LatAm Bailout Veteran Says Emerging Market Crisis Is The “Worst He’s Ever Seen”

With the Nasdaq set to erase all of its 2020 losses after strong earnings from the tech giants, and stocks generally surging on the assumption that, as UBS put it, “lockdowns are lifted by the end of June and do not need to be re-imposed”, especially with today’s favorable if conflicting remdesivir news, it is easy to forget that emerging markets are facing their private hell as a result of widespread economic shutdowns, poor healthcare conditions which will only exacerbate the coronavirus pandemic, the dollar’s relentless strength, and trillions in dollar-denominated debt maturing in the next few years which the chronically strong US dollar will make prohibitively impossible to repay.

But don’t take our word for it: according to Bill Rhodes, CEO of Rhodes Global Advisors and a veteran of countless international bailouts in the 1980s and 1990s, the debt crisis that’s erupted across the world’s emerging markets is “the worst he’s ever seen.”

Rhodes, 84, is perhaps the world’s foremost expert on emerging markets in peril: the former Citigroup executive is a veteran of the 1980s Brady Plan that re-set the clock for Latin America’s struggling economies by creating a new debt structure for developing nations that’s largely in place to this day.

“It’s going to be difficult,” Rhodes said in an interview with Bloomberg discussing the coming EM crisis. “You need to have some sort of coordination between the private and the public sectors.”

The problem: three decades after a coordinated rescue of emerging markets orchestrated by US Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady (the person responsible for the term Brady Bonds) the global pandemic is again challenging the world for a solution, and this time a raft of private bondholders must also be on board. More than 90 nations have already asked the IMF for help amid the pandemic.

The first challenge is that the $160 billion debt renegotiated during the Brady Plan pales next to the $730 billion that the Institute of International Finance says must be restructured by the end of 2020; the final number could be far greater.

Adding to the difficulties of the next global bailout, unlike 1989, when the loans were mostly held by banks and defaults had already happened, now it’s split between hundreds of creditors ranging from New York hedge funds to Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds and Asian pension funds. Getting them all in the same room will be a challenge, forget about getting them all to agree on one outcome.

Following in the footsteps of forbearance protocols enabled across the US, academics and officials are pushing for steps that would allow developing nations to pause bond payments through at least 2020, if not even longer, until the coronavirus fades and economies stabilize enough to analyze debt sustainability. And since one’s debt is always someone else’s asset, that proposal is upsetting creditors on Wall Street who depend on those funds to keep their portfolios afloat and to generate current income.

Meanwhile, G-20 leaders and multilateral organizations are already working toward relief for nations to stay current on debt. The IMF and Paris Club asked the Washington-based IIF to coordinate a standstill, and the United Nations is calling for a new global debt body.

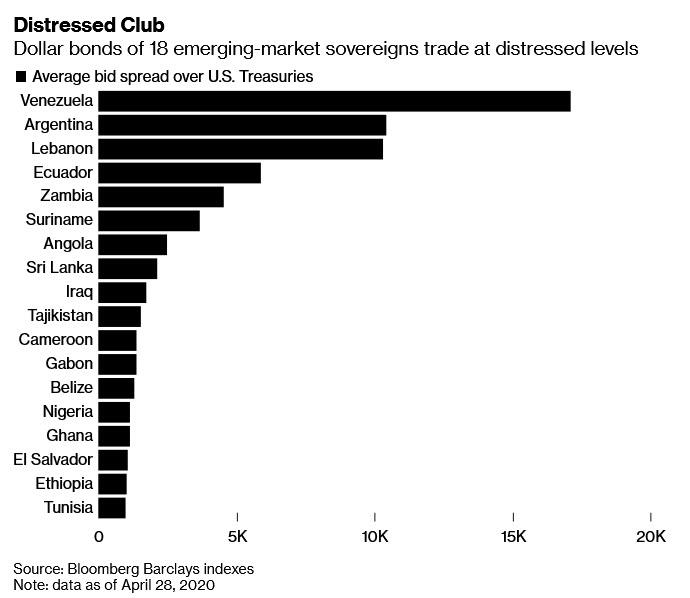

The other big challenge is that bureaucrats have to not only reach a solution, they have a strict time limit in which to do so: dollar-denominated debt from 18 developing nations already trades at spreads of at least 1,000 basis points over U.S. Treasuries. While the top three insolvent outliers – Venezuela, Argentina and Lebanon – were grappling with their own problems before the pandemic, others are fast approaching those levels amid currency sell-offs and record-shattering outflows.

Rhodes’ dire warning echoes that of another EM expert: Anna Stupnytska, Fidelity International’s head of global macro and investment strategy, told Bloomberg “I’m really worried about emerging markets,” adding that Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, South Africa, India and Indonesia may be among the most vulnerable to a virus-related crisis. She expects the coming months to be critical.

Stupnytska, who isn’t expecting a V-shaped economic recovery anywhere, said that weak public health systems, political worries and doubts on central bank independence are “really unhelpful” for EM nations, and that other than parts of Asia, large sections of developing nations are yet to see a peak in coronavirus cases.

“So we are potentially looking at some emerging markets crisis even over the next few months.”

With the clocking ticking, some sort of forbearance on debt payments – currently the most popular idea to help emerging markets – has to be agreed upon and soon; it would also need to extend beyond 2020, according to Anna Gelpern, a law professor at Georgetown University who spent six years at the Treasury. A coordination group could offer standardized terms to all of a country’s creditors that automatically push out payments, however how all creditors will get on the same page is unclear. After all, with memories still fresh of the massive profits Elliott Management earned by holding out on the Argentina debt restructuring early this century, what is to prevent all creditors to pursue this path?

Bloomberg agrees, noting that “it will be no easy task to convince private creditors, especially those with large emerging-market exposure, to take a hit by deferring debt payments.”

Zambia has started talks to postpone its arrears, while Argentina has proposed a plan to restructure its debt that includes a three-year payment moratorium. Neither country has found much traction with its creditors who demand a payment and in full upon maturity.

“Countries that look to markets and are willing to engage market participants have found success in bridging the Covid financial shock,” said an optimistic Hans Humes, CEO of Greylock Capital Management, which has been involved in most emerging-market restructurings over the past quarter-century. Many would disagree with his cheerful assumption.

Then again maybe creditors will find it in their bank accounts, if not hearts, to grant a reprieve: bondholders already granted Ecuador a delay on coupon payments until August, which may save the government as much as $1.35 billion this year, as it deals with one of the region’s worst virus outbreaks and a sell-off in oil.

Alternatively, “the time and resource costs of pursuing market debt relief may outweigh the benefits,” especially if a country plans to default anyway, Goldman’s Dylan Smith wrote in an April 17 note. Plus, “it is not clear that the fiduciary duties of large bondholders toward their investors would allow them to provide lenience to debtors, even if they privately support the initiative.”

And you thought OPEC deals were complicated.

Lee Buchheit, a four-decade veteran of the restructuring world, said forcing each nation to renegotiate on its own would only exacerbate the pain. “Here we have a planet-wide phenomenon that is going to make a number of countries have to face unsustainable debt positions.”

Tyler Durden

Thu, 04/30/2020 – 22:00

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2KMnSVx Tyler Durden