The Metaverse Was A Pandemic Pipe Dream

Submitted by Jack Raines via Young Money,

In the opening chapter of The Reality Bug, the fourth novel in the Pendragon fantasy series, protagonist Bobby Pendragon finds himself walking through Rubic City, a metropolis in the foreign world of Veelox. Rubic City is similar to the cities in Bobby’s native Earth, with paved streets and towering skyscrapers, but there is one striking difference: there aren’t any people. Rubic City resembles a post-apocalyptic Manhattan where society has disappeared but its constructs remain.

Bobby eventually crosses paths with a local, Aja, who explains that the planet isn’t empty, but most of its population have opted to spend their time in a digital world called Lifelight, which is housed in a large metallic pyramid overlooking the city.

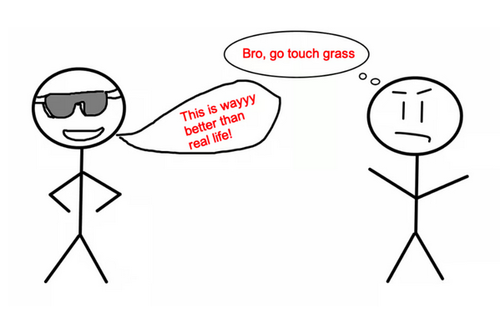

Lifelight is an immersive virtual reality program that brings one’s deepest desires to life, and the experience is so enthralling that few of its users wanted to return to the physical world after their first taste of this new euphoria.

When Bobby arrived, 99% of Veelox’s citizens were spending every waking hour in Lifelight, and the remaining outsiders all worked as computer engineers maintaining the virtual world and physical caretakers looking after participants’ bodies.

While millions of people were lost in their own digital wonderlands, the real world around them was slowly rotting away.

As the pandemic raged two years ago, the term “Metaverse” went mainstream, conjuring dystopian images of Lifelight and various Black Mirror episodes in my mind.

The hype exploded in October 2021 when one of the world’s tech giants, the company formerly known as “Facebook,” opted to change its name to “Meta,” signaling the entry of a new digital age.

Suddenly, every company faced a decision: launch a Metaverse division or risk being left behind. Mark Zuckerberg invested billions into his company’s “Horizon Worlds,” a virtual reality designed for communal meet-ups. Nike built Nikeland on Roblox’s platform to let fans meet, socialize, and take part in a wide array of brand experiences. And of course, the “Metaverse” became intertwined with “Web3” when platforms like Decentraland launched, allowing users to buy digital plots of land as NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain.

Respected banks like JPMorgan Chase published 17-page research memos breaking down “Metanomics” for curious investors, athletes changed their profile pictures to $100k JPEGs of monkeys, venture capital firms launched $600M funds to invest in the Metaverse, and corporate brand Twitter accounts began communicating in the cringe-heavy jargon of Web3:

it seemed inevitable that the future of the world would be spent playing virtual reality tennis in the Wii Sports Resorts with our eight billion closest friends… until one day, the funniest thing happened: no one cared about the Metaverse anymore.

Daily active users on Sandbox and Decentraland, two Metaverse platforms both valued at $1B+, peaked at 4,503 and 675 individuals respectively before declining to 522 and 38 in October 2022.

Meta’s Horizon Worlds boasted 300,000 monthly users in February 2022, and company management projected 500,000+ users by the end of the year. Just eight months later, monthly usage fell below 200,000 users as most visitors didn’t return after their first month.

Of course, it’s hard to blame users for not returning when Meta’s own VP of Metaverse had to beg his own employees to spend more time in Horizon Worlds, saying in an internal memo, “For many of us, we don’t spend that much time in Horizon and our dogfooding dashboards show this pretty clearly. Why is that? Why don’t we love the product we’ve built so much that we use it all the time? The simple truth is, if we don’t love it, how can we expect our users to love it?”

And now, as company after company shuts down their Metaverse divisions, I believe this digital experiment is on its last legs.

I, for one, am glad that the dystopian Metaverse from Bobby Pendragon’s adventures failed to become a reality, but this whole experiment raises an important question: How did “the Metaverse” become such a large phenomenon in the first place?

I have some thoughts:

1) Extrapolating one-off scenarios is a dangerous game.

Much of the world spent the greater part of two years locked in the confines of their homes, so it’s no surprise that web activity saw a significant uptick during the pandemic.

However, this Metaverse-centric environment wasn’t some permanent evolution of the human condition, it was the response to a once-in-a-century tail risk, Covid-19. And sooner or later, that risk was going to be mitigated.

The Lindy Effect states that the future life expectancy of some non-perishable thing, such as a technology or idea, is proportional to its current age. Basically, stuff that has been around for a while will continue to be around for a while.

Taking a stroll through the city with friends and family on a nice summer day is Lindy.

Attending concerts and live sporting events is Lindy.

Crushing cold ones with the boys is Lindy.

Seriously, the ancient Sumerians created a hymn to their goddess of beer in the 18th century BC (!!!), giving us this all-time line: “He who does not know beer does not know what is good.” Crushing cold ones with the boys is a 4,000-year-old tradition.

Do you know what isn’t Lindy? Watching a digital Travis Scott concert in Fortnite. It really shouldn’t be a surprise that real-life socialization quickly rebounded once pandemic measures were lifted.

The thing is, when a temporary shift in consumer trends provides tailwinds for your business or idea, it is natural to hope that this aberration becomes a permanent change. But we live in a mean-reverting world, and bold projections that ignore mean-reversion rarely work out.

2) You can spend a lot of money on really dumb stuff when cash reserves are sitting at all-time highs and interest rates have collapsed to all-time lows.

Burning $36B to remake a worse version of The Sims sounds stupid until you realize that the alternative is throwing your cash at T-Bills that pay nothing while inflation is 8%.

When fixed-income assets don’t generate yield and investors have trillions of dollars that need to be deployed, they are going to deploy somewhere, and insane valuations for ridiculous long-shot bets begin to look a lot more rational.

At different times, I have jokingly said that several things were low-interest rate phenomena, but there is some truth to that idea. It’s not that low-interest rates somehow create outlandish ideas, but the pursuit of yield in the face of few investment options can send a lot of capital to the outer realms of rationality.

The problem, of course, was the assumption that T-Bills would always pay nothing and cash reserves would always be abundant. Snap back to reality, ope, there goes gravity.

3) Institutions are susceptible to FOMO too.

Would JPMorgan have published a research memo on the economics of the Metaverse and the value propositions offered by tokenized digital real estate in 2019? Of course not. Half of the words in the previous sentence didn’t even exist in 2019.

But 2022 was a different story.

Whether you’re an insecure college freshman considering a pair of New Balances to fit in on Greek Row or a billion-dollar institution considering adding bitcoin to its balance sheet as an “inflation hedge,” the temptation to follow the crowd grows damn-near irresistible as more and more of your peers adopt a trend.

Self-doubt increases and logic goes out the window as you think, “Well, I don’t understand this idea, but if everyone else must see something I don’t. Maybe we should get involved too.”

And that’s how a $377B bank ends up sponsoring a lounge in a Metaverse world that resembles Minecraft if you played it on your toaster oven.

Rest in pieces to the Metaverse, it was fun while it lasted. I guess.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 04/28/2023 – 09:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/49UL20k Tyler Durden