China Braces For December D-Day: The “Unprecedented” Default Of A Massive State-Owned Enterprise

Something is seriously starting to break in China’s financial system.

Three days after we described the self-destructive doom loop that is tearing apart China’s smaller banks, where a second bank run took place in just two weeks – an unprecedented event for a country where until earlier this year not a single bank was allowed to fail publicly and has now had no less than five bank high profile nationalizations/bailouts/runs so far this year – the Chinese bond market is bracing itself for an unprecedented shock: a major, Fortune 500 Chinese commodity trader is poised to become the biggest and highest profile state-owned enterprise to default in the dollar bond market in over two decades.

In what Bloomberg dubbed the latest sign that Beijing is more willing to allow failures in the politically sensitive SOE sector – either that, or China is simply no longer able to control the spillovers from its cracking $40 trillion financial system – commodity trader Tewoo Group – the largest state-owned enterprise in China’s Tianjin province – has offered an “unprecedented” debt restructuring plan that entails deep losses for investors or a swap for new bonds with significantly lower returns.

Tewoo Group is a SOE conglomerate, owned by the local government and operates in a number of industries including infrastructure, logistics, mining, autos and ports, according to its website. It also operates in multiples countries including the U.S., Germany, Japan and Singapore. The company ranked 132 in 2018’s Fortune Global 500 list, higher than many other Chinese conglomerates including service carrier China Telecommunications and financial titan Citic Group. Even more notable are the company’s financials: it had an annual revenue of $66.6 billion, profits of about $122 million, assets worth $38.3 billion, and more than 17,000 employees as of 2017, according to Fortune’s website.

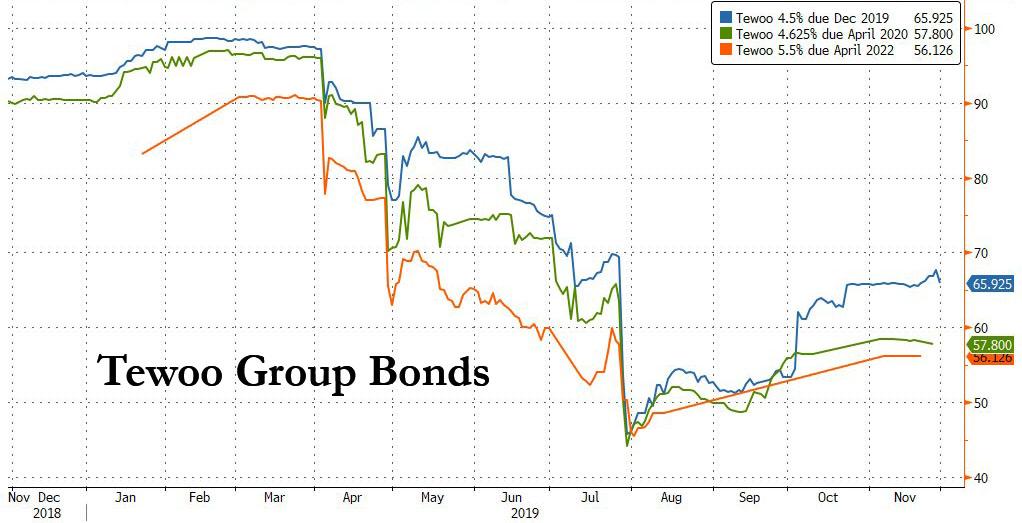

The state-owned company is neither publicly listed nor rated by the top three international ratings companies, although it does have publicly traded bonds whose performance in recent months has been nothing short of terrifying for anyone who thought purchasing a company explicitly backed by Beijing can never fail.

As one can deduce from the above chart, the first time Tewoo Group’s financial difficulties emerged was in April when it sought debt extension from its lenders on its offshore, dollar bonds and sold copper below market rates amid a cash crunch. At that time, Fitch Ratings – the only rating agency to appraise the company’s credit standing – slashed the company’s credit score first from BBB to BBB- on April 18, and then by a whopping six notches, from BBB – to B- on April 29, to reflect its weak liquidity and higher-than-expected leverage.

According to Bloomberg the company has proposed an exchange/tender offer on the three dollar bonds due to mature over the next three years, as well as a perpetual note. What makes what would otherwise be a mundane exchange offer in the US, is that this is the first ever distressed plan of its kind from a state-owned Chinese firm.

What is just as striking is that the Tewoo Group – with its $66 billion in revenues and $38 billion in assets – is likely to default on its $300 million dollar bond due Dec. 16, a Bloomberg source said, unless the exchange is consummated. This means that the company’s bondholders have just a few weeks to decide between either taking as much as 64% in losses or accepting delayed repayment with sharply reduced coupons on $1.25 billion of dollar bonds, something which the rating agencies will describe as an event of default.

A de facto default by Tewoo would be considered a “landmark case,” said Cindy Huang, an analyst at S&P Global Ratings. Central government support for SOEs is likely to be selective in the future, while local government aid will be limited by the slowing economy and weaker fiscal position, she said.

The “distressed exchange offer” comes after Tewoo Group said last week it would be unable to pay interest on a $500 million bond, prompting Industrial & Commercial Bank of China to transfer $7.875 million to bondholders on its behalf. ICBC provided a standby letter of credit on the note – a pledge to repay if the borrower can’t. However, the firm’s remaining $1.6 billion of dollar bonds lack such protection.

Worse, Tewoo Group is already in effective default after some of its units previously missed local debt payments – in July, Tianjin Hopetone missed a coupon payment on its 1.21 billion yuan note sending the company’s dollar bonds tumbling below 50 cents on the dollar, while Tianjin Haoying Industry & Trade missed a loan interest payment due in June. Also in July, rating agency Fitch – which somehow missed all of this when it was rating the company investment grade – withdrew its rating on Tewoo Group due to insufficient information to maintain the ratings. It last rated the issuer at B-.

And as furious bondholders scramble to demand an explanation how a state-owned enterprise can default, Beijing is already bracing for the inevitable next steps: earlier this month, Tianjin State-owned Capital Investment and Management, an entity wholly-owned by the Tianjin municipal government, was appointed to manage the company’s offshore debt. For now, the entity has no plan to hold controlling stakes in Tewoo Group, although that will likely change as soon as the company’s financial situation fails to improve. Meanwhile, Tewoo Group said it plans to take a series of debt management measures, by which we assume it means it will restructure its debt.

The fact that a state owned enterprise such as Tewoo has just days before it defaults, in either a prepack or “freefall” form, suggests that Beijing will no longer bail out troubled SOEs, let alone private firms, perhaps due to the strains imposed by the economy which is slowing the most in three decades. It also raises concerns over Tianjin, where it’s based, following a series of rating downgrades and financing difficulties suffered by some of the city’s state-run firms. The metropolis near Beijing also has the highest ratio of local government financing vehicle bonds to GDP in China.

In short, if there a glitch with Tewoo’s default, the Chinese dominoes could start really falling.

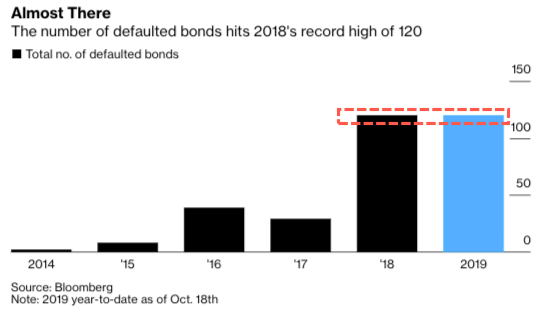

Since the first SOE bond default emerged in China’s domestic market four years ago, 22 such firms have failed to make good on a combined 48.4 billion yuan ($6.9 billion) onshore bonds as of the end of October, according to Guosheng Securities. However, as Bloomberg adds, despite periodic scares such as late repayment, Chinese SOEs have yet to suffer any high-profile default in the dollar bond market since the collapse of Guangdong International Trust and Investment Corp. in 1998.

Tewoo would be precisely that high-profile default.

* * *

There were early signs of Tewoo Group’s debt crisis. The bankruptcy of Bohai Steel Group in 2018 triggered systemic risk in Tianjin’s financial market. The incident involved a large number of local companies and financial institutions, which recorded huge amounts of bad debt. Financial institutions became more conservative in their lending standards, and this resulted in liquidity issues for a number of Tianjin enterprises.

At the same time, Beijing’s deleveraging and capacity reduction reforms made it difficult for a traditionally highly-leveraged company like Tewoo to raise financing. The default in May 2018 by Hsin Chong Group Holdings Limited, a company controlled by Tewoo, showed further signs of financial problems at Tewoo Group.

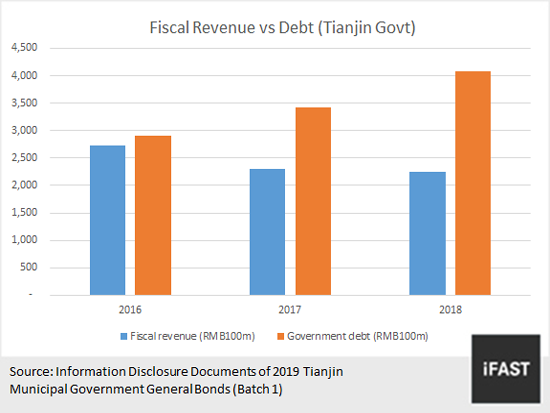

While normally such a critical company as Tewoo would be quietly bailed out by either Beijing or the local province, investors told Bloomberg that the company’s excessive debt levels will limit Tianjin authorities’ ability to lend support to the city’s troubled firms, prompting them to shun the latter’s debt. In July, Tianjin Binhai New Area Construction & Investment Group postponed plans to sell a three-year dollar bond offering amid such concern.

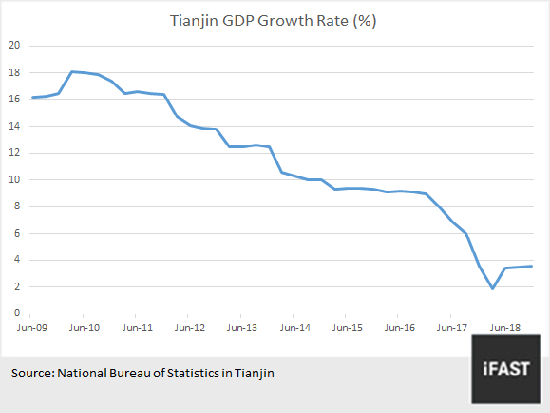

Tewoo’s debt issues that had surfaced from its current crisis may be only the tip of the iceberg. Tianjin’s economic growth has slowed down sharply since the beginning of 2016. GDP growth dropped to 1.9% in the first quarter of 2018. Even as it started to rebound thereafter, the outlook is still pessimistic, with GDP growth in 2018 less than 4%, which ranked last in the country according to iFast.

On the other hand, according to a 2016 report released by ratings agency Moody’s, state-owned enterprises in Tianjin recorded an aggregate liability-to-fiscal revenue ratio of more than 600%, which was the highest in the country.

At the same time, as shown in Tianjin municipal government’s most recent three-year revenue and debt data, Tianjin government’s fiscal revenue has declined significantly since 2017. Fiscal revenue fell by close to RMB40 billion in 2017, while government borrowings rose rapidly. By the end of 2018, debt owed by the Tianjin government was almost double its fiscal revenue.

The bankruptcy of Bohai Steel, a Tianjin SOE, in 2018 may also be a sign that the Tianjin government has lost control over the local debt crisis. Other than Bohai Steel and Tewoo, there have been a number of state-owned companies in Tianjin that are fighting to stave off insolvencies, such as Tianjin Real Estate Group Co. Limited, which owes RMB200 billion in debt. From the above observations, we think that in the event of a default by Tewoo, the company is likely to go into bankruptcy reorganization in a similar way as Bohai Steel, which has brought in capital from the private sector for its corporate restructuring. But for bondholders, recovery of their investments may be difficult, and potential loss heavy.

So with Tianjin unlikely to step up, in the aftermath of Tewoo’s proposed debt restructuring, which will indicate that Beijing will no longer bail out even SOEs, investors’ skepticism about state support for such state-linked firms will collapse, and a default could have wider implications on how investors assess and price their bonds in the future, said Judy Kwok-Cheung, director of fixed-income research at Bank of Singapore.

“Investors would be going back to basics in assessing credit risk in that the company’s stand-alone ability to repay is the first line of defense when it comes to non-repayment risk,” said Kwok-Cheung.

In short, “investors” would be reacquainted with a thing called “fundamentals.” The horror, the horror.

* * *

It gets worse: should Tewoo’s default spread to provincial-backed debt, an already ugly situation could quickly turn catastrophic as Tianjin has the highest debt burden among megacities and provinces in China according to S&P. Earlier this year, Fitch cut ratings on several government-related entities from the city, which is reliant on heavy industry and commodities trading. As a result of having the highest debt, Tianjin also has to slowest growth – Tianjin’s local economy grew by 3.6% last year, the slowest in China; at the end of last year, Tianjin’s government had 407.9 billion yuan worth of debt outstanding, or about 22% of the size of its economy, said the Chinese credit risk assessor.

And just in case the upcoming Tewoo D-Day isn’t troubling enough, Moody’s said that it expected the number of Chinese defaults to continue to rise in 2020 as economic growth sputters and the government attempts to rein in support to indebted companies. Specifically, Moody’s expects 40-50 new defaults in 2020, up from 35 this year, according to Ivan Chung, head of greater China credit research and analysis at Moody’s.

“The regulators’ intention is to reduce moral hazard” while at the same time ensuring any defaults “won’t undermine socioeconomic stability or trigger systemic risks,” Chung said on Wednesday, who added that whereas state support may be available for companies engaged in social welfare projects, for those that are more commercial in nature, “government support may not be so forthcoming,” he said.

Which is the worst possible news for Tweoo’s bondholders.

So what happens next?

Tewoo’s bondholders must quickly decide whether to accept the exchange/tender proposal by December 9 and 10 respectively, with the settlement date due on or around December 17. Since an event of default is now assured, the next big question is what will bondholders of China’s other SOE’s – those who bought bonds on the assumption that China will always bail them out – do next? A flurry of aggressively selling may be just the catalyst that cracks the market if it emerges in the extremely illiquid days just before Christmas.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 11/29/2019 – 16:20

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/37Q4Sjq Tyler Durden