ESG = Excessive Share-price Growth

Via AdventuresInCapitalism.com,

Two months ago, something rather monumental happened, which seems to have been lost to the news-cycle. In a world starved for yield, a company with trailing twelve month free cash flow of $527 million (cash flow from operations – maintenance cap-ex) and net debt of only $593 million could not re-finance debt due in 2022. Sure, the company’s end-markets are currently a little soft and that may have had something to do with it, but even at near-trough cyclical earnings, it has just over a turn of net debt to cash flow.

Why did this happen?

The company in question is Peabody (BTU – USA) and they mine coal. Now, I get it, coal is a dirty word amongst environmentalists, but you don’t get solar panels or wind turbines without structural steel and you don’t get steel without coking coal. US thermal coal may be a dying industry, but more than half of Peabody’s cash flow is now coking coal. Steel is necessary in almost every facet of economic life, yet the financial markets are saying that they will no longer fund a primary building block of economic growth.

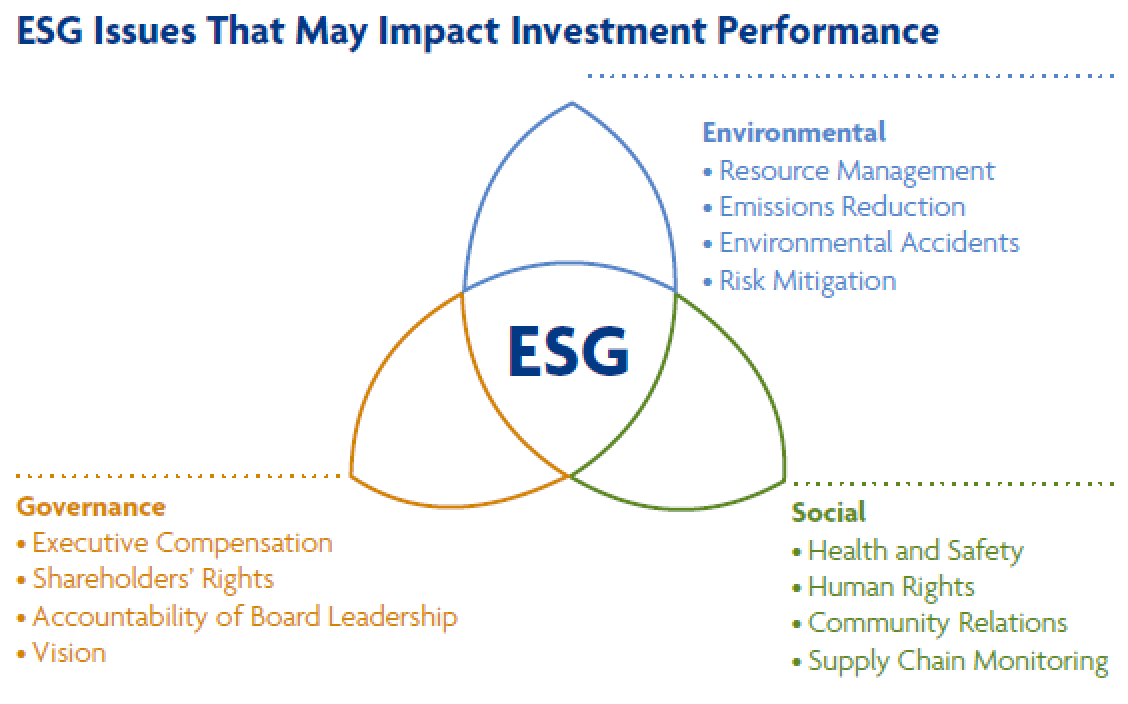

ESG stands for “Environmental, Social and Governance.” I can certainly understand why some individuals or groups may object to investing in various industries. It’s their capital and they can choose to allocate it as they see fit. When they are sizable clients, they can force portfolio managers to divest certain businesses and not make new investments in certain sectors. This all seems logical—the client is always right. However, at this point, ESG has been taken to such an extreme that it is bordering on silly.

Keep in mind that the vast majority of portfolio managers under-perform their benchmarks and only attract fund flows through their marketing departments. Why miss out on fee-earning capital because you haven’t adapted an ESG mandate? Coal? Nope. Oil and gas? Won’t touch it. Tobacco? Bad. Those are obvious, but where will they draw the line? Why not ban soda? That’s just diabetes in a can. Is social media next? What about entertainment—that’s sure to offend someone. What if you don’t agree with a country’s politics? Do you write off whole continents? Clearly, there’s a problem here. You could end up with large portions of the global economy on the no-go list. Once again, I respect an individual’s decision to forgo a particular investment for ideological reasons, but as a consequence, whole sectors of the economy are now cut off from capital.

What should the cost of capital be for a seaborne coking coal miner with a clean balance sheet? It should probably be somewhat in-line with other cyclical industrials. What is Peabody’s current cost of capital? Who knows? They literally couldn’t price their debt. Normally, when a company cannot access traditional debt, it goes to non-standard sources. However, most hedge funds are also funded by endowments and pensions—does a fund want to risk redemptions or turn off future investors over a coal investment? Remember, the whole point of most hedge funds is raising capital and charging higher fees—returns be damned. Somewhere and at some price, there will be funding, but that price is going to be prohibitively high—despite Peabody being unusually safe from a leverage standpoint.

When I look at the coal sector, I mostly see businesses run with minimal net debt. This isn’t because they’re scarred from the last cycle. It’s because they cannot access debt. They worry that their revolvers will not get renewed. They worry that banks won’t even let them maintain bank accounts to process payroll. It’s a crazy world out there when you’re in a pariah industry. Yet, where would the world be without coking coal?

While it’s easy to look at this all holistically and say it’s unfair; as an investor, I see these ESG sectors as primed with opportunity. Who is going to build a new coal mine when the cost of capital is insane? Demand for coking coal grows with economic growth. If new supply is constricted while existing mines deplete, coal pricing should remain robust while returns on capital should continue to stay elevated. Meanwhile, using a normalized coal price, the whole sector trades at somewhere between one and four times free cashflow (I’ll let you choose which normalized price to use) and a lot of that cash is getting returned to shareholders as the companies cannot reinvest easily today. Ask yourself this question; what politician is going to grant a new coal mine the needed permits to break ground? Who is going to allow an expansion for coal handling port equipment necessary for export? Will new rail spurs be allowed? There are bottle-necks building up everywhere in coal that are only going to get worse. These will serve to further raise returns for guys with existing production.

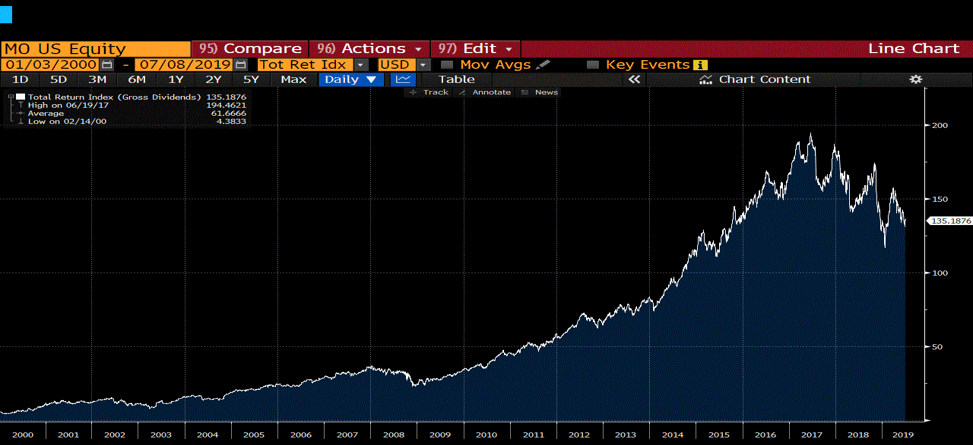

I think back to Phillip Morris (MO – USA) in 2000. It was my largest position at the time. I bought in at something like three times cash flow and a 25% dividend yield. It was one of the best performing large-cap stocks for the rest of the decade despite unit volumes comping negative every single year. Why was it such a strong performer? Because there was minimal new competition, so they were able to raise pricing and earn excess returns, while buying back obscene amounts of stock at single-digit multiples on cash flow. I see a repeat with coal. The more hated it is, the cheaper the shares will be during the buyback, creating massive economic value for remaining equity holders.

Phillip Morris return with dividends reinvested

The same can be said for many other sectors with an ESG overhang. Right now, funds are dumping stock so they can qualify as ESG compliant for 2020. It’s a bloodbath out there. It may get worse and it reminds me a lot of the small-cap liquidations at the end of 2018. Back then, it was obvious that you had to put capital to work into the dislocation caused by redemptions. The difference this time is that I’m not sure when you’re supposed to buy. We may be hitting bottom soon, but I’m not sure yet what the catalyst is to make the shares recover.

However, if companies continue to shrink their shares outstanding by double digit percentages annually, it ought to solve itself before too long—just think back to Phillip Morris. I remember back in 2000, outraged investors were forcing funds to dump cancer-sticks from their portfolios. “Big MO” became a MOnster stock because they shrank the float so rapidly at a time when the shares were so damn cheap. Additionally, no one was starting a new tobacco company. Is anyone building a new coal mine today?

I’m watching closely for a bottom in coal over the next few quarters. I think these ESG sectors that are getting cut off from capital are all going to be next decade’s monsters. One of the few universal constants during the past decade, has been unlimited cheap capital destroying margins and returns on capital for most businesses. The same sorts of “intellectuals” that brought you QE and ZIRP also brought you ESG. As far as I’m concerned, ESG stands for Excessive Share-price Growth. ESG will limit new supply and raise everyone’s cost of capital – which is great if you already have an existing producing asset.

In keeping with my new religion of only buying trends with a Global Micro tailwind, I intend to wait until coal prices also bottom and begin to recover. I don’t care how cheap these things are, I want to know that cash flow is increasing quarter-over-quarter. I assume most of the quant computers have an ESG filter now—but there are probably still a few guys looking to make a buck out there and those computers will cluster in businesses at low-single digit multiples with growing cash flow. Once the turn starts, I don’t think it will stop.

Final point; I care deeply about the environment, but my job is to make money for my clients. Besides, try and build me a solar farm without structural steel. I feel like I’m actually doing my part for progress, because no one else on Wall Street is willing to.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 11/29/2019 – 11:32

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/33xQmJM Tyler Durden