In Stuttering, Stumbling Address Christine Lagarde Vows To Link QE To Climate Change

In her much anticipated first appearance as president of the ECB before at the European Parliament, Christine Lagarde asked EU lawmakers on Monday to give her time to “learn the ropes” of her new job and to reshape the ECB’s monetary policy in what is likely to be a lengthy policy review, and said the ECB will be “resolute” in restoring euro-zone price stability, while stressing that an upcoming strategy review will be wide-ranging, including climate change as well as inflation.

“The ECB’s accommodative policy stance has been a key driver of domestic demand during the recovery, and that stance remains in place,” she said ahead of her first monetary policy meeting at the ECB on Dec. 12.

Similar to the Fed, the former convicted criminal and IMF chief who left Argentina near bankruptcy, has promised an overarching review of ECB business ranging from how it defines its inflation objective to whether it includes a fight against climate change among its responsibilities.

“I’m indeed trying to learn German but I’m also trying to learn central bank language,” Lagarde, a former lawyer told the European Parliament’s Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs in a regular hearing. “So bear with me, show a little bit of patience, don’t over-interpret, if I may say,” said a seemingly nervous Lagarde, who often diverged from the text of her prepared speech and stumbled at times, leaving out phrases or repeating herself.

Lagarde said that a key focus of the review would be to determine whether its objective of keeping inflation at close to but below 2% was still valid, given changes in the global economy.

Speaking a day after it was unveiled that the Fed – which is also in the process of reviewing its policies – was considered launching a new rule that would let inflation run above its 2% target to make up for lost inflation, Lagarde also said the review would look at whether the target should by symmetric, meaning it should be used to tackle both low and high inflation and not just the latter, if the ECB should have leeway in reaching that target, or whether there should be a tolerance band around it.

Of course, just like the Fed, the issue for the ECB is two-fold:

i) ignoring soaring asset price inflation which is where central banks have blown the biggest asset bubble in history, and

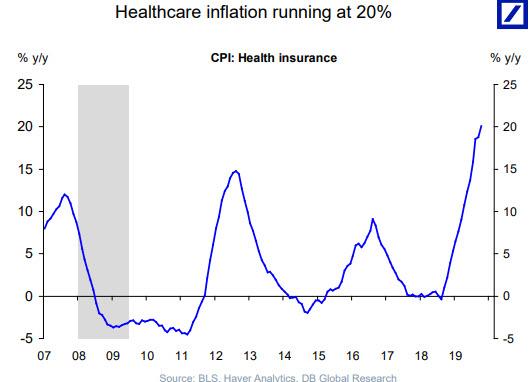

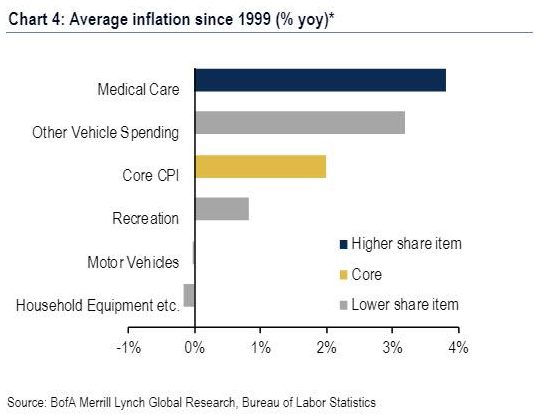

ii) failing to properly measure consumer price inflation, instead applying a spate of adjustments that make it seem inflation is subdued when in reality for many prices are rising so high, the cost of living is no longer bearable.

Then there is the question of whether targeting higher prices is sensible at a time when the middle class is shrinking across the developed world. As a reminder, back in June, a Bloomberg report looked at the stark disconnect between Fed policy and well, everybody else but banks and the 1%.

While the Fed sees low inflation as “one of the major challenges of our time,” Shawn Smith, who trains some of the nation’s most vulnerable, low-income workers stated the obvious: people don’t want higher prices. Smith is the director of workforce development at Goodwill of Central and Coastal Virginia.

In fact, he said that “even slight increases make a huge difference to someone who is living on a limited income. Whether it is a 50 cents here or 10 cents there, they are managing their dollars day to day and trying to figure out how to make it all work.’’ Indeed, as we discussed in “How The Fed’s New Monetary Policy Will Crush America’s Poorest“, it is the low-income workers – not the “1%”ers, who are most impacted by rising prices, as such all attempts by the Fed to “help” just make life even more unaffordable for millions of Americans.

None of this was a concern to Lagarde, however, who said taht the ECB’s “strategy review will be guided by two principles: thorough analysis and an open mind,” Lagarde told lawmakers. “This will require time for reflection and for wide consultation.”

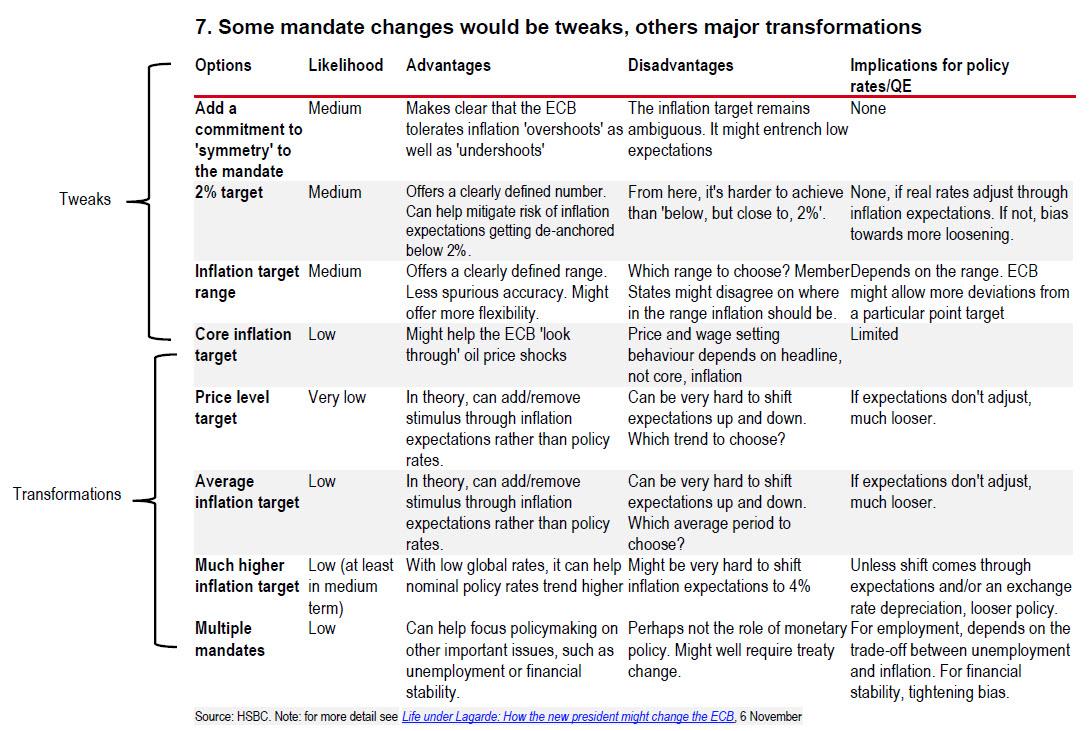

In a recent note, HSBC discussed several options in terms of changing the mandate, from small tweaks to more fundamental changes, which the ECB may pursue. The problem, however, as HSBC noted is that the success of some of these options depends on the degree of confidence in the ECB’s ability to meet it. As a result, the risk of creating a new mandate, only to fail to achieve it as soon as it is implemented, is significant, particularly with policy already so loose and little left in the tank. This was a risk already flagged by Mario Draghi at the September meeting.

These risks, alongside seemingly inevitable compromises in the Governing Council – hawks will likely be averse to any option that risks persistently elevated inflation – lead HSBC to believe that if there will be changes in the ECB mandate as a result of the strategic review, they are likely to be fairly minor. Even moving to a 2% inflation target – removing the uncertainty created by the “below, but close to” – might be too contentious for some.

None of this prevented Lagarde from thinking big. As in climate change big. Because what was more shocking for a central bank which admits it has failed dismally in hitting its price inflation, was its mission creep into seeking to “tame” climate change as well.

Many of the questions at the parliament hearing focused on climate change, an area where the central bank has come under increasing pressure to play a bigger role. In response, Lagarde said that while inflation is the bank’s primary objective, the fight against climate change should be a central part of policy. She said that the ECB’s economic analysis should include the impact of climate change and that its bank supervision arm should also be asking lenders for transparency disclosures and climate risk assessments.

And the punchline: while the ECB’s private sector bond purchases have been market neutral, Lagarde said it was also worth discussing whether climate concerns should impact the ECB’s QE.

How would that work we wonder: “It’s hot outside, so let’s print more money?”

So far the ecofascists have not completely taken over yet, and as we reported previously, German Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann warned against heavy-handed steps such as barring the bonds of polluters from QE, as proposed recently by a group of activists and academics in an open letter to Lagarde. Lagarde said she agreed with Weidmann, but that it doesn’t stop the ECB looking into incorporating climate change into its operations, economic analysis and bank supervision.

To be sure, any mission creep in the ECB’s mandate will only serve to make future monetary easing, well, easier and what better virtue-signaling smokescreen than to use “global warming” as an excuse to print an extra trillion here and there.

Ironically, her linking of QE to climate change took place even as she acknowledged the adverse side effects of the ECB’s ultra-loose policy, and said the review will try to gain a better understanding of how longer-term trends affect what the central bank can control.

One wonders: perhaps the ECB should have conducted such reviews before it bought nearly €3 trillion in assets starting in 2015, long after the European sovereign debt crisis was over, and was merely meant to stabilize risk prices and avoid a market crash.

The take home message however was clear: it is now only a matter of time before the ECB becomes the EcoCB and is “tasked” with a loose, vague and intangible climate change mandate, one which gives the central bank a carte blanche to do virtually anything “in the name of the environment.” Sure enough, at the Parliament hearing, Lagarde said that while the ECB’s primary mandate is price stability, the secondary mandate – to support the general economic policies of the European Union – can cover climate change. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has pledged to turn Europe into the first climate-neutral continent in the world by 2050, and green parties made significant gains in recent parliamentary elections.

Finally, reaffirming the ECB’s most recent assessment of the economy, Lagarde added that growth looks weak but that the ECB was determined to use all it available tools to reach its mandate. Asked to predict what the inflation rate will be in eight year’s time when her term ends, Lagarde refused.

“I don’t think that anybody in their right mind would venture to forecast any number, be it growth or inflation, eight years from today,” she said, yet clearly confident it is her job to predict how the climate will do over the same time period.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 12/02/2019 – 14:05

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2DC3HWK Tyler Durden