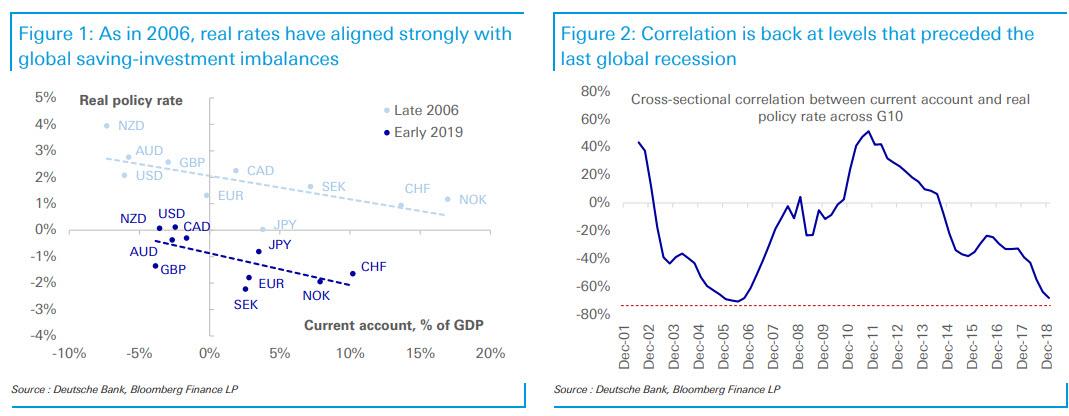

As Winkler details, one red signal is that the correlation between real policy rates and current account imbalances is as high as at pre-crisis peaks, as shown in the charts below.

Specifically, the real rate spreads required for the deficit countries to attract capital flows from the surplus countries are as extreme as in 2006, before adjustment kicked in.

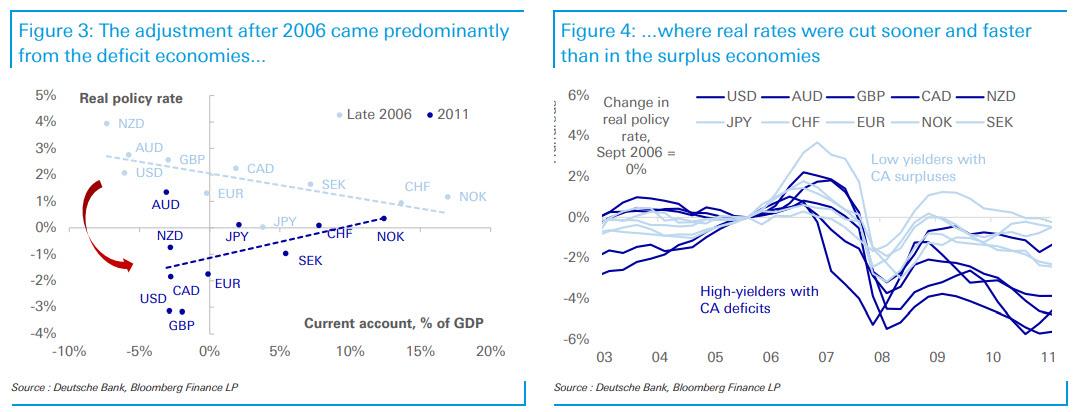

So what happened after 2006? As cross-border capital flows froze, global imbalances were no longer sustainable and needed to shrink. This adjustment, according to Deutsche Bank, came predominantly through a sharp decline in real rate in the Anglo-Saxon deficit countries, rather than in the European and Japanese surplus economies.

Several years later, at the end of the adjustment process, around 2011, the debtors had cut their deficits by about half on average but at the expense of real rates falling below rates in the creditor economies. Accordingly, the Anglo-Saxon currencies underperformed on average.

What about structural changes over the last decade?

According to Winker, today’s global economic system differs in two major respects from the years before the crisis.

- On the one hand, real rates are already materially lower than in 2006, limiting central banks’ policy space.

- On the other hand, global imbalances are less pronounced than in 2006, possibly limiting the magnitude of adjustment.

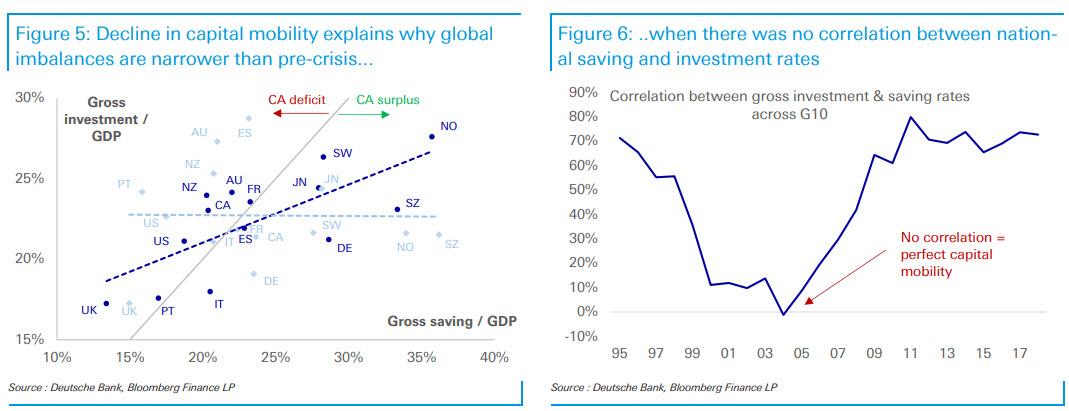

This suggests that like the secular decline in real rates, the decline in global imbalances is structural: the perfect capital mobility that advanced economies achieved before the crisis – marked by a complete decoupling of national saving and investment rates – was never restored during the recovery: investment has been more constrained by domestic savings, especially in countries that had binged on foreign debt before the crisis, as shown in the final two charts.

Why does all this matter? Because as the DB FX strategist sumamrizes, “the net effect of these structural changes is that the global financial system might be more robust to a shock such as a full-blown trade war, but that the burden of

adjustment will be even more asymmetric than last time. This is because monetary policy in the surplus economies is already very close the effective lower bound, and arguably because appetite for fiscal stimulus in these countries has diminished further.”

Thus, even if the starting point for the deficit countries is less fragile than in 2006, their central banks and currencies will likely need to do even more of the work, which in a world where even the BIS is warning that central bank ammo has been largely exhausted, is increasingly improbable with every passing day.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2Gea0Sr Tyler Durden