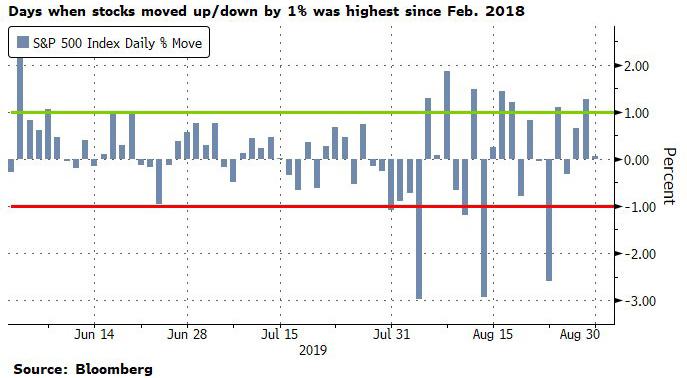

For equity markets, August was the most violent month of 2019, with the S&P tumbling 2.6% or more on at least three occasions, the same as the number of instances when the Dow plunged almost 1000 points – the worst since Q4 of 2018 when the S&P briefly entered a bear market – only to rebound furiously after Mnuchin’s infamous Christmas Eve phone call. Worse, in August the number of days when the S&P moved up or down by more than 1% was the highest since the February 2018 inverse VIX ETN implosion.

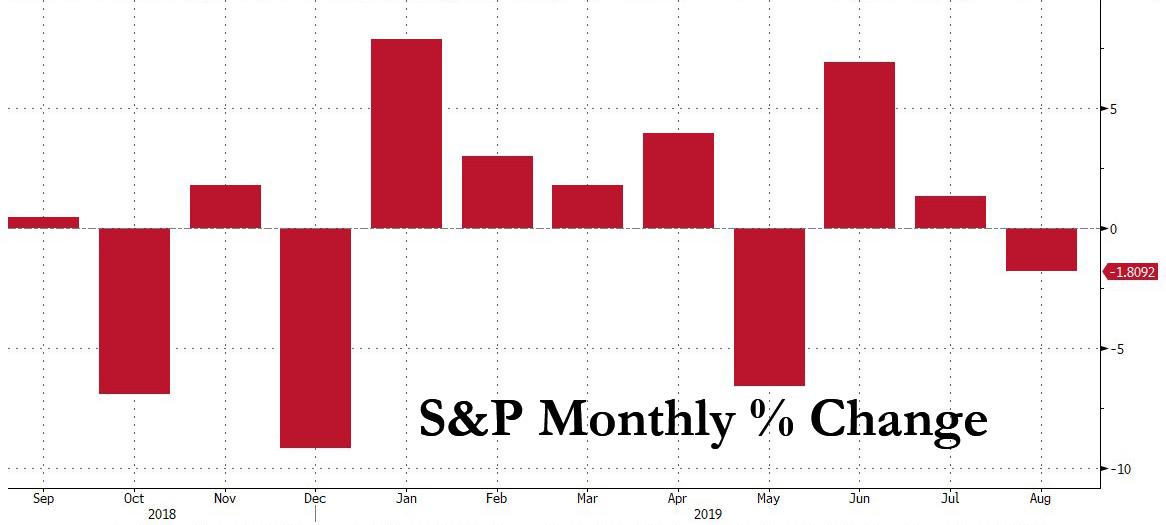

Yet despite all the vomit-inducing day-to-day surges and drops, anyone who took a month-long vacation would hardly believe what had happened: from the first day of the month, to the last, shares had one of their smallest monthly moves of the year: down just 1.8% on the S&P 500, only July had a smaller monthly amplitude.

Additionally, there were twenty-two August trading days, of which 10 down, 12 up. And continuing the symmetry, the vol index that on certain days surged as much as 50% higher than where they started settled back to where they began.

Yet while the daily August gyrations were one rollercoaster too much for most of the human traders still trading this “market” for a living or hobby, September is shaping up even worse, not least of all because September is traditionally the most volatile month. There is also a barrage of newsflow and geopolitical events – not to mention another rate cut by the Fed (which is priced in with 100%+ probability by the market) that ensure non-stop daily drama and even more market volatility than experienced in August.

It all starts with the week ahead, when as BMO’s Ian Lyngen writes, top tier data will once again be on offer for a market that, frankly, doesn’t seem compelled by such passé details. While the trade war has provided the bulk of the trading direction throughout August, in the coming week the emphasis will return to gauging exactly where the real domestic economy stands in terms of growth and inflation. As Lyngen previews, “between ISM, NFP, AHE, and UNR there will be plenty to decipher (or at least unabbreviate).”

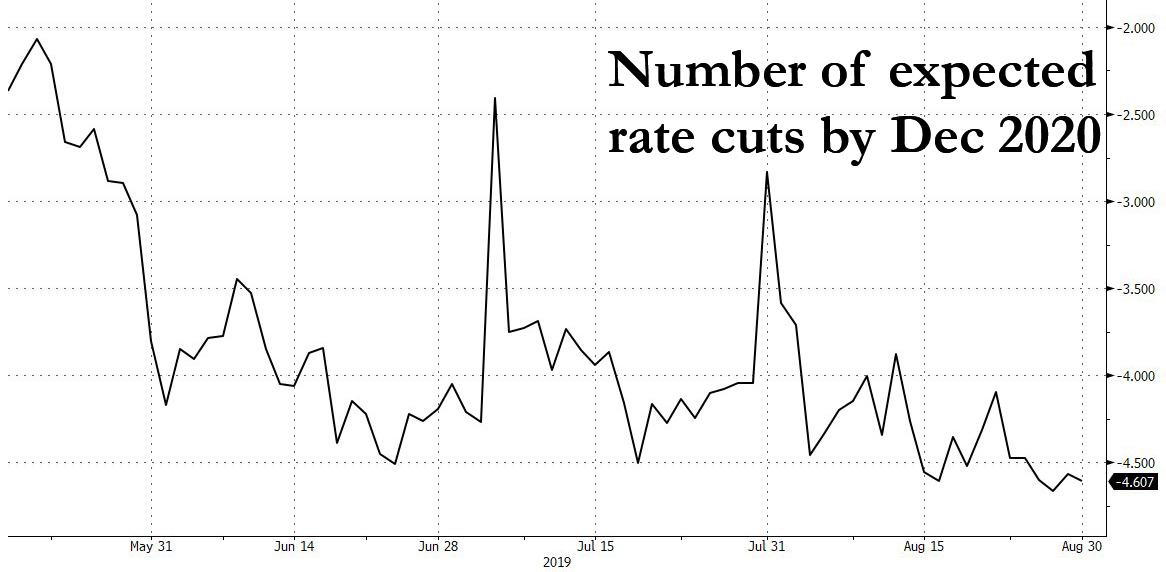

Meanwhile, as the September FOMC meeting approaches, the conversation will again return to what may well be the most important question of all: how many additional quarter-point cuts will comprise this ‘fine tuning’ effort; one, two, or possibly more? Needless to say, yet BMO does so anyway, “the most significant Fed event-risk this autumn will be communications surrounding the most likely path of policy rates.”

Of course, among everything else, investors will be seeking clarity whether 2019 will mirror the 1990s (75 bp of aggregate rate cuts) as per the “mid-cycle adjustment”, or if the fallout from the trade war has done more damage to the global economy and therefore warrants even greater accommodation, and is indeed just the start of an easing cycle (even as trade war is set to send prices of imported goods sharply higher, potentially unleashing stagflation).

According to BMO, it isn’t difficult to envision a scenario in which the Committee updates the economic projections and dot-plot to reflect 75 bp in total and a period of policy stability to assess how much benefit the effort delivers; relying on the classic lagged impact logic. In a world in which the greatest “uncertainty” wasn’t continuing to expand, we’d expect this to be the path of least resistance, Lynger writes. After all, “the US economy appears to be on solid footing and inflation, while still low, is heading in the correct direction”. Alas, as the rates strategist admits, “we’re left in an environment of twitter and state-owned media dictating US rates.”

Which brings us to the punchline, namely that the ever-expanding list of worries keeping BMO up at night “now includes an attempt by the Fed to moderate expectations for easing beyond 1.63% (i.e. two additional quarter-point cuts).” Needless to say, the market – which is pricing in almost 5 rate cuts by Dec 2020, will not be happy by any unexpected Fed hawkishness.

As such, no matter what happens in September, the balance of the year will be an important litmus test for the market’s understanding of the Fed’s reaction function to developments impacting the global growth outlook rather than the domestic realities. In this context, BMO maintains that “the Fed has become the defacto central bank to the world, even if reluctantly.”

However, that doesn’t necessarily imply Powell won’t at least attempt to push back and by crafting a ‘wait and see’ or ‘data dependent’ message into year-end the Fed would be putting the onus elsewhere to combat the risk of a global recession. Furthermore, Powell needs a market trigger to give the market the outcome it desires, namely 6 rate cuts by Dec 2021.

So what happens if Powell follows Dudley’s suggestion, and balks at more rate cuts than what he telegraphed. Fire and brimstone come to mind.

In the event it’s 75 bp (total) and done, the BMO rates analysts claim that the reaction of the longer-end of the curve will be particularly telling as to investors’ perception of the risks of an actual US recession in 2020. A bearish resteepening will be a vote of confidence for Fed credibility and would be predicated on the domestic data continuing to reflect tight labor conditions and inflation that’s trending higher.

This isn’t as off-consensus as it might initially appear, despite the chorus of ‘race to zero’ calls which abound. Should this come to pass, 10-year yields with a 2-handle will be an intuitive target. To a large extent, this risk supports a focus on the interim data even as the market retains a pavlovian response to @realDonaldTrump.

By induction, the worst case scenario would be if the petulant market meets the Committee’s efforts at easing restraint by an even deeper inversion of the yield curve, presumably in a bullish outright move for 10s and 30s. This would be immediately read as another “policy error” reaction, and is the outcome which troubles BMO the most “insofar as it would effectively lock the Fed into even lower policy rates and exacerbate the global race to zero rates.” This, as Lyngen concludes, is a very long way of saying that “Trump can only trump data so long.”

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2Pv6cmx Tyler Durden