“The Lights Are On But No One’s Working”: How China Is Faking A Coronavirus Recovery

Last weekend, we reported that in order to fool the world into believing that its economy is rebounding nicely and that its people have put that entire coronavirus “thing” in the rearview mirror, Chinese officials ordered a factory owner in one of the country’s provinces to “turn on the machines and consume electricity – in his closed factory which has no workers – or he’ll get ‘a visit’.”

Argh. A Wenzhou-based factory owner tells how district officials are telling him his closed factory (he has no workers) must turn on the machines and consume electricity or he’ll get “a visit”. Higher ups are watching the electricity numbers. The anti-Li Keqiang indicator! https://t.co/PTEBARIDW6

— 优述/You Shu (@You_Shu_China) February 28, 2020

Why must the owner of the empty factory pretend the factory is operating? Because “Higher ups are watching the electricity numbers.” And why are higher ups watching the electricity numbers? Because they know that not only the rest of the world is also watching these numbers, but so is China’s population. And absent a rebound in electricity usage, which remain far below prior years even if it is to power unused machines in empty factories, China can’t hold out hope to pretend that February was the kitchen sink month as the level of economic activity simply will not rise for months… unless of course Beijing orders the local population to simply consume for the sake of giving the outside world it is consuming as if things were back to normal.

Only they aren’t, and as we warned last weekend, “instead of Chinese ghost towns, we now have Chinese ghost factories whose only purpose is to try to fool its population and the world that the coronavirus pandemic, which is still raging in China, is under control and the Chinese economy is back on solid footing. Of course, neither is actually happening.”

Fast forward to today, when China’s own Caixin, a Beijing-based media group, picks up where we left off and after conducting its own investigation, has found that local companies and officials are fraudulently boosting electricity consumption and other metrics in order to meet tough new back-to-work targets.

As new coronavirus cases in China slowed in recent weeks, local governments in less-affected regions pushed companies and factories to return to work, typically by assigning concrete targets to district officials. Company insiders and local civil servants told Caixin that, under pressure to fulfill quotas they could not otherwise meet, they deftly did what China always does when in a bind – they cooked the books.

This is how a very desperate China is scrambling to give the world the impression that all is well: leaving lights and air conditioners on all day long in empty offices, turning on manufacturing equipment, faking staff rosters and even coaching factory workers to lie to inspectors are just some of the ways they helped manufacture flashy statistics on the resumption of business for local governments to report up the chain.

In short, the Chinese are simply doing what they always do when reporting “data” – they are making shit up.

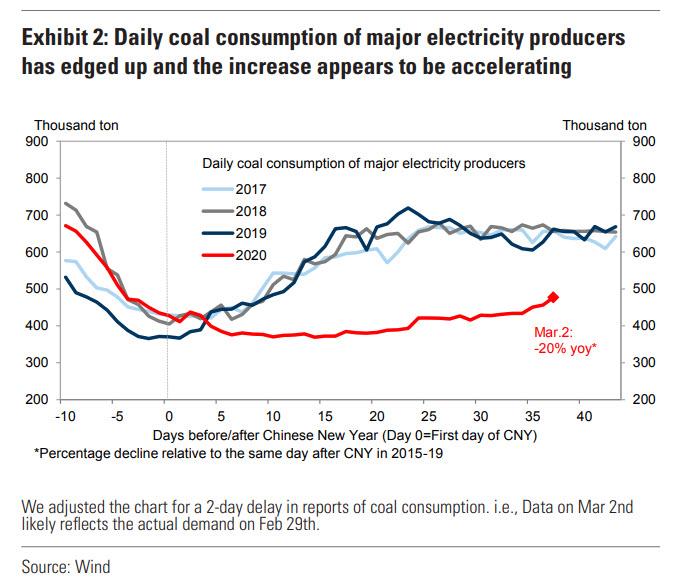

As we pointed out several days ago, electricity consumption data has regularly been used as a proxy for the business resumption rate when reporting to Beijing, and to the public.

The East China province of Zhejiang has been lauded as a prime example of the nation’s industrial recovery from the coronavirus outbreak by China’s top economic planner, which reported on Feb. 24 that its work resumption rate was more than 90%. But a civil servant in one district of the provincial capital, Hangzhou, told Caixin that from Saturday plants were instructed to leave their industrial equipment idling for the whole day, while offices were told to keep computers and air-conditioners running, when Beijing began checking the resumption rate by examining power consumption figures.

Caixin chose not to name the district to protect the identity of the civil servant, who could face repercussions for revealing the information publicly. But reached by phone, one company insider in the district said they saw such directives in multiple corporate WeChat groups. Another said they received the order too, but their operations had already resumed two weeks prior, and its production lines were in normal operation by Feb. 29. Another executive said they were not informed of the electricity use target, and said they were running at about one-fifth of normal capacity, with only a small proportion of machines in use.

Hangzhou’s target was for corporate electricity consumption that day to hit 75% of what it was on Jan. 8, and that it should return to at least 90% of that by March 10.

The real resumption rate in one industrial park in Hangzhou over the weekend was 40%, the civil servant estimated, far below the 75% target. It means that the chart below showing coal usage is as a proxy for electricity demand is, as we suspected, the latest “data” that China is gaming to represent an economy which is nearly 100% stronger than in reality.

Of course, Beijing is well aware of what is going on, and the district official pointed out China is further subsidizing electricity costs as a way to incentivize businesses to resume, saying that many companies would rather waste a small amount of money on power than irritate local officials.

Insiders told Caixin that in some cases, rather than giving companies direct targets, local governments assigned quotas to local district officials who were then directly responsible for meeting them. Those officials would regularly visit the companies, prodding them to resume production in the guise of expressing “care and support.” That pressure is likely what drove them to switch on their machines.

Zhejiang Provincial Government Deputy Secretary-General Chen Guangsheng boasted to press on Feb. 24 that a segment of manufacturing plants in Zhejiang reported a work resumption rate of 98.6%, and service enterprises 95.6%. More than 99% of the coastal province’s companies with annual export value above $10 million had resumed business, the provincial leader said.

Picking up on our post from the weekend, Caixin next writes that a company in Wenzhou, confirmed it had received a designated power consumption target equal to half of the level before the outbreak, and had been running its air conditioners all day long to meet the goal.

Zhejiang is not the only place where the reality on the ground is said to deviate from government figures. In the small industrial city of Botou, some 230 kilometers (143 miles) south of Beijing, Caixin found factories reported by the local government to have reopened their doors had not in fact resumed production.

The head of one told Caixin that despite reports up the chain, the local government’s unwillingness to risk an outbreak meant it had not actually restarted. “The local government still forbids factories to actually resume work,” the executive said. “We have returned to the offices, but production has not resumed at all.”

He further said the Botou government asked him to falsely report the number of employees who had returned to work, and even went so far as to directly coach workers about how to lie if they received calls from inspectors. Prolonged suspension of production had led to the loss of technicians and business orders, he added, because some of the company’s peers in other parts of China had resumed manufacturing ahead of them.

Replying to Caixin’s request for comment on Monday, the Botou government said at least 228 enterprises in the Botou area had resumed business, but some companies might have said they did not because while they were registered as having resumed, they may not have been prepared to immediately commence production. They said companies were permitted to resume normal business after reporting to the local government, but could only begin operation after officials confirmed virus control measures were in place.

A source in a smaller enterprise in Botou told Caixin companies have been allowed to resume production after meeting certain virus containment requirements, but face the further logistical issues as many rural roads remain blocked. Without a way to get raw materials in and send products out, there’s not much point in businesses returning to production.

Open data from Baidu Maps shows overall traffic flow inside the Botou city over the weekend was still less than half of the average last year, after two weeks of slow recovery starting from Feb. 18. Of course, with everyone instructed to pretend as if things are normal on weekdays, the traffic then was in line with prior years.

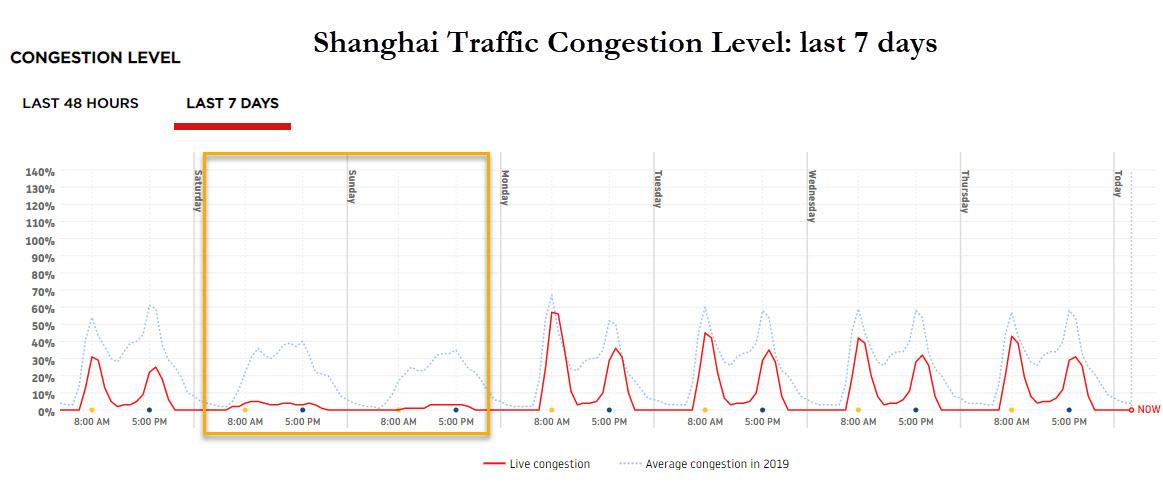

Indeed, this confirms what we have observed previously: that whereas congestion data from weekday is almost back to normal across China’s industrial centers as a result of orders to pretend “all is well”, it is the the weekend traffic that indicates what local residents really think about whether the coronavirus is contained. So what does weekend traffic congestion show? Courtesy of TomTom, here is the last 7 day traffic congestion for Shanghai – while weekdays are virtually back to normal, the catastrophic weekend traffic makes clear that virtually nobody is outdoors on days when the locals aren’t ordered to pretend things have stabilizied, confirming that nobody believes the pandemic has been eradicated.

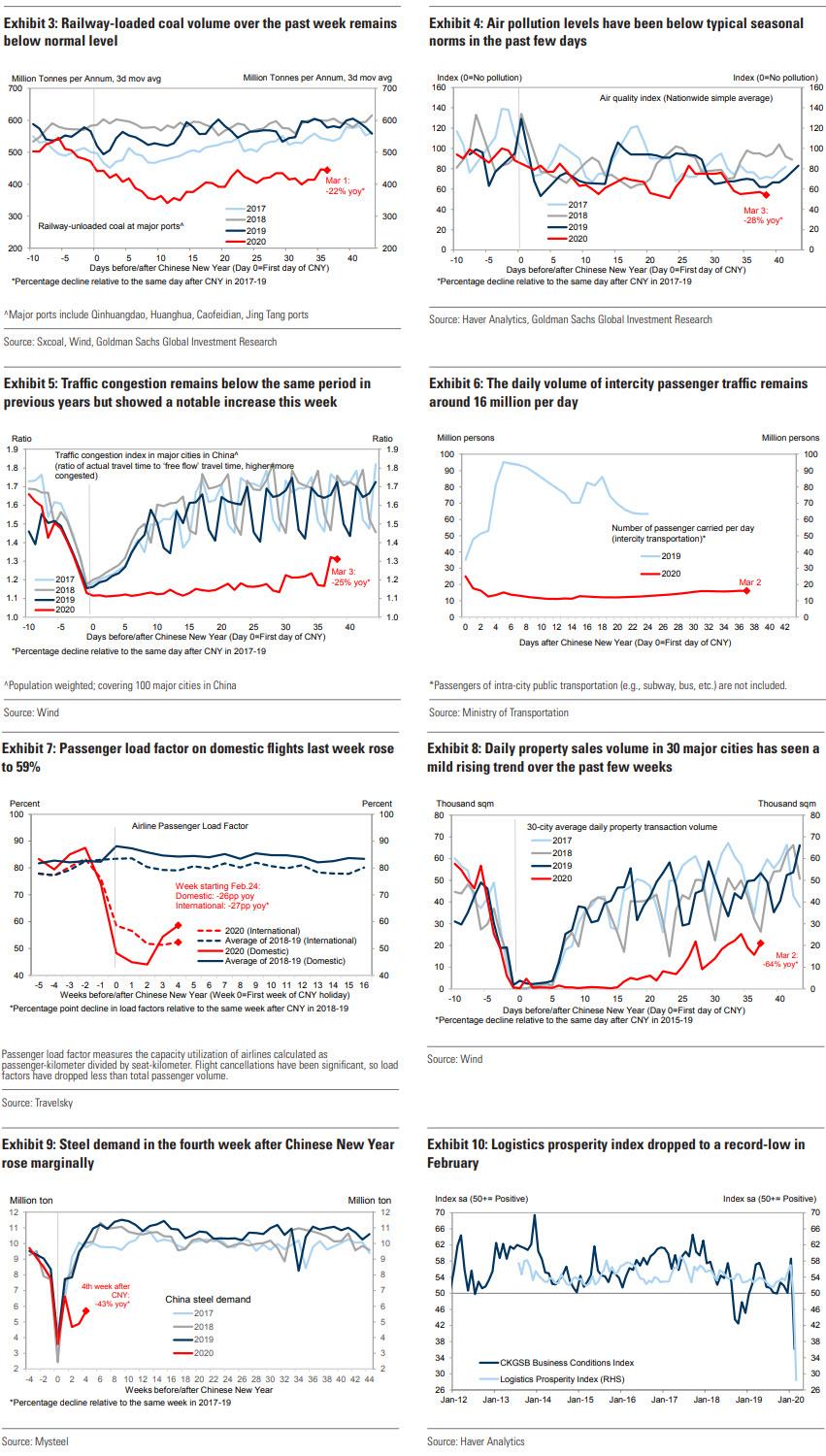

Unfortunately, this also means that none of China’s high-frequency indicators that Wall Street analysts had become so reliant on to determine if the Chinese economy is recovering, and which in recent days have shown a tentative improvement …

… are credible.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 03/05/2020 – 14:10

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2PRCZQz Tyler Durden