Millennials Are Officially Getting Too Old To Build Wealth

Time is officially no longer on the side of millennials.

In “almost every way measurable”, millennials are up against the clock to build wealth – and are losing ground, according to a new Bloomberg report.

The report speculates that if a Covid “recovery” is even legitimately going to happen (which we take with a large grain of salt), that it may be the last chance for those around the age of 40 to build the wealth they will need for their later years.

But most millennials, instead of basking in an incredible recovery and acutely focusing on re-bulding (or building for their first time) their finances, feel like 40 year old Kellie Beach, a real-estate attorney. She rode out the pandemic like most Americans: “I stayed afloat with credit cards. I was just used to swiping and overspending.”

Now that the government dole is running out and the Covid scapegoat is working its way (albeit, slowly) out of the discourse, it has become clear that it’s time to pay closer attention to her finances. She told Bloomberg: “Now I have this feeling — like this fire — of urgency. I’m not going to be in this place again. I can’t wait to get out of this debt. I can’t wait to save up for my emergency fund and invest again.”

40 year old Dustin Roberts was similarly situated – he had $38,000 remaining in student debt when finally put together what he could to buy his first house in April.

He said: “My dad had always tried to tell me how important it was to buy a house, how that was a mode of financial security for him. I’m making more than my dad did, but am I better off? I don’t know that I can say yes.”

Millennials were 27 years old when Lehman went bankrupt and are now about 40 years old coming out of the Covid crisis. They have ridden out two major recessions during peak saving and investing years, the report notes. William Gale, senior fellow in the Economic Studies Program at the Brookings Institution said: “The Great Recession knocked everyone for a loop. It caused unemployment. It caused slow wage growth. It made it harder to accumulate wealth.”

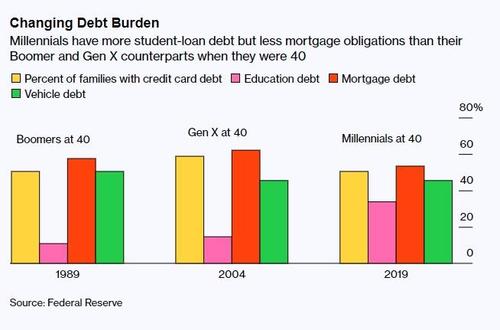

Like Roberts, more millennials borrow to finance college that previous generations. “Millennials, who started college in 1999, paid an average of $15,604 per year for undergraduate tuition, fees and room and board,” Bloomberg wrote. “When Gen Xers and Baby Boomers started college, that number — adjusted for inflation — was about $10,300 for each of them.”

40 year old Summer Galvez went to Clark Atlanta University in Georgia for a couple of semesters before pulling out because it cost too much. She now “relies on her own skills and hustle,” working two jobs and still paying off loans from 20 years ago.

“There are always economic factors that could happen that could just really upend your life,” she said.

Lowell Rickets, data scientist for the Institute for Economic Equity at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis commented: “That’s one of the stark evolutions of the job market, where education has become a greater predictor of success.”

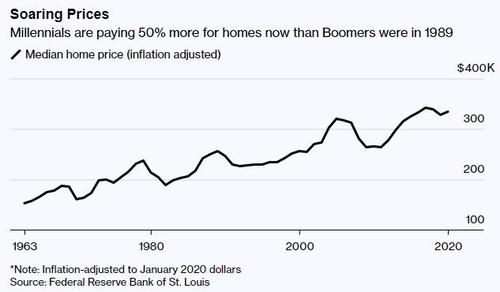

Buying homes has been a scramble coming out of the pandemic, forcing prices higher and contributing to why millennials have a lower home ownership rate than previous generations at the same point in their lives: 61% for millennials versus 68% for Gen Xers and 66% for baby boomers.

Millennials pay a median of $328,000 for homes while boomers only had to pay $216,000, the report notes.

Richard Fry, a senior researcher at Pew Research Center, noted: “The basic way that middle American households build wealth is through their homes. Millennials have been less likely to be homeowners. Fewer of them have begun the process of building home equity.”

William Gale of the Brookings Institute, noted about home ownership: “Conceptually, that could help their wealth accumulation because they’d be paying less for rent and they could save more. But in practical terms of what happens is it’s an indicator of lack of economic status.”

The rise in prices is “great if you’re a homeowner,” Gale said. “But it’s terrible if you’re a renter trying to buy a home.”

Net worths have also declined. Where boomers would have about $113,000 in today’s money in wealth in 1989, that number for millennials has shrunk to $91,000 in 2019. The pandemic – and the ensuing response from central banks – has only served to widen the inequality gap.

“As we diversify the country, if we continue to see these inequities, it suggests that we’re really going to have a hard time achieving financial stability and upward mobility more broadly among American families,” Ricketts said. He also commented about millennials receiving inheritances later in life: “It might be too late for them to take advantage of it and meet some of those mid-life goals that wealth really helps with achieving.”

The simple fact is that millennials are playing a massive game of catch-up; and they’re losing ground. Juan G. Hernandez Ariano, a certified financial planner and director at WealthCreate, stressed the importance of a budget and catching up: “Bottom line: Are millennials behind? Yes. Can you catch up? Yes. How? First and foremost, defining your goals. Once you define your goals: build a budget, improve that budget, diversity not only from an investment perspective but an income perspective.”

Signe-Mary McKernan, an economist and co-director of the Opportunity and Ownership initiative at the Urban Institute in Washington concluded that it isn’t too late just yet: “I don’t think it’s too late. If we set up this stronger foundation for economic security, if it’s institutionalized for everyone, then it could make life better for young millennials, for older millennials, for future generations and for the country as a whole.”

But if you’re a millennial, the clock is ticking…

Tyler Durden

Fri, 06/04/2021 – 13:35

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3wWfQ2z Tyler Durden