Authored by Bob Ivry via RealClearInvestigations,

Paul Fishbein’s conviction on rent fraud charges in New York City last year was a feast for the tabloids.

The story was crazy enough to get readers to click. Prosecutors said that Fishbein, 51, somehow convinced local housing agencies that he owned dilapidated apartment buildings that he didn’t, enabling him to move in tenants and skim government rent subsidies meant for lower-income, disabled, and elderly residents. Fishbein kept the con going for more than years. His take: $1.8 million.

In February, a judge handed Fishbein 70 months in prison and ordered him to pay back roughly double what he’d taken. The case was a win for city investigators and federal prosecutors. But one agency was conspicuously absent from the celebration: the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, a source of the taxpayer money that Fishbein stole. HUD had nothing to do with bringing to justice the fraudster who’d made off with its cash. It was an indictment of the agency’s decade-long resistance to fighting fraud — and a portent for any promise to tame the bureaucratic state, like the kind touted for a second Trump administration.

HUD’s lack of involvement in the Fishbein case isn’t necessarily a reflection on field investigators from the agency’s Office of Inspector General, a nationwide force of 140 sleuths who carry guns and badges and are armed with subpoena power. After all, also in February, HUD OIG investigators participated in a massive dragnet that busted 70 current and former New York City Housing Agency employees for soliciting bribes. HUD’s absence from the Fishbein affair was more a result of the agency’s inability to properly track rental-assistance money that, because of error or fraud, ends up in the wrong places — what the government calls improper payments.

HUD, like other agencies responsible for spending taxpayer money, is required to estimate improper payments and post the results. Auditing themselves in such a way is a sign that at least the agencies are following the money, even if a portion of it is lost to waste or crime. Most agencies are able to complete the task, but not HUD, which blames the failures on various snafus, both human and technological, and says the earliest it can start properly keeping tabs on the money is 2027, “dependent on funding.”

HUD’s internal watchdog has already spent the past 10 years hectoring the agency to improve its fraud detection. Fiscal 2023, which ended Sept. 30, marks the seventh consecutive year that HUD failed to report improper-payment estimates and the 11th year in a row that the inspector general found that HUD was not in compliance with improper-payment laws. Without changes, HUD Inspector General Rae Oliver Davis told the Cabinet Department in a January management alert, “HUD may miss opportunities to identify and eliminate fraud vulnerabilities, leaving its funds and reputation at risk.”

That’s the watchdog’s gently diplomatic way of telling HUD to get its act together already. The lack of accountability spans the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations. There’s little doubt that it can be tough to track taxpayer money once it’s sent out into the world: HUD’s flows through 3,700 local housing authorities and countless landlords on its way to putting a roof over some 3 million American households. But those complications are also a convenient scapegoat for HUD, as is the lag in upgrading technology systems that could make the accounting job easier.

Meanwhile, we’re talking about two rental assistance programs, which together constitute 68% of HUD’s annual budget. The programs’ combined fiscal budget for 2025, which starts Oct. 1, is slated to be $49.5 billion. Because the numbers are so high, undetected criminality can cause taxpayer losses in the multiple millions.

“Action is needed immediately,” Davis wrote in a January management alert addressed to acting HUD Secretary Adrianne Todman.

One Bright Spot

There was one bright spot in the sometimes contentious relationship between HUD and its Office of Inspector General. Last month, HUD agreed to use a risk-management plan for fraud that the agency watchdog had put together during the COVID-19 pandemic. The inspector general said the move would improve monitoring in one of the two big rental assistance programs, laying the groundwork for improved fraud prevention.

Congress created the two HUD programs – Project-Based Rental Assistance and Tenant-Based Rental Assistance – in an effort to stem homelessness. The $16.7 billion PBRA helps house 1.2 million lower-income families. About 49% of the households that receive PBRA are headed by an elderly person and 16% by the disabled. One-quarter of the recipients are families with children. The assistance is attached to certain rentals; an eligible tenant must live in a specific apartment to receive help. That contrasts with the $32.8 billion TBRA, which provides aid that follows a tenant from home to home. Both programs are administered by local housing agencies, whose cooperation with the federal government in tallying up payment errors sometimes lacks enthusiasm.

Even though the law directs federal spending programs to estimate their improper payments, PBRA and TBRA aren’t the only ones that fail to do so. Among the transgressors are the Agriculture Department’s $111 billion Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, which skipped filing estimates in 2015, 2016, 2020, and 2021, and the Department of Health and Human Services’ $31 billion TANF, or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families. Both SNAP and TANF have blamed snags on a lack of coordination with the state and local agencies that manage the programs.

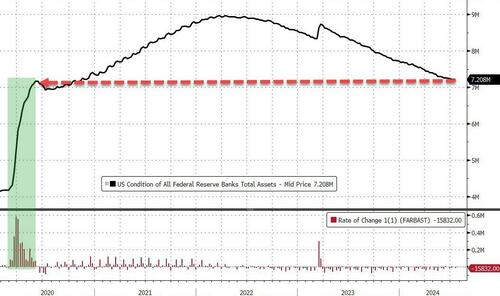

For fiscal 2023, improper payments across the entire government amounted to $236 billion, according to the Government Accountability Office, which compiles agencies’ estimates. While that number is the only one we have, it’s not accurate. The GAO said that it received a full accounting from only 14 of the 24 departments required to report. Historical numbers come with the same flaw. Since 2003, cumulative estimates of improper payments by executive branch agencies have reached $2.7 trillion, the GAO said. Even though that figure is low, because it’s missing numbers that agencies failed to report, it’s still equivalent to about 10% of America’s Gross Domestic Product.

Despite its failures in reporting improper payments, “HUD has oversight and monitoring in place to ensure the integrity of its rental-assistance programs,” an agency spokesperson said in an email statement.

The spokesperson said that local housing agencies and not HUD are responsible for determining whether tenants are eligible for the programs and how much assistance they qualify for, with HUD providing oversight directly or through the local housing agencies.

By reviewing compliance reports and audited financial statements, HUD is able “to ensure that improper payments are minimized and instances of non-compliance are identified and addressed,” the spokesperson said in the email. “In addition, HUD has requested more funding for system enhancements to modernize and improve HUD technology systems to support our oversight efforts.”

Artificial intelligence might help HUD identify fraudsters such as Fishbein before his swindle can reach its seventh birthday, but as the HUD spokesperson said, that takes money. The Biden administration kept the agency’s budget steady at $72.1 billion from 2023 to 2024. Its proposed fiscal 2025 budget of $72.6 billion is a 0.6% bump.

Joel Griffith said he knows where to find the money for expanding HUD’s computer-based fraud detection: the agency’s environmental programs. Griffith, a research fellow specializing in financial regulations for the Heritage Foundation, the conservative think tank responsible for Project 2025, recommends taking the $250 million earmarked for “climate resilience and energy efficiency” in HUD’s latest budget and spending it instead on upgrading information technology. Add the agency’s green retrofitting project – as much as $50,000 for each targeted housing unit – and that should add up to enough for HUD to prevent, rather than chase, a lot of rental-assistance fraud, he said.

‘Beef Up Enforcement’

Donald Trump slashed the budget of HUD’s inspector general by 3.6% in 2021, the last year of his budget oversight, while President Joe Biden proposes hiking it by 10% for 2025. Regardless, Griffith urged the next president, “whoever he is,” to “beef up enforcement.”

“Prevent fraud by prosecuting bad actors and publicizing it,” Griffith said. “Enforcing the law is a responsible use of taxpayer resources.”

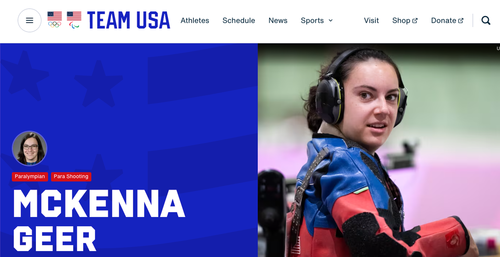

Though HUD’s Inspector General’s office may have missed out on the publicity surrounding the splashy Fishbein conviction, they’ve been busy. They helped lay the groundwork in Georgia for an October conviction of a Milledgeville Housing Authority payroll clerk who admitted she paid herself $575,014 more than she was entitled; helped secure a guilty plea from a San Francisco man who received $341,455 in fraudulent payments for a residence that turned out to be worth $2.4 million; and saw convictions on bribery and fraud charges of four Pennsylvania men, including the director of the Chester Housing Authority and his chief assistant.

If those cases seem a tad small-fry for investigators hunting for misdeeds in the stereotypically shady rental industry – especially when solutions to systemic problems are called for – there’s the February arrest of 70 former and current New York City Housing Authority employees for bribery and solicitation of bribery. Prosecutors said the administrators pocketed a collective $2 million over 10 years in pay-for-play schemes to hand out work contracts at HUD-funded properties. The Department of Justice called it “the largest number of federal bribery charges on a single day in DOJ history.”

Though the arrests gave the tabloids an opportunity for a thorough public shaming of the accused – and were another example that there’s big money in poverty – they might have also pointed to a bigger issue: a possible reason why it’s been so difficult, at least in New York, for HUD to estimate improper payments.