Nigerian Influencer “Hushpuppi” Funded Life Of Luxury With Complex Email Schemes, FBI Alleges

For Instagram “influencer” Hushpuppi, also referred to as the “Billionaire Gucci Master” Ramon Olorunwa Abbas, living a life of private jet setting and luxury on Instagram in front of his 2 million followers turned out to not only be his claim to fame, but also the straw that broke the camel’s back for his empire. While many looked on at his life of luxury in awe, questions started to arise about how he obtained, and maintained his wealth. The answer lied in the evolution of the often mocked “Nigerian email scam” that we have all become used to.

Hushpuppi always maintained the questions about his wealth were “the jealousy of so many haters”, a lengthy new Bloomberg profile notes. “As I turn a year older into my 30s today, I want to celebrate all of you out there,” the influencer said to his fans on his 37th birthday. “Those of you who mostly I have never met, spoken to or anything but have been a strong supporter of me through every situation until this point and still riding for me, I want you to know wherever you are that I celebrate and appreciate you today, today is OUR DAY!”

It was one of many posts he made flaunting his wealth and engaging with his followers who supported him while he jet-setted, beefed with celebrities online, and did his best to side-step questions about where, exactly, his success came from.

His captions to his photos would make his life of luxury look like the honest success of the son of a taxi driver and bread salesman from Nigeria. But of those who he likely didn’t celebrate or appreciate was the FBI, who is the driving force behind United States of America v. Ramon Olorunwa Abbas, which alleged in a California federal court that Abbas engaged in “conspiracy to launder money obtained from business email compromise frauds and other scams”.

For example, a small sliver of the cash he received as part of these schemes was $922,857.76 sent by a New York law firm that was supposed to be sending it to one of its clients. A paralegal at the firm received a fax from “someone in Abbas’ orbit” directing her to send the payment to a Chase bank account and initiated the transfer without even thinking twice. The firm didn’t even notice the cash had been misallocated until later in the month.

The transfer was part of a relatively sophisticated “business email compromise” scheme that Abbas and his co-conspirators implemented around the world, the FBI alleged.

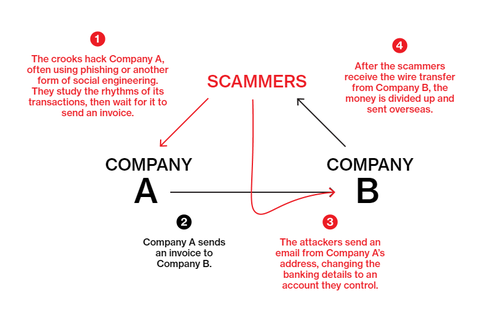

Bloomberg, in their profile, described how the BEC scam works:

BEC attacks started appearing roughly a half-dozen years ago, escalating each year until they surpassed all other forms of internet fraud. The FBI reports there were almost 20,000 such scams against American businesses in 2020 alone, accounting for $1.8 billion in losses, though the variety of BEC crimes can make totals hard to pin down. Crane Hassold, the senior director of threat research at the cyberdefense company Agari Data Inc. and a former FBI analyst, likes to define a BEC as “a response-based impersonation attack that’s requesting something of value”—basically, posing as a legitimate business to trick people into giving away their money.

No matter the flavor, a BEC scam generally begins with someone hacking into a corporate email account often using social engineering tactics like phishing. Once inside, the perpetrators don’t steal anything, not at first. Instead they quietly begin forwarding copies of incoming and outgoing email to themselves. Then they wait. “They watch it for a number of weeks or months, looking for details of certain payments that are going out, understanding who their customers are, looking at communication patterns,” Hassold says. When they spot an invoice coming in or out, they “use that intelligence to insert themselves into an actual payment that is supposed to be due.”

Those who participate in the scheme are loosely networked and work together. There’s different roles for the scheme too: your hackers, your money mules, and even people tasked with controlling international bank accounts that can accept millions of dollars in transfers.

Crane Hassold, the senior director of threat research at the cyberdefense company Agari Data Inc. and a former FBI analyst, told Bloomberg: “These attacks are so realistic-looking, most people don’t give it a second thought. Because when you’re involved in payments like these, you see a lot of these emails every single day. And when it doesn’t raise any red flags, you are not going to go up the chain and do any confirmation. One would expect that when you get into larger and larger and larger amounts of money that are exchanging hands, that there would be some process that requires secondary authorization or something like that. But in many cases, that’s not what actually happens.”

He continued: “I think that most people think of BEC attacks as just basic, boring attacks, and most people don’t think it’s as big a problem as it actually is. When you look at the amount of money that is actually lost to ransomware, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to what’s lost in BEC attacks.”

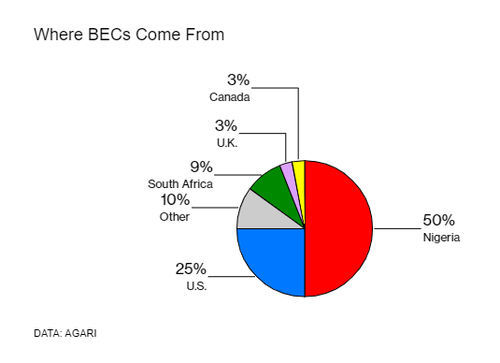

“A lot of the same concepts that go into these BEC attacks, criminals and scammers in West Africa have been doing for decades at this point. Those were all individually targeted social engineering attacks. And essentially what happened was, around 2015, cybercriminals started seeing that they could make more money targeting businesses than they could targeting individuals,” he continued.

People from the neighborhood where Abbas grew up in Nigeria “began to drift into online scamming in the early 2000s”, the report notes. But since no one would associate with them once they revealed themselves as Nigerian, the schemes evolved. “Scams evolved over a decade from money-order fraud to check-cashing scams to romance scams to BECs,” the report notes.

In terms of motivation, aside from the obvious, Abbas appeared to take exception with the system where he grew up, saying in one Snapchat video: “My mother is from the Niger Delta part of Nigeria, where Nigeria’s oil comes from. She has never benefited one dollar. One dollar! And she is over 60 years old.”

Olayinka Akanle, a sociology professor at the University of Ibadan who’s studied youth and cybercrime said: “Cybercrime is a metaphor for a more deep-seated and deep-rooted problem in Nigeria. When people face survival challenges, they innovate. And when they innovate, if there is no system to address their innovation in a very decisive way, it becomes the norm.”

He started to show off the money he was making on Instagram as far back as 2012. Several years later, one of his close associates, Samson Oyekunle, after moving to Houston in 2017, was arrested and charged with “participating in multiple BEC frauds” and was sentenced to 5 years in jail. Abbas had moved to Dubai by then and the walls were closing in him, too. With evidence mounting about how he was making his income, his time ran out in 2020.

When Dubai police raided his hotel room and arrested him in 2020, they were so proud of the takedown, they took a page out of Abbas’ book: they posted the raid on social media.

.@DubaiPoliceHQ takedown “Hushpuppi”, “Woodberry”, ten international cybercriminals in a special operation dubbed “Fox Hunt 2”. pic.twitter.com/E8oOFHZftG

— Dubai Media Office (@DXBMediaOffice) June 25, 2020

You can read the entire Bloomberg feature on Hushpuppi here.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 07/01/2021 – 05:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3dyEjDJ Tyler Durden