Chicago Residents Fight To Reclaim Streets From Illicit Drug Dealings

Authored by Cara Ding via The Epoch Times,

Over the last four years, Patricia Carrillo and her husband Hugo Limon have done everything they could to steer drug sellers away from their block.

They took pictures of illicit drug dealings and shared them with police, they mustered the guts to meet with drug crew bosses, and they went to court to plead with judges to lock them up.

Their initiative annoyed some sellers, who threatened to harm them should they continue fighting, yet they did not back off.

Over time, neighbors began to pitch in, and things started to turn. Slowly, drug sellers dwindled in numbers and retreated to street corners.

“So many people told me that if I didn’t like it here, I should just move out. I was like, ‘No, this is my neighborhood, this is my home. Why should I move out, not those guys?’” Carrillo said.

Since Carrillo got married to Limon about 20 years ago, they have lived on the 1100 block of Monticello Avenue, in the West Humboldt Park neighborhood, on the West Side of Chicago.

The block used to be heavily African American. Now, eight out of ten residents are Hispanic.

Illicit drug dealings have always been an issue. At the worst point, sellers operated a drive-through right in front of their apartment, and Limon had to push his way through just to reach their gate.

When sellers concluded business for the day, they left behind garbage, urine, and feces. Occasionally, they left behind condoms, too.

There used to be a McDonald’s, a CVS store, and a Dunkin Donut store just around the corner, but one by one they closed or relocated.

“They were in the McDonald’s parking lot so customers could get meals and drugs at the same time. It was really really super bad,” Limon said.

But what bothered them most was that sellers consistently peddled weed to their two sons.

Their older son, Hugo Limon Jr., even got invitations to join the drug crew.

“It is obviously up to you if you want to be committed and addicted to that. If you choose to do that, then that is your fault, and that is you giving up essentially,” Limon Jr. said.

He said his parents helped him to tell right from wrong, but some of his friends were not so lucky. Their parents were mostly absent, or worse, abusive.

Six of his friends, all high schoolers, have joined gangs and sold drugs on the streets.

That is often a dead-end route, Limon Jr. said. He saw one of his friends shot multiple times after getting into an altercation with rival gang members.

For a long time, Carrillo and Limon had hoped the police would solve the problem. After all, by law, what these sellers were doing was illegal.

They called police at the 11th district station, attended community meetings to speak with beat officers, and they sent pictures of illicit drug dealings to a sergeant at the Narcotics Division.

But they said the answer they got was almost always, “Sorry, but there is nothing we can do.”

For these types of crimes, police must catch them in action, which was hard to do, they were told.

Or police could search a person based on reasonable suspicion that he has committed a crime—but many officers were wary of doing this for fear of potential civilian complaints or civil rights lawsuits, a police source told The Epoch Times.

A lot of times, police could only catch them with simple drug possession, not with the intent to distribute.

After all the hustles of arrest, paperwork, and jail booking, the cases would be quickly dismissed by prosecutors, or later tossed out by judges, police told them.

“Why bother doing all this if they will be out in hours?” police told them.

But Limon thinks there are still things that police can do better.

He said the local police station once detailed a squad car to the station near the drug spots, in the hope to deter illicit drug activities. But he often saw a police officer dozing off or looking at the phone in the car.

“Nobody put a gun to your head for you to choose this job. So if you are going to do this career, at least do your best,” Limon said.

The Chicago Police Department told The Epoch Times in a statement that they do not discuss specifics of policing, including deployment and patrol strategies, out of an abundance of safety and caution.

Out of options, Limon and several neighbors arranged a meeting with one of the drug crew bosses.

They told the boss, “Stay away from my property, stay away from my kids.”

The boss replied, “I don’t really care. I want to work my [expletive] off and I don’t care.”

The West Side of Chicago has long been a drug epicenter. Addicts from across the metro area drive via highway I-290 to its open drug markets to get fixes.

Then the boss asked, “What else do you want me to do?”

Limon and neighbors told him to clean up the place after his sellers left for the day. So for a while, the boss hired someone to clean up the block every day.

The boss also offered to pay $300 to rent a bouncy house for a block party, but Limon refused.

“If we accepted his money, he would think his sellers could stay here. So I said, ‘No, no, we don’t want your money, we want you to get out of here, and we are going to continue fighting’,” Limon said.

Some of the sellers got annoyed and told Limon to his face, “I know where you live. I know where your kids live. If you don’t stop, we are going to kill you.”

But Limon was undeterred. He said he talked to them just like a human being talks to another human being.

“They are people, though they are people doing really dumb things, and I don’t agree with it,” Limon said.

At the time, he was working two jobs, sometimes sleeping for only three hours a day. To help her husband, Carrillo gradually took over some work, including emailing pictures to police officers.

Carrillo, an immigrant from Mexico, spoke almost no English at the time. But the desire to better her block helped her overcome the language barrier and a shy character, she said.

n 2019, Carrillo was knocking on neighbors’ doors to get everyone on board.

“This is a bad neighborhood because we allow it. We need to stay together, we need to stay stronger,” Carrillo told them.

Some asked her to not bother them. Others told her, “This is West Side. What do you expect?”

Carrillo carried on.

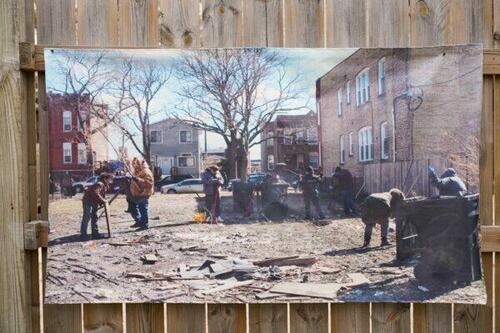

She led committed neighbors to clean up a vacant lot where sellers often hung around. They turned it into a community garden, with a mini basketball court, Mexican-style ground oven, and sitting areas.

She also led regular clean-up efforts, so the block was nice and neat; she held regular safety walks with police officers, so they knew what was happening on the block; and she talked to police captains, superintendent David Brown, and Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot.

Gradually, more and more neighbors pitched in.

“The sellers were like, ‘Okay, now I had the whole block against me,” Limon said.

Slowly, they dwindled in numbers, and retreated to street corners, according to Carrillo.

It was not clear if other factors were also responsible for the ebb and flow of illicit drug dealings on her block.

While Carrillo was making all these changes, another set of changes was also taking place in the criminal justice system.

In January 2020, Illinois legalized marijuana. Though it is still illegal to sell marijuana on the street without a license, the law further disincentivizes police to arrest weed peddlers, Limon said.

Soon the pandemic hit, court capacity dropped, and Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx temporarily halted prosecutions of low-level drug offenses. Foxx said by doing that her staff could focus more on violent crime.

Until this day, Foxx has not officially suspended that policy. In other jurisdictions, such as Baltimore, similar pandemic non-prosecution policies were later made permanent.

These changes reflect a wider trend in the criminal justice system to decriminalize drug possessions and divert people to social service programs. Common theories driving the trend are that drug arrests fail to address the root problems and disproportionately hurt black people.

A recent investigative piece by Chicago SunTimes and Better Government Association argues that drug arrests caused people to lose jobs, housing, and family ties; they also cost taxpayers millions.

But Limon asked, what about the cost to me and my family?

“Kim Foxx can go as far as she wants, but she doesn’t live here for 20 years. You can’t live here for 20 years and then you told me that you are going to go low on these guys,” Limon said.

Carrillo requested a meeting with Foxx but has not heard back from her office yet.

The Epoch Times did not receive a comment from Cook County State’s Attorneys’ Office by press time.

In recent months, Limon and Carrillo notice more sellers have moved back onto the corners of their block. The sellers also travel through their block more often. One night, Carrillo heard multiple rounds of shootings from her apartment.

Limon and Carrillo said they would not stop fighting. Recently, they became court advocates, going to court and talking to judges about the harm these sellers have caused to their neighborhoods.

First, they would get a list of cases from the Cook County State’s Attorneys’ Office. After that, they have a way to identify defendants who sold drugs on their block. Then, they attend related court hearings to plead with judges to lock them up or put them away longer.

“I said, ‘Look, judge, he got a gun case, he got a robbery, his rap sheet is so long, perhaps this time you should let him do some time,” he said.

But ultimately, it is up to judges to decide.

They also plan to ask judges to issue restraining orders against some sellers, essentially banning them from selling drugs on their block.

Some states’ attorneys warned Limon and Carrillo about coming to court. The defendants or their associates might retaliate against you or your family, they told the couple.

“I am not afraid,” Limon said.

“We are in the block fighting, and now we are in the court fighting.”

Tyler Durden

Wed, 04/20/2022 – 18:30

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/HmMBb54 Tyler Durden