Morgan Stanley Asks “What Returns Can Long-Run Investors Expect In This Market”, Offers Frightning Answer

Authored by Andrew Sheets, chief cross-asset strategist at Morgan Stanley

Morgan Stanley’s Research department is currently working on, and debating, what we think the market will look like in 2020. But before thinking about the year ahead, it can be useful to take an even longer perspective. If we put aside the noise around politics and trade, ignore the market’s obsession about every word that central banks utter, or every data release, and step back from it all, what sort of returns can a long-run investor expect from this market?

This is not purely an academic exercise.

Assumptions about the long-run return outlook have real implications for how investors think about retirement security, how institutions think about solvency and how asset allocators think about strategic tilts. Long-run views of the market have limits; by being rooted in valuation, they are driven by a factor that often has little bearing on performance over the next 6 or 12 months. But valuation also has its advantages, proving far more accurate than any other variable in determining what the 5- or 10-year experience of an investor will be.

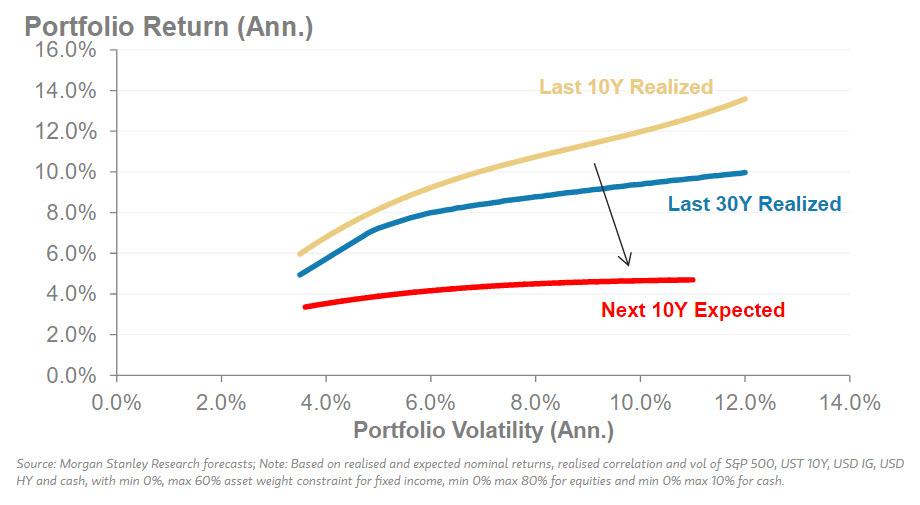

And at the moment, that experience looks challenging: On our estimates, the expected return of a US 60/40 portfolio of stocks and government bonds will return just 4.1% per year over the next decade, close to the lowest expected return over the last 20 years, and one that has only been worse in 4% of observations since 1950.

For a European investor, that blended 60/40 return is also 3.9%, better than just 6% of historical observations since 1970. And lest you think we are placing our hand on the scale, other approaches to estimating long-run returns can lead to even lower long-term numbers, especially if one assumes that currently above-trend margins need to fully mean-revert (we do not).

If we put this in terms of portfolio theory, our long-run return assumptions suggest an unusually low ‘efficient frontier’ for portfolio construction. This frontier is flattest for US dollar assets, and steeper for European and Japanese assets, thanks to higher equity risk premiums.

An important caveat here is that expected returns for the market have looked low before, only to be bailed out, so to speak, as central banks eased policy and pushed prices up ever higher. But it’s important to remember that these higher prices are simply pulling forward ever more future return to the present. That’s great for today’s asset owners, especially those close to retirement. It is much less good for anyone trying to save, invest or manage well into the future, who face an increasingly barren return landscape.

Indeed, we think that there remains an underappreciation of the costs of easy policy and its pull-forward of returns; it is not a free lunch:

- First, by pressuring insurance and pension solvency, low rates, ironically, may drive less ability to take risk through traditional higher-beta assets, such as equities.

- Second, for investors who are able to move out the risk curve, low return in public equity and bond markets drives more money into illiquid corners of the market.

- Third, by confronting individual investors with low returns, it increases the pressure to save more to hit a given level of retirement savings, potentially one reason why the savings rate in developed markets remains stubbornly high.

Do any markets offer a better long-run story? We’d highlight two: UK equities, which trade at a historically large discount to global markets, show little sign of over-earning or margin extension versus history and enjoy a high dividend yield, and emerging market hard currency debt, which offers higher expected long-run returns than other bond assets of similar volatility, on our framework.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 11/03/2019 – 18:50

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2JNp9f1 Tyler Durden