Why Is Booz Allen Renting Us Back Our Own National Parks?

Authored by Matt Stoller via BIG,

“I Seen My Opportunities and I Took ’Em.” – George Washington Plunkitt of Tammany Hall

Two of the classic works of late 19th century American political literature, representing precisely opposite views of how commerce in an industrialized democracy ought to work, are Henry George’s Progress and Poverty, and the speeches of George Washington Plunkitt of Tammany Hall.

George was one of the great political economists of his day, and he ran and lost for mayor of New York City on an anti-monopoly and land reform ticket. George was interested in why we experienced tremendous inequality in the midst of great wealth, and traced it to the exploitation of land.

George was an international superstar, influencing both Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, as well as environmentalists and the modern libertarian movement. (There’s an iconic statue of the greatest mayor in Cleveland history, Tom Johnson, with Johnson holding a copy of Progress and Poverty.) The modern academic profession of economics arose in part as a reaction to the popular success of George’s work. The game Monopoly comes directly from George, and in many ways, the national parks, as well as everything from spectrum allocation to offshore oil drilling, must wrestle with Georgeist thinking.

But by land, he meant far more than just the plots upon which we live. “The term land,” George wrote, “necessarily includes, not merely the surface of the earth as distinguished from the water and the air, but the whole material universe outside of man himself, for it is only by having access to land, from which his very body is drawn, that man can come in contact with or use nature.” Unlike Marx, who saw the exploitation of capital over labor, George thought that the root of social disorder was a result of the power of the landowner over both capital and labor.

By land, he meant all value drawn purely from nature or from collective human existence. He would, for instance, consider ‘network effects’ a form of land, and likely seek regulation or national control of search engines. George had his first run-in with monopoly in San Francisco, where a telegraph monopolist destroyed his newspaper by denying him wire service. But his key work, in 1879, was written before the rise of the giant trusts, just as railroads, which were really land kingdoms, were becoming dominant.

A much more cynical set of works are the speeches of Plunkitt. Plunkitt was a political boss in New York City, a proud machine politician in office at the same time in the same political arena as George. Both men were interested in modern industry and wealth, and in both cases, the key fulcrum around which power flowed was not capital, but land. But while George sought a better world, Plunkitt just wanted to get rich, and saw in the purchase of land one of the key ways to do that.

Plunkitt’s key moral guidepost was the practical wielding of political power to enrich oneself. He posited something called “Honest Graft,” which he distinguished from crime in a formulation that every important corporate lobbyist, knowingly or not, has since used. To Plunkitt, stealing would be taking something that doesn’t belong to you. But if you happened to know that the city would need a piece of land, and you got there first, well, that was simply smart. As Plunkitt put it:

“I could get nothin’ at a bargain but a big piece of swamp, but I took it fast enough and held on to it. What turned out was just what I counted on. They couldn’t make the park complete without Plunkitt’s swamp, and they had to pay a good price for it. Anything dishonest in that?”

George was part of the land reform anti-monopoly school of Anglo-American thought, from Frederick Douglass to Thaddeus Stevens. Plunkitt was a machine politician, and proud of it. The battle between these two elements of America, the desire to conserve the public weal versus the desire to cynically plunder it, is still fierce today. It will probably never end.

And that brings me to the political conflict over our national parks, and the strange situation whereby a large government contractor, Booz Allen, somehow found itself in a position to rent us back our own land.

Every day, visitors to Vermilion Cliffs National Monument in Northern Arizona hike into an area named Coyote Buttes North to see one of the “most visually striking geologic sandstone formations in the world,” which is known as The Wave. On an ancient layer of sandstone, millions of years of water and wind erosion crafted 3,000-foot cliffs, weird red canyons that look like you are on the planet Mars, and giant formations that look like crashing waves made of rock. There are old carvings known as ‘petroglyphs’ on cliff walls, and even “dinosaur tracks embedded in the sediment.”

The Wave is unlike anywhere else on Earth. It is also part of a U.S. national park, and thus technically, it’s open to anyone. Yet, to preserve its natural beauty, the Bureau of Land Management lets just 64 people daily visit the area. Snagging one of these slots is an accomplishment, a ticket into The Wave is known as “The Hardest Permit to Get in the USA” by Outside and Backpacker Magazines.

To apply requires going to Recreation.gov, the site set up to manage national parks, public cultural landmarks, and public lands, and paying $9 for a “Lottery Application Fee.” If you win, you get a permit, and pay a recreation fee of $7. The success rate for the lottery is between 4-10%, and some people spend upwards of $500 before securing an actual permit.

But while the recreation fee of $7 goes to maintaining the park – which is what Henry George would appreciate – the money for the “Lottery Application Fee” is pure Plunkitt. That money goes to the giant D.C. consulting firm, Booz Allen and Company. In fact, since 2017, more and more of America’s public lands – over 4,200 facilities and 113,000 individual sites across the country at last count – have been added to the Recreation.gov database and website run by Booz Allen, which in turn captures various fees that Americans pay to visit their national heritage.

You can do a lot at Recreation.gov. You can sign up for a pass to cut down a Christmas tree on the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests, get permits to fly-fishing, rifle hunting or target practice at thousands of sites, or even secure a tour at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. There are dozens of lotteries to enter for different parks and lands that are hard to access. And all of them come with service fees attached, fees that go directly to Booz Allen, which built Recreation.gov. The deeper you go, the more interesting the gatekeeping. As one angry writer found out after waiting on hold and being transferred multiple times, the answer is that Booz Allen “actually sets the Recreation.gov fees for themselves.”

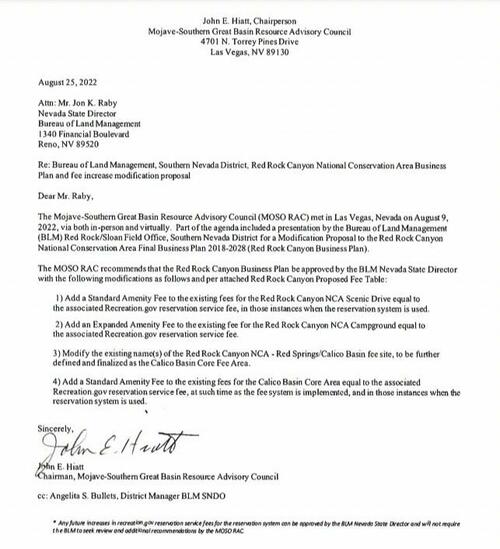

Lately, hundreds of sites have begun requiring the use of the site. A typical example is Red Rock Canyon, which added “timed entry permit” in the past two years. Such parks, before adding these new processes, usually do a “trial” period followed by a public comment period, and then the fees are approved by a Resource Advisory Council, objects of derision composed of people appointed by the government bureaus. As one person involved in the process told me, these councils are sort of ridiculous. “Agencies fill it with people beholden to them,” he said. “so the council playing committee rubber stamps whatever they send their way, often even if it makes no sense.”

The entry permit almost always become permanent. This includes heavily visited lands like Acadia National Park (4 million annual visitors), Arches National Park (1.5 million), Glacier National Park (3 million), Rocky Mountain National Park (4.4 million), and Yosemite (3.3 million). There’s nothing wrong with charging a fee for the use of a national park, as long as that fee is necessary for the upkeep and is used to maintain the public resource.

That was in fact the point of the law passed in 2004 – the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act – to give permanent authority to government agencies to charge fees for the use of public lands. But what Booz Allen is doing is different. The incentives are creating the same dynamics for public lands that we see with junk fees across the economy. Just as airlines are charging for carry-on bags and hotels are forcing people to pay ‘resort fees,’ some national parks are now requiring reservations with fees attached. And as scalpers automatically grabbed Taylor Swift tickets from Ticketmaster using high-speed automated programs, there are now bots booking campsites.

None of this is criminal, though the fee structure may not be lawful, but it is very George Washington Plunkitt. “I Seen My Opportunities,” he said, “and I Took ’Em.”

Honest Graft

The entry point for Booz Allen can be traced back to the Obama administration, and a giant failed IT project. In 2010, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act, pledging that by 2014, the government would have a website up in which uninsured Americans could buy health insurance with various subsidies. In perhaps one of the most embarrassing moments of the Obama administration, Healthcare.gov failed to launch the day the new health law came into force, and millions couldn’t sign up to take advantage of it.

It’s hard to overstate the shame of that moment. The government had spent $400 million over four years – more time than it took the U.S. to enter and win World War II – and yet, the dozens of contractors couldn’t set up a website to take sign-ups. The whole thing was an embarrassing disaster, a festival of incompetence and greed. (Despite the failure, the main IT contractor’s CEO became a billionaire. Honest graft indeed.)

President Obama hired Google’s Mike Dickerson to come in and fix the Healthcare.gov website, which Dickerson and his team did. This wasn’t some miracle, it’s not like websites were new technology. The government itself created the internet and most of the underpinnings of digital technology, and it had many functional and important systems. But the Google name at that point was magic, and so the U.S. Digital Service, designed to help the government use technology, was born. After Dickerson, the new head was Google’s Matt Cutts, and then health care monopolist Optum’s Mina Hsiang. The U.S. Digital Service, far from being particularly competent, is a branding exercise. It is full of people from Amazon and Google, and tends to push the government to outsource its technology to third party contractors.

Following the U.S. Digital Service’s playbook is what led the government to bid out and allow the creation of Recreation.gov, with its weird and corrupt fee structure. In 2017, Booz Allen got a 10-year $182 million contract to consolidate all booking for public lands and waters, with 13 separate agencies participating, from the Bureau of Land Management to the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration to the National Park Service to the Smithsonian Institution to the Tennessee Valley Authority to the US Forest Service.

The funding structure of the site is exactly what George Washington Plunkitt would design. Though there’s a ten year contract with significant financial outlays, Booz Allen says the project was built “at no cost to the federal government.” In the contractor’s words, “the unique contractual agreement is a transaction-based fee model that lets the government and Booz Allen share in risk, reward, results, and impact.” In other words, Booz Allen gets to keep the fees charged to users who want access to national parks. Part of the deal was that Booz Allen would get the right to negotiate fees to third party sites that want access to data on Federal lands.

It’s a bit hard to tell how much Booz Allen was paid to set up the site. Documents suggest the firm received a lot of money to do so, but it’s also possible that total amount was the anticipated financial return. I wrote to Recreation.gov team leader Julie McPherson at Booz Allen to find out what they were paid to build the site, and I haven’t heard back. Regardless, there’s a lot of money involved. For instance, as one camper noted, in just one lottery to hike Mount Whitney, more than 16,000 people applied, and only a third got in. Yet everyone paid the $6 registration fee, which means the gross income for that single location is over $100,000. There’s nothing criminal about this scheme, but it is a form of Honest Graft, or of handing a Ticketmaster-like firm control of our national parks.

Judgment Day

In 2020, an avid hiker named Thomas Kotab sued the Bureau of Land Management over the $2 “processing fee it charges to access the mandatory online reservation system to visit the Red Rock Canyon Conservation Area.” He claimed, among other things, that the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act mandated that this fee was unlawful, because it had not gone through the notice-and-comment period required by the act. Kotab, an electrical engineer by training, is one of those ass-kickers in America, who just goes after a grift because, well, it’s just wrong.

A few years later, a judge named Jennifer A. Dorsey, appointed by Obama in 2013, agreed with him. She looked at the statute and found that Congress authorized the charging of recreation fees for the purpose of taking care and using Federal lands, not administrative fees that compensated third parties. As such, Booz Allen’s ability to set its own prices was inconsistent with the law mandating the public’s right to comment on what we are charged for using our own land.

The BLM sought to appeal, but then dropped it in July. Rather than a bitter procedural argument about classifying fees, the government and Booz Allen have decided they’ll just go through the annoying process of having the public comment on Booz Allen’s compensation, and then ignore us using their phony advisory council process. Here, for instance, is the Mojave-Southern Great Basin Resource Advisory Council Meeting in August simply proposing to substitute new standard amenity fees “equal to the associated Recreation.gov reservation service fee.”

One notable part of this saga is that technically, the BLM and Booz Allen owe refunds to everyone who went through Red Rock Canyon’s timed entry system from 2020-2022, but they’ll probably ignore that and steal the money. That verges into actual graft from the ‘honest’ type, but I suspect Plunkitt did that as well from time to time.

And yet, it’s not over. The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act authorization runs out in October of 2023, which means that Congress has to renew it. Hopefully, an interested member of Congress who loves Federal lands could actually tighten the definitions here, and find a way to stop Booz Allen and these 13 government agencies from engaging in this minor theft via junk fees. It wouldn’t be hard, and it would be fun to force a bunch of government agencies to actually do their job and either take over the site themselves or pay Booz Allen a fee for its service. (Another path would be Joe Biden, through his anti-junk fee initiative, simply asserting through the White House Competition Council to the 13 different agencies that they end Booz Allen’s practice of charging these kinds of fees.)

It’s easy enough to see scams everywhere, and here is certainly one of them. But let’s not lose sight of the broader point. Henry George, at least in this fight, has won. Yes, Booz Allen gets to steal some pennies, but we have a remarkable system of public lands and waters that are broadly available for all of us to use on a relatively equal basis. And we can still see the power of George-ism in the advocacy of hikers and in the intense view that members of Congress had when they passed the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act in 2004, which strictly regulated fees that Americans would have to pay to access our Federal lands. Indeed, the anger and revulsion I felt at the fees Booz Allen puts forward comes from George, even if I didn’t necessarily trace it there at first.

We are in a moment of institutional corruption, but these moments are transitory as institutions change. George Washington Plunkitt, and his political descendants at Booz Allen, might have gotten rich, but Henry George imparted instincts to Americans that are far more permanent.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 12/01/2022 – 22:15

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/maSU6Wv Tyler Durden