China’s economic slowdown and heavy debt load is affecting everybody in the country – even it’s “jewelry queen”, Zhou Xiaoguang, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Zhou, who went from selling trinkets on city streets to taking a seat in China’s parliament and becoming Ernst & Young‘s “Entrepreneur of the Year” was faced with the reality of being unable to pay her company’s billions of dollars in debt while in a bankruptcy court in April.

She is just one example of a massive debt burden taking its toll on China.

China has relied on borrowing to fuel its expansion for at least a generation. In 2018, the country was known for creating four billionaires a week and is number one globally in self-made fortunes. But this quick pace of growth, with many borrowing heavily in the process, also masked companies’ strategic mistakes.

Fueled by debt, many over-expanded into crowded sectors and now those mal-investments and mis-allocations of resources are coming back to bite them.

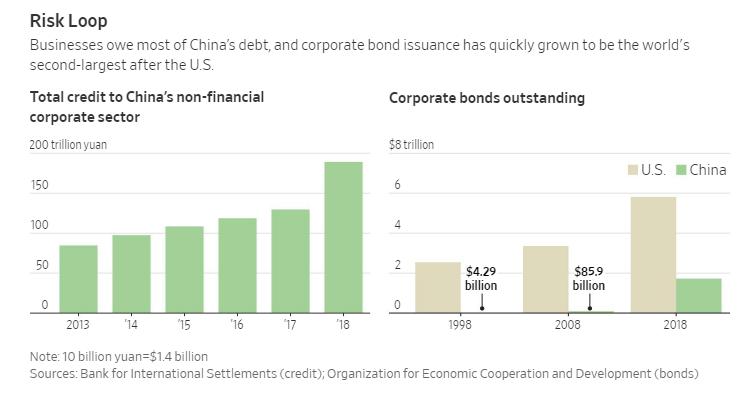

Over the past decade, the overall debt of the country has quadrupled to about three times the value of last year’s national output. Corporate debt makes up 2/3 of the total, amounting to more than $26 trillion last year. Most of the money is owed by government-run companies, but the stress is starting to surface also at private companies, who have less wiggle room with creditors and less support from the government.

For instance, Chenxi Group was decimated by lenders last year when they suddenly decide to call in loans. Earlier that year, the founder of machine maker Zhejiang Jindun Group committed suicide, leaping to his death, leaving the company to later reveal that it owed about $1.4 billion to loan sharks.

This year, Dong Wenbiao’s jet-maintenance to elder-care conglomerate, China Minsheng Investment Group, missed debt payments several times by days or weeks before making good on its obligations. In other words, the cracks in the surface of starting to show.

Joseph P.H. Fan, a professor of finance and accounting at Chinese University of Hong Kong said:

“Many Chinese entrepreneurs tend to borrow as much as possible, even if the core business doesn’t need it.”

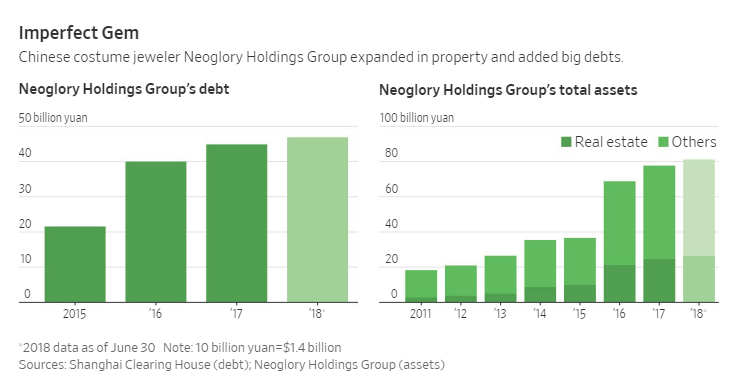

Fan called Zhou’s company, Neoglory, a “textbook example” of the country’s misallocation of financial resources.

Neoglory fueled its evolution into a conglomerate through borrowings that ballooned to $6.8 billion even though cash was tight and profits were weak. The company took on new risks to borrow as it progressed, including tighter covenants and shorter payback schedules. When the company defaulted on a bond payment in mid September, its troubles became very evident.

Zhou commented:

“Though winter may be tough to live through, it’s a good time to do introspection.”

Chinese courts have now ordered Zhou’s assets frozen.

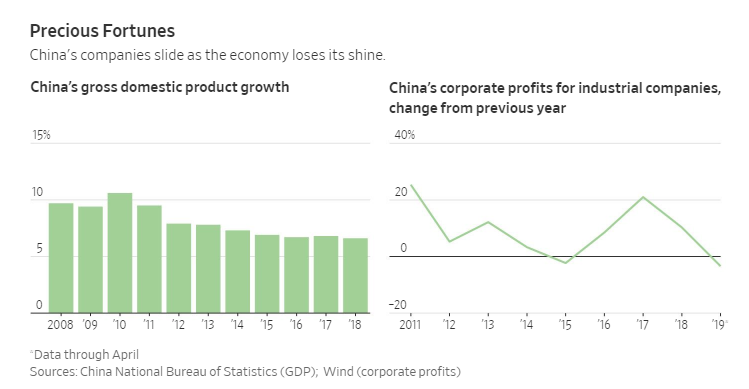

Starting in 2017, Beijing started to dial back an excess of lending by the financial sector – this became a deleveraging that caused shortages at many private companies. This crunch exposed egregious fundamental problems. At the same time, China’s broader economy was losing momentum. Its expansion maxed out at 10.6% in 2010 and now economists are hardly optimistic that the government’s bottom line 6% target will be achieved this year.

The country desperately needs companies that might lead China to a new stage of development that’s less dependent on construction and exports. The debt load is making it difficult for business owners to reinvest in the economy and the trade dispute with the United States continues to wear away at the country’s confidence.

And the cracks continue to show: last month, a government takeover of Baoshang Bank, sparked problems for other small banks and headaches for customers. It was the first bank takeover by regulators in decades and caused near panic.

The corporate bond market is a small part of the puzzle but is relatively transparent compared to lending. Chinese companies last year had $1.72 trillion in debt securities outstanding, which was the second highest after American companies, who carry $5.81 trillion.

Economists say the acceleration of the borrowing is worrisome. This acceleration has often proceeded recessions in other countries, and happened right before the 2008 crisis. Corporate bond demand weakened in 2018 and Beijing has now reversed its stance on lending and is encouraging banks to lend more.

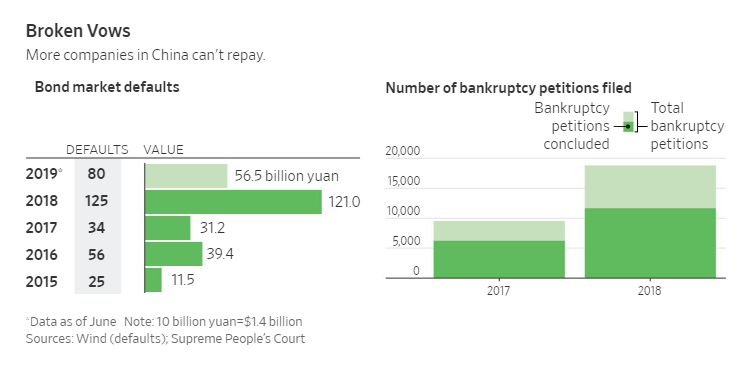

More than 18,000 companies filed bankruptcy petitions in Chinese courts last year, which is about twice as many as the previous year. Bankruptcy had previously been a rare action to take in China. Bond defaults also hit record numbers last year at 125, which was five times the number in 2015. Defaults are running at an even faster pace in 2019 so far.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2G2ZvRA Tyler Durden