Delta Wave Has Likely Peaked In UK, Europe, Goldman Analysts Say

As we have reported, a team of Goldman analysts has been closely monitoring the most recent delta-variant-driven surge in COVID cases in Europe (the trajectory of the outbreak will have an important impact on bank’s economic projections, particularly for the eurozone). In working out its projections, the team was among the first on Wall Street to adopt the view that delta would have a minimal impact on the growth outlook for developed nations with high vaccination rates (though Goldman of course is not alone).

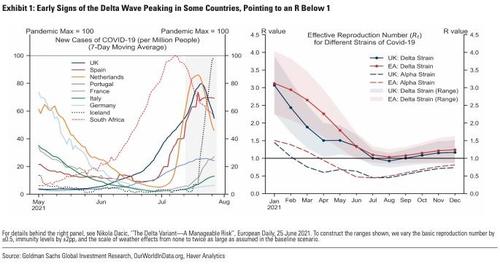

In its latest note, the Goldman team “stress-tested” its projections for the European economy (and by extension, the waning delta-driven wane) in Q&A format via a note to clients. The first example is also the most relevant: the team evaluates the evidence suggesting delta has “peaked” in Europe and the UK. The biggest risk factor according to the Goldman team is that the UK and Europe likely won’t reach the higher herd immunity threshold (between 80% and 85% vs. 70% in pre-delta times) needed to protect against delta. That could allow the virus’s reproduction rate to climb back above “1” later in the year (the demarcation point between spreading and slowing).

However “continued testing, some limits on mass events, and behavioural factors (e.g., voluntary mask wearing) could still lower R and help to contain rapid outbreaks,” the team wrote.

Here’s the rest of the Q&A courtesy of Goldman:

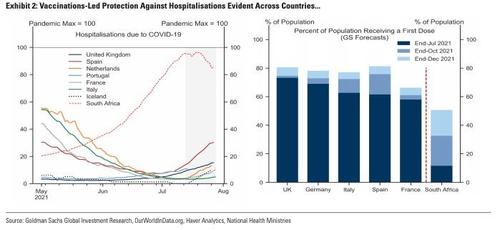

Q2. Has mass vaccination been a key factor in keeping hospitalisations relatively low in Europe?

A: Yes.

One of the most striking and consistent patterns in Europe over recent weeks has been the disproportionately low level of hospital admissions relative to new cases (Exhibit 2, left). Although hospitalisations have risen somewhat over recent weeks, the ratio of hospitalisations-to-infections has remained stable at record low levels. The available evidence overwhelmingly suggests a key role for vaccinations in explaining these dynamics. Across countries, this divergence is most pronounced across developed and emerging economies, with hospitalisations rising sharply in a number of low-vaccination emerging economies (including South Africa), as our Global Team has shown. By contrast, the relatively similar experience across European countries is consistent with comparably high levels of population that have been vaccinated (Exhibit 2, right).

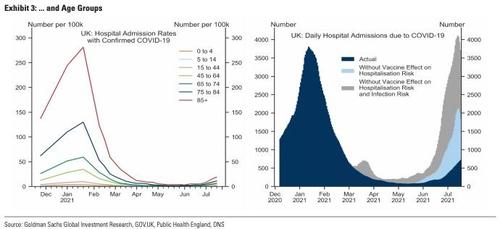

Within Europe, there is clear evidence of an effect of vaccinations on hospitalisation risk. For example, UK data shows a sharp reduction in rates of hospitalisations across age groups, with particularly large and frontloaded reductions for older age groups consistent with (i) higher pre-vaccine hospitalisation rates for these groups, and (ii) the prioritisation of older groups in the initial distribution of vaccines (Exhibit 3, left). Importantly, vaccines have had a twofold effect on observed hospitalisations: first, by lowering infection risk, and second, by lowering hospitalisation risk conditional on an infection (especially for the elderly). We can parse out the relative importance of these two effects by (i) taking as given the observed new infections across age groups, but assuming pre-vaccine hospitalisation probabilities across age groups, and (ii) allowing cases to evolve without the dampening effect of vaccines on infection risk. We implement (i) by using hospitalisation probabilities from late November last year, and (ii) by assuming the ratio of new cases for all age groups other than 0-14 years of age evolves in constant pre-vaccine proportions to new cases among the youngest (which have had the lowest vaccination rate). Our results suggest that overall hospitalisations would have already exceeded the January peak—when nearly 90% hospital beds in England were reportedly full—without the benefit from vaccinations in terms of lower infection and hospitalisation risks (Exhibit 3, right).

In Iceland, where over 85% of the 16+ population have received full doses—one of the highest shares globally—hospitalisations have only risen to around 10% of the historical peak, even though new cases have already reached an all-time peak after all restrictions on social contact were lifted at end-June. This pattern is also consistent with higher protection against hospitalisation than symptomatic infection, especially for non-mRNA vaccines (which have an overall share of around 43% in Iceland)—see ‘Efficacy of Vaccines Against Variants’ in our Tracker

Q3. Has there been a behavioural response from consumers to rising delta-variant cases?

A: Possibly some, but it appears modest so far.

Although hospitalisations have remained disproportionately low relative to cases, it appears likely that the renewed outbreaks may have prompted consumers to voluntarily adjust their behaviour to reduce exposure to a potential infection. Such adjustments could come with economic costs, for instance if consumers reduce their spending on consumer-facing service activities (such as retail or hospitality). To analyse the potential magnitude of these effects, we consider two approaches and focus on the UK where the ongoing delta wave has been most advanced in Europe.

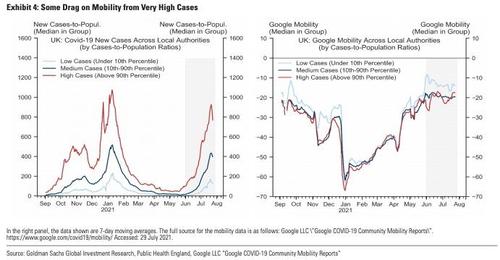

First, we make use of regional data on new infections and Google retail, transit, and workplace mobility for 152 local/regional authorities in the UK. We classify authorities on each date into three categories—’low’, ‘medium’, and ‘high’—based on new infections relative to local population size. Exhibit 4 (left) shows the median cases-to-population ratio for each category. We find that regions with lower case growth have typically seen higher mobility, although these differences were negligible during the spring nationwide lockdown (Exhibit 4, right).3 Over recent weeks, mobility has remained at higher levels in areas with lower cases, although the recent plateauing appears broad-based across all regions.

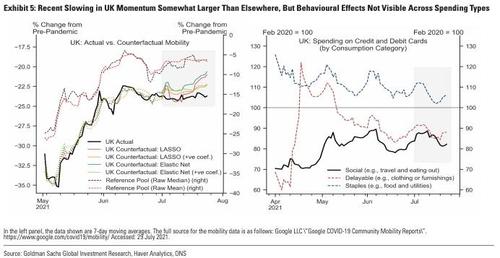

Second, to uncover whether the recent stagnation in some high-frequency UK metrics (including mobility) is UK-specific, we consider a set of 18 European countries which have not seen a significant increase in new cases since May—at least not large enough to potentially trigger a behavioural response—as a ‘counterfactual reference pool’ for the UK.4 We then use statistical methods to match UK’s actual mobility data using that from these countries between 1 May and 1 July (at which point the UK’s outbreak became more severe).5 Using the estimated coefficients, we then construct a counterfactual path for UK mobility after 1 July based on the mobility dynamics in the ‘low-delta’ reference pool, where the pace of mobility increases has also slowed in recent weeks. Our results nonetheless point to a moderate degree of UK underperformance relative to the counterfactual, suggesting scope for some behavioural effects (Exhibit 5, left).6 This appears consistent with the material downside surprise in the UK flash composite PMI for July.

We also look at high-frequency data on credit and debit card spending in the UK, which does not seem to indicate significant behavioural effects due to rising cases, as the recovery in household spending on ‘low-risk’ categories (such as staples) and ‘high-risk’ social categories (such as restaurants) has stagnated in tandem over recent weeks, albeit at different levels (Exhibit 5, right).

Overall, while we do find evidence of some UK underperformance relative to ‘low-infections’ countries since early July, the recent flattening of mobility data even in areas of the UK with low cases and for ‘low-contact’ types of spending suggests other possible reasons—such as a moderation in sentiment following an initial overshoot— may also be contributing to the recent slowing in UK high-frequency data. We expect this slowing to reverse given the further easing of restrictions since 19 July and now-moderating case growth.

Q4. Has the spread of the delta variant contributed to labour shortages?

A: Not in the Euro area (yet), and yes in the UK according to anecdotal evidence, but macroeconomic effects likely small and largely transient so far

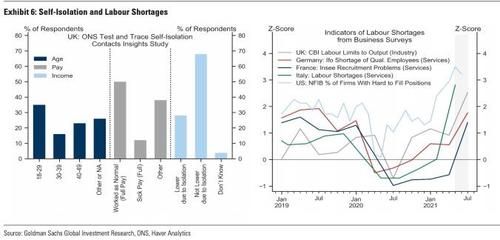

A large number of anecdotal reports from the UK over recent weeks have suggested significant labour shortages as a result of those infected or their close contacts being asked to self-isolate. Recent reports showed that around 520k people were ‘pinged’ by the NHS Test and Trace App in the week ending 18 July.7 Relatedly, the British Retail Consortium has reportedly warned that around 20% of shop workers have had to isolate. This was echoed in the weaker-than-expected flash PMIs for July, where ‘’shortages of labour availability were made worse as many staff self-isolated’

How significant are these effects for the macroeconomy? First, data from the UK suggests that the majority of those in self-isolation were under the age of 40 (with 35% aged 18-29), consistent with the skew in infections towards younger age groups (Exhibit 6, left). ONS survey data suggests less than 30% of those asked to self-isolate have reported some loss of income, and 50% of those employed pre-isolation still continued to work as normal. On one hand, the combination of (i) infections and self-isolations skewed toward younger age groups which have lower employment rates, (ii) continued fiscal support (e.g., via furlough/short-time work schemes), (iii) higher teleworkability than pre-pandemic, and (iv) plans to end self-isolation for double-vaccinated workers from mid-August, suggests the impact of widespread new infections and the ensuing rise in absenteeism from work may be smaller than headline figures could suggest (e.g., 520k people in self-isolation vs. 1.5m on furlough). On the other hand, the planned phase-out of fiscal support (e.g., furlough in the UK) and scope for continued upward pressure on cases could continue to disrupt labour supply and hamper the normalisation of activity.

The latest data from business surveys does suggest an increasing degree of labour shortages from previous quarters, but the cross-country data does not point to a clear difference between countries with higher cases (e.g., the UK and France) and those with lower cases (e.g., Germany and Italy) (Exhibit 6, right). With activity levels well-below normal (especially in services) and a large number of workers still under furlough/short-time work schemes, rising labour shortages could be a concern.8 While we do expect some upward pressure on unemployment rates in the UK and Euro area over coming quarters, we think the labour market consequences of the delta variant are likely to be largely transient, although some sectors (e.g., hospitality) could still be somewhat more affected temporarily.

Q5. Has the delta variant increased the risk of renewed restrictions over coming months?

A: Not significantly, and we think it poses a manageable risk overall.

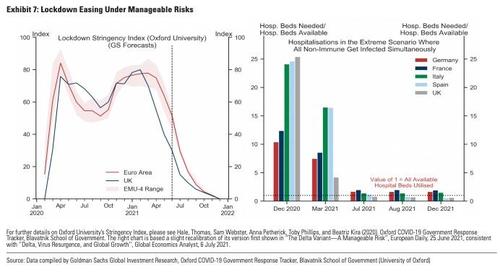

We continue to expect a gradual relaxation of the remaining containment measures by year-end, with Euro area governments in aggregate proceeding with some delay relative to the UK (Exhibit 7, left). We think the risk of renewed restrictions will ultimately depend on:

1. Cases: As we had argued above, we do see a risk of infections rising again in coming months, both in the UK and Euro area. That said, our analysis above points to limited evidence of significant persistent effects on consumer behaviour or labour availability from infections reaching levels we have seen in Europe over recent weeks. These effects could become larger if infections were to rise to much higher levels, in which case we would see scope for some targeted measures to be reimposed (e.g., limits on public gatherings or mass events, mask-wearing, or international travel), likely entailing only a modest economic cost.

2. Hospitalisations and/or fatalities: Our analysis suggests that even in a very severe and very unlikely scenario where each non-immune person was to become simultaneously infected, the pressure on hospitals would only modestly exceed available capacity.9 Modelled scenarios by the UK’s SAGE Institute also project hospitalisation outcomes that are well below (or no worse) than those from the winter wave, including in severe downside scenarios. We therefore think the risk of hospital overflow or elevated fatalities from here on is vastly lower than at any point since February 2020.

3. New variants: The potential emergence of new variants could take two forms. First, if a new highly-transmissive variant against which existing vaccines are nonetheless highly effective was to appear, its spread across Europe could cause some further delay to the recovery (depending on overall immunity levels at the point of its arrival). Second, if a new sufficiently-transmissive variant that is vaccine-resistant was to emerge, that could derail the recovery and remains the most severe downside risk in our view.

Ultimately, on our baseline, we think neither the potential upward pressure on cases nor a much more moderate increase in hospitalisations by year-end are likely to trigger economically meaningful renewed restrictions while more targeted, less economically-costly measures (such as those in the Netherlands or Iceland recently) are possible. Continued vaccine efficacy against all strains is a crucial element of our assessment.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 08/02/2021 – 18:00

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/37mTNXT Tyler Durden